64

The Cartographic Panorama

H. C. Berann

Heinrich Caesar Berann, the father of the modern cartographic panorama, was born 31 Mar 1915 in Innsbruck, Tyrol, Austria. Although his family included established painters and sculptors, his father never supported his interest in fine art, so he learned to paint on his own. As a teenager he studied graphic design at the Bundeslehranstalt für Malerei in Innsbruck and, after graduating in 1933, began a career as a poster designer. The next year he won a competition for a panoramic map of the newly opened Großglockner Hochalpenstraße mountain pass.

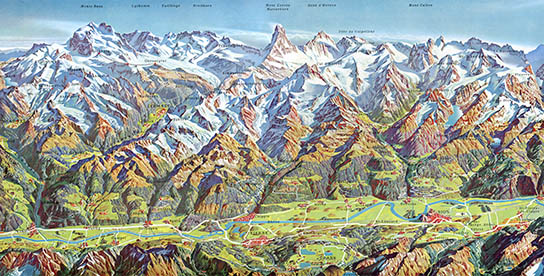

Not surprisingly, his work caught the attention of the bourgeoning Tyrollean tourist industry and soon other resorts were commissioning panoramas; and not just those in Tyrol, but throughout the Austrian, German, French and Swiss Alps.

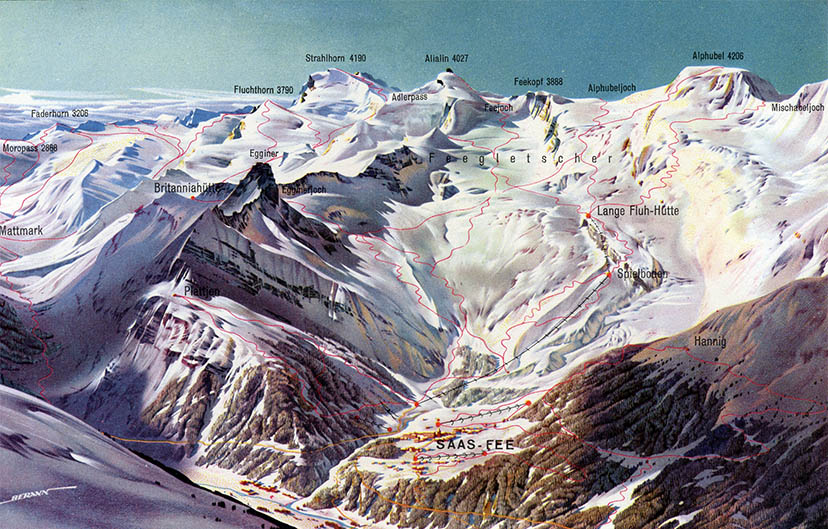

Kleinwalsertal, Tyrol, 1954

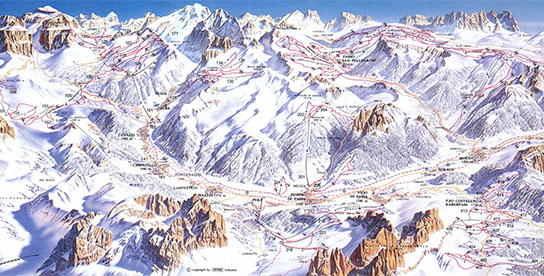

Val di Fassa, Trento, date unknown

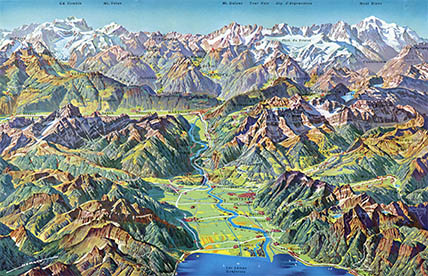

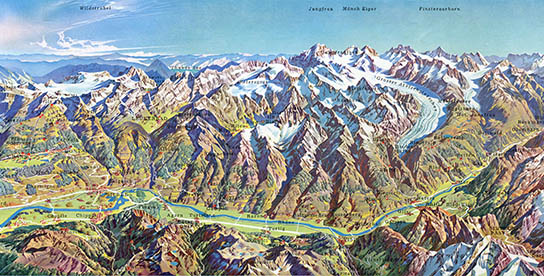

In 1952 he opened a studio in Lans, near Innsbruck, and for the next 50 years split his interest between fine art and commercial panorama. Over time his tourist panoramas became more detailed, cartographic and much larger in scope. Consider these paintings covering the the entire Swiss canton of Wallis (or Valais):

Wallis, Lac Léman to Martigny, ca.1961

Detail, Wallis, Sion to Furkapass, ca.1961

Detail, Wallis, southern side, ca.1961. You really need to click the image for the scope of the panorama

His large body of commercial tourist work lead him to design the official map for the 1956 Cortina Winter Games2 which, in turn, lead to a series of commissions for the National Geographic Society starting in 1963 with an Everest and Kimbu-Himal panorama.

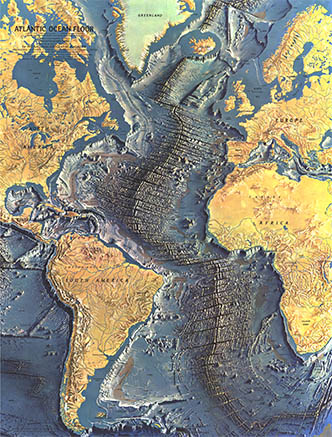

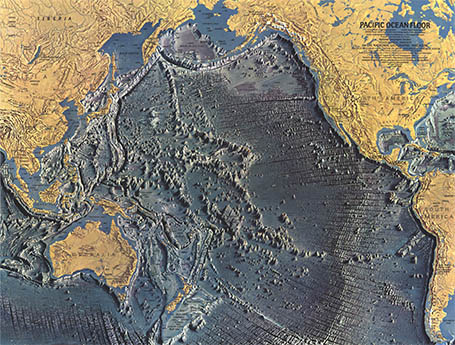

In 1967 Berann painted the first in a series of plan oblique physiographic maps of the ocean floor for Marie Tharp and Bruce Heezan and their collaboration culminated in the 1977 World Ocean Floor map. The spectacular 1977 map revolutionized the theories of plate tectonics and continental drift. Lawrence, writing for Mercator’s World, called it “possibly the closest thing Earth science has to iconography:” 3,4

Atlantic Ocean Floor, Jun 1968

Pacific Ocean Floor, Oct 1969

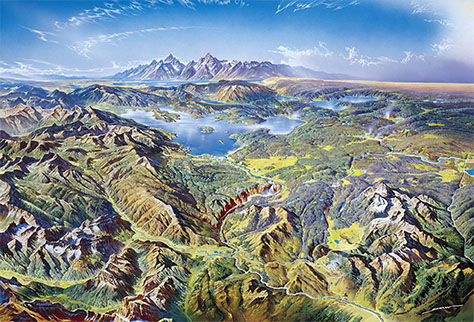

Berann continued his commercial panorama work, painted large-scale plan oblique maps for Mairs Geographischen Verlag, among others, and in 1986 began his last major cartography project – a series of panoramas for the U.S. National Park Service. Berann’s gauche and tempera panoramas, which relied on topographical map and aerial photographs, took as much as several years to complete. They show an artist at the end of his career, but in total command of both his cartography and art: 5

North Cascades, ca.1987

Yellowstone, ca.1989

Yosemite, ca.1991

Denali, ca.1994

Berann retired from commercial and cartographic work after his Denali panorama. He spent his last five years devoted to fine art.

To be fair to the hard-core cartographer, Berann never had any formal cartographic training and took artistic liberties with his work. He routinely exaggerated vertical scales, widened valleys and even rotated mountain peaks to show landmarks of interest. He also employed a decidedly non map-like palette of nearly primary colors. But it is precisely these qualities that you can’t replicate by computer 3D plotting of a data set.

1. For more information about Berann see The World of H. C. Berann, maintained by his grandson, Matthias Troyer. The site includes, among other things, a complete concordance of his panoramas.

2. Between 1956–1998 he painted a panorama of the Winter Olympic venue for six out of 11 Olympics. He even prepared maps for some candidate cities.

3. Lawrence, D. Mountains under the sea: Marie Tharp’s maps of the ocean floor shed light on the theory of continental drift. Mercator’s World.1999; 4(6): 36–43.

4. For more information on Berann’s plane oblique releifs see: Jenny, B, Patterson, T. Introducing Plan Oblique Relief. Cartographic Perspectives. 2007 Spring;57: 21–40. Which is available online at shadedrelief.com (not to be confused with the equally wonderful reliefshading.com).

5. For an excellent paper about Berann and his National Park Service commissions see: Patterson, T. A View from on High: Heinrich Berann’s Panoramas and Landscape Visualization Techniques for the U.S. National Park Service. Cartographic Perspectives. 2000 Spring; 36. The paper and many high-res images are online at shadedrelief.com.

1 May 2010 ‧ Cartography