The Box of Vacations

The Story of William

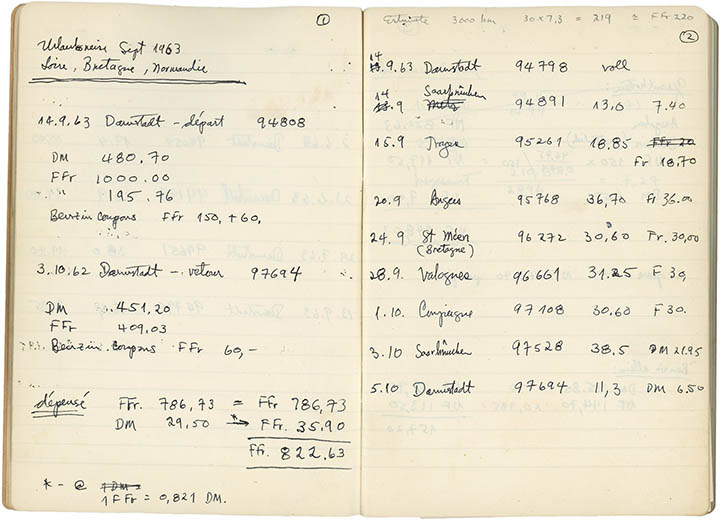

One of the most interesting things in the Box of Vacations was a notebook that William had bought from Karl Weiss, a stationer near the University of Darmstadt, where he worked. He used the notebook to record—in German, French and occasionally English—his car expenses, including the location, odometer reading, amount and cost of each fill up. He even calculated that it cost 3.9 pfennigs/ kilometer in gas to drive his car to Switzerland and noted that it cost 79.45 francs to replace his battery in France. William, if nothing else, was rather quantitative.

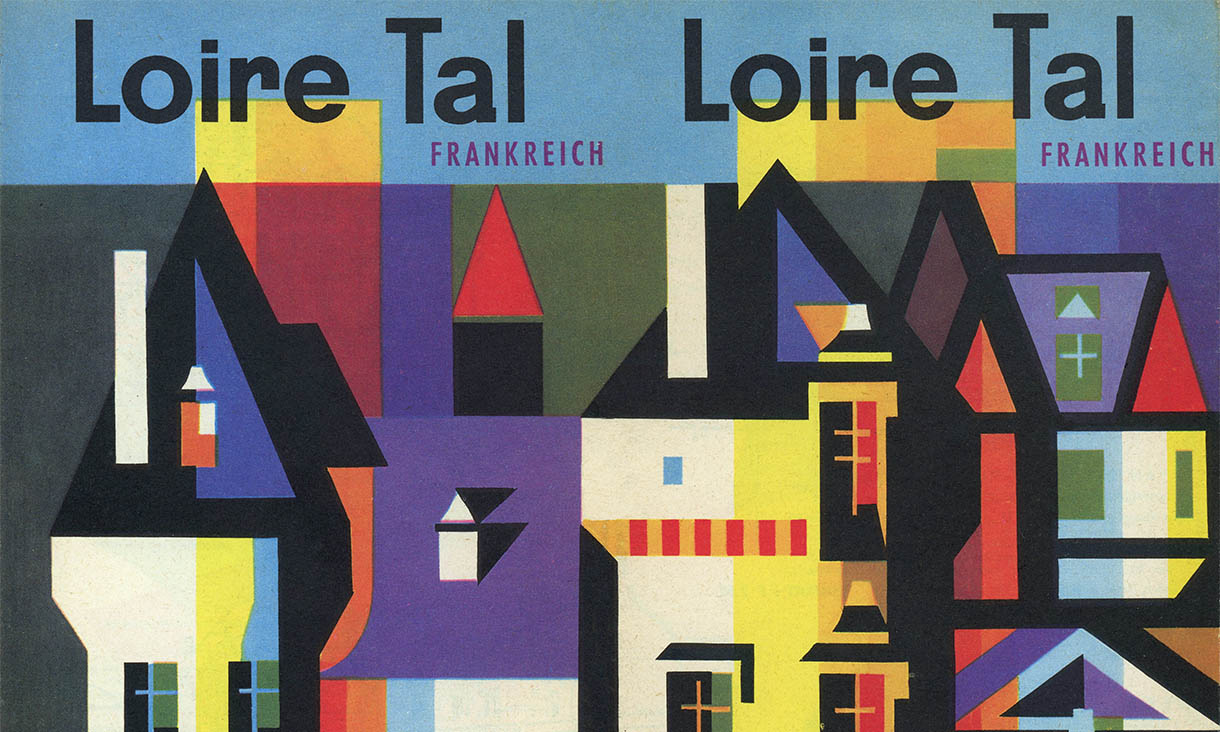

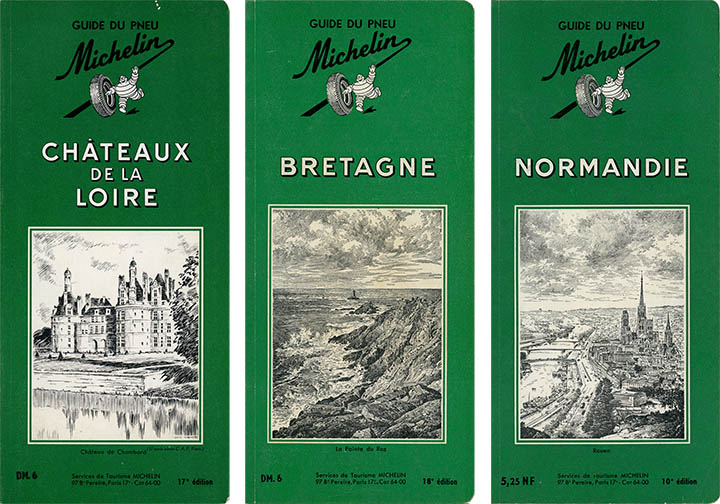

According to his notebook entries as well as a stack of stapled receipts, William took a trip through northern France in September, 1963. He departed from Darmstadt on the 9th with a full tank of gas, a 1000 French francs and another 210 francs worth of benzin coupons and stopped the first night in Saarbrucken, on the German–French border. He spent the next several days driving across the French countryside—past dairy farms and potato fields, then vineyards, barley and wheat fields. Along the way he visited the Meuse-Argonne Cemetery (the largest American war cemetery in Europe) and by the 15th had made it to Chateauneuf-sur-Loire, in the Loire Valley

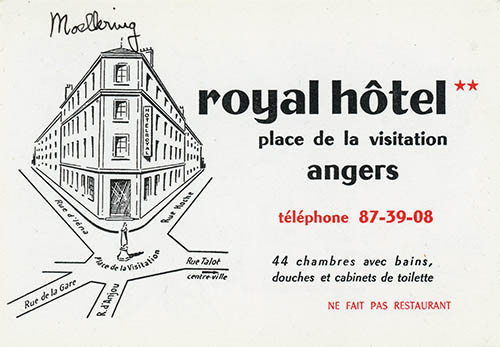

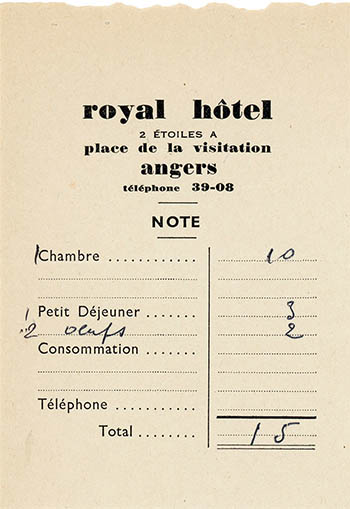

William spent the next six days in the “Garden of France,” following the course of the Loire and its tributaries towards the sea. He visited the Château de Blois (where Joan of Arc was blessed before the Seige of Orléans) and the monumental château overlooking the Vienne in Chinon (where Joan of Arc declared Charles VII the rightful heir to the French throne). By the 20th he had arrived in Angers, the medieval seat of the Plantagenet dynasty, and spent the night at Royal Hotel.

showers and toilets. Does not have a restaurant...

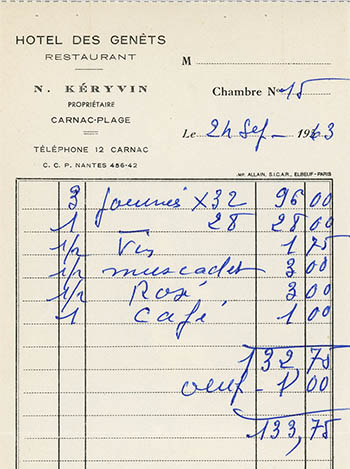

William followed the Loire as far west as Nantes, where he stopped for dinner. He then turned north-west and travelled another 150 kilometers along the pink granite coastline to the seaside resort of Carnac-Plage in Brittany, where he stayed at the historic Hotel des Genêts. According to his receipt—in fact, according to nearly all of his receipts—he had wine with dinner and eggs with breakfast.

was operated from 1926–1993 by three generations of the Kéryvin family.

It was razed in September 1998 after a fire destroyed the building.

“A witness to Carnacois history disappears,” wrote Le Télégramme

After a few days on the beach in Carnac, William travelled north, filled his tank in St. Méen (30.6 L @ 0.98 Fr/L), and by the 24th had arrived in Dinan, the half-timbered walled city on the banks of the Rance. The next day he stopped in Cancale, the oyster capital of France, and spent the night at the Hotel Continental. Although there is no specific record of it, it seems unimaginable that he didn’t visit the nearby island monastery of Mont Saint-Michel.

He then headed further north, through the bocage of the Cotentin Peninsula, and by the 27th had arrived at Coutances in Normandy. William then visited the Greco-Roman ruins at Valognes and stayed at the Hotel l’Agriculture (and payed an extra 0.50 Fr to use the phone). By the 30th he had made it to Rouen (where Joan of Arc was burned at the stake by the English). On his way back to Germany he got gas and stayed the night in Compiègne. He arrived back in Darmstadt, via Metz and Saarbrucken, on the evening of October 3rd.

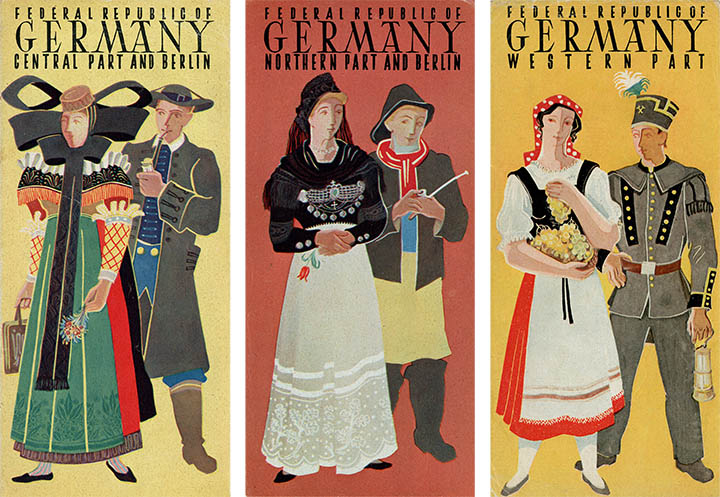

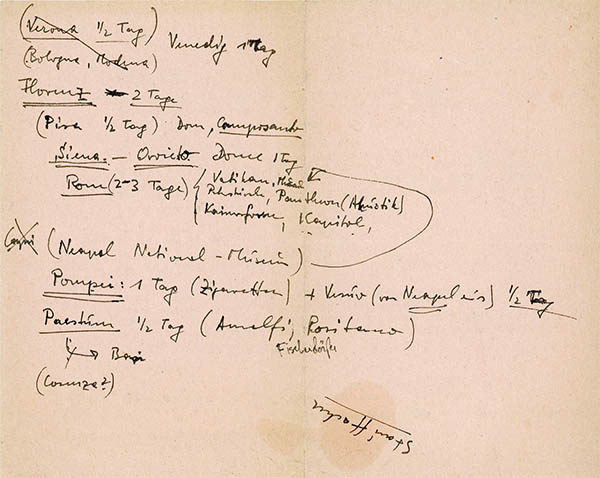

Although William’s epic road trip through northern France was the best documented vacation in the box, it was by no means the only one. The box was filled with town plans and road maps, guidebooks, tourist brochures and pamphlets, as well as handwritten notes and loose-leaf itineraries—the ephemera from dozens of trips, both real and imagined. I thought there had to be an interesting story in that box—that if I spent enough time researching its contents, I could learn something about William’s life. Call it historical curiosity or, perhaps more accurately, forensic voyeurism.

As it turns out there is an interesting story in the box—it just wasn’t anything like the one I had imagined.

I—Cincinnati, Pasadena, Urbana–Champaign.

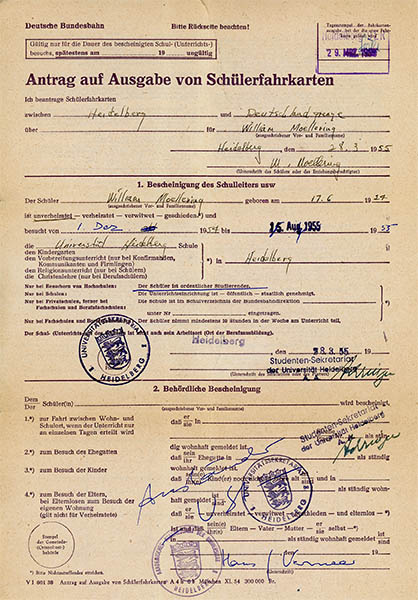

Let’s begin with an unlikely document—a fragile 1955 Deutsche Bundesbahn application for student-rate train fares. It was the only thing in the box that not only stated William Mollering’s full name but, in its Teutonic rigor, included his date of birth as well. Using the information from this ur-document I began to trace his early life and academic career.

Marjorie Alice Mahurin (born January 12th, 1896) married the wholesale grocer Arthur H. Moellering (born April 12th, 1896) on June 6th, 1921, in Fort Wayne, Indiana. Their only child, William Marshall Moellering, was born on June 17th, 1924. The couple eventually divorced and Marjorie moved to Cincinnati. In July of 1931 she married the plywood salesman Loring Mackie Myers, who came to Cincinnati from New Orleans. William’s half-brother, Loring Myers, Jr., was born the next year.

According to his vita, William graduated in 1942 from Terrace Park High School, in a suburb of Cincinnati. That fall he enrolled at the California Institute of Technology, but, like most young men of his generation, his education was interrupted for service in WWII.

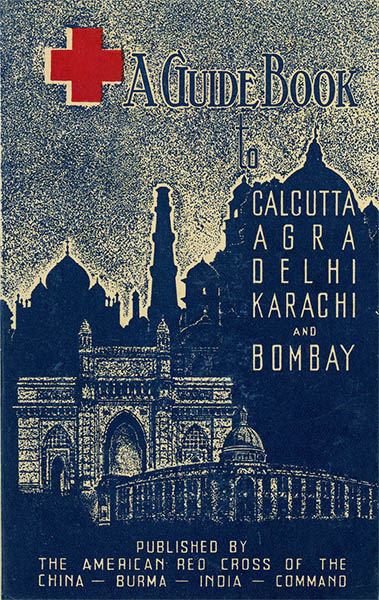

Based on a few blurbs provided by his mother to the Cincinnati Enquirer, William, while at Caltech, served as a Private first class in the Army Reserve and trained at nearby Fort MacArthur. In late 1943 he was accepted into the short-lived Army Specialized Training Program, where he studied engineering. In the box there was a Red Cross Guidebook with few menu cards dated December, 1945, suggesting that after the ASTP was dissolved, William was stationed in Calcutta, where the US Army Eastern Air Command was headquartered.

After his discharge from the Army, William returned to Caltech and finished his undergraduate degree in electrical engineering in 1949. In September, 1950, just before he started graduate studies at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, William and his family went on a road trip out west.

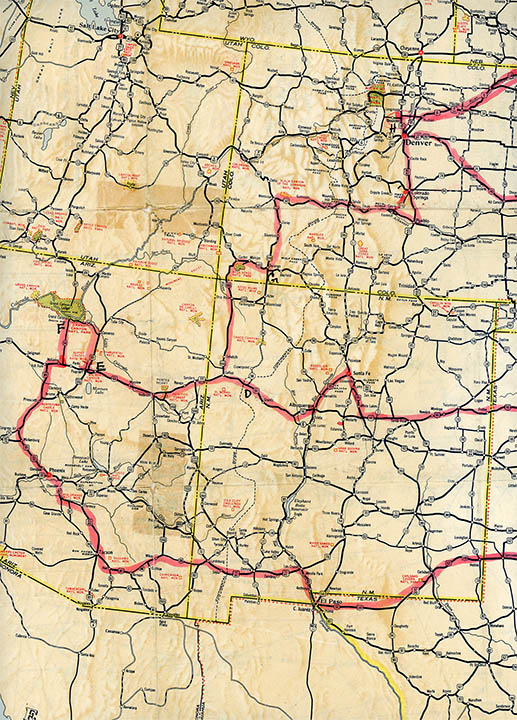

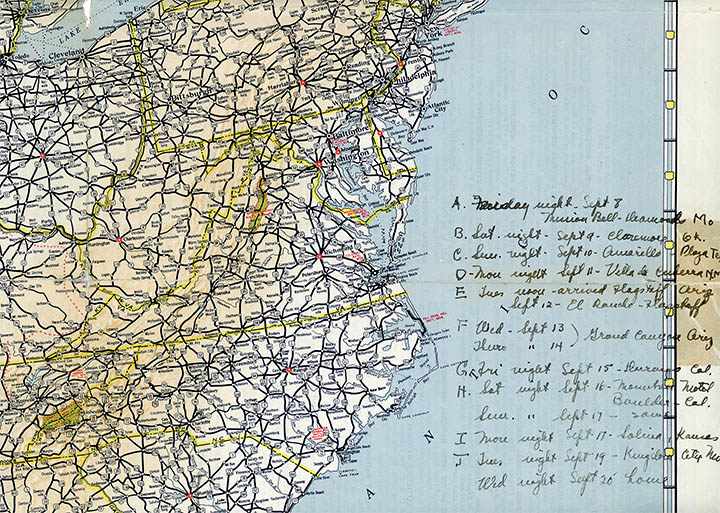

Following William’s annotated pre-interstate AAA road map, the family, beginning in Cincinnati, travelled to St. Louis, then followed historic Route 66 through Oklahoma, the Texas panhandle, New Mexico and Arizona. By day five they had made it as far west as the Grand Canyon. On their return they headed north: through Durango and Boulder, then Kansas, Missouri, Illinois and Indiana. 10 states in 12 days—a vacation that could fill a carousel with Kodachrome slides.

William completed his masters in physics in 1951. He was then accepted into the school’s doctoral program and was advised by Francis E. Low, who had worked on the Manhattan Project during the War. William received his Ph.D. in 1954 with a dissertation titled The Effect of the Structure of the Proton on the Hyperfine Interaction in Hydrogen.

II—Heidelberg.

William was awarded a Fulbright Scholarship (one of 409 granted that year) and on the first day of December, 1954, he began post-doc studies at the venerable University of Heidelberg under J. Hans D. Jensen, who was developing the theory of atomic shell structure, which earned him a share of the 1963 Nobel Prize in Physics.

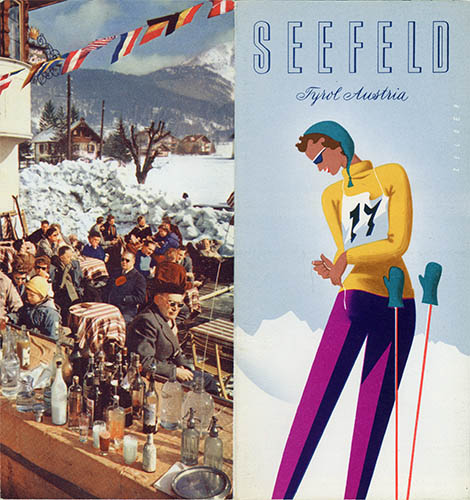

The earliest of the dozen or so Tyrolean ski brochures in the box had rate inserts for the 1954/55 winter season, so it appears that William’s new university colleagues introduced him to the sport. His Deutsche Bundesbahn application—dated March 29th, 1955—could very well have been for discounted train tickets for his first ski trip.

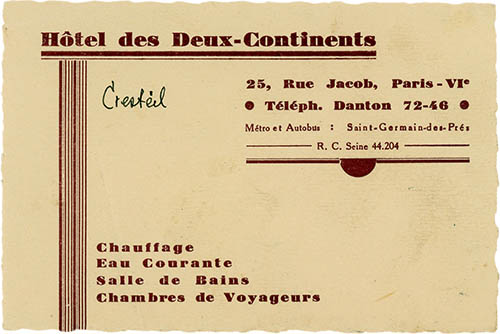

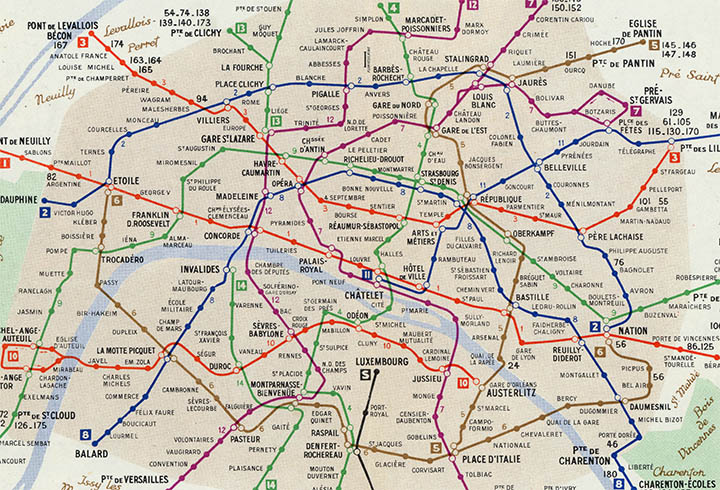

In addition to his ski trips, William also managed to visit Paris at least once (and possibly twice) while in Heidelberg.

Telephone: Danton 72-46. Heat. Running water. Bathrooms. Guest rooms

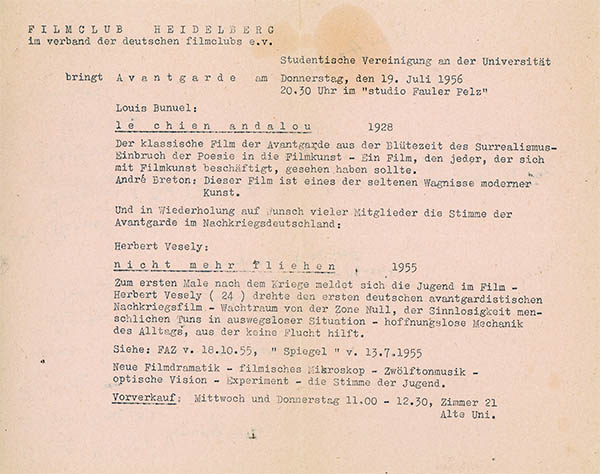

Fulbright Scholarships typically last 12 months, but it appears that William spent at least two years in Heidelberg; among his papers was this circular for the Student Film Club from July, 1956:

heyday of the Surrealist invasion of poetry into cinematic art. A film that anyone who

deals with cinematic art should have seen. André Breton: This film is one of the

rare ventures of modern art.

Whether he actually took this trip is unknown.

III—Princeton.

In the box was a manila envelope from the Quebec Tourist Bureau with a canceled 5-cent James Monroe stamp. Based on the address and the date of its contents, William had returned to America and by 1958 was now at the Palmer Physical Lab at Princeton University (where, supposedly, Einstein had once lectured). It seems likely that he was there to work with Eugene Paul Wigner, who was an expert in quantum symmetry and not only knew J. Hans D. Jensen, but shared the 1963 Nobel Prize with him as well.

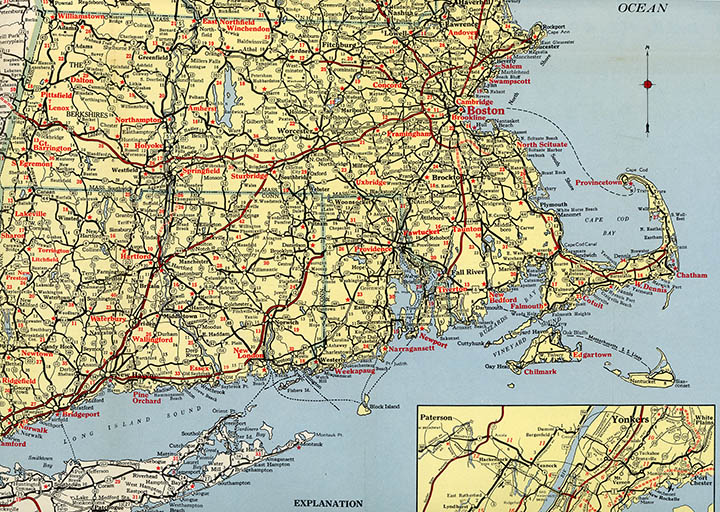

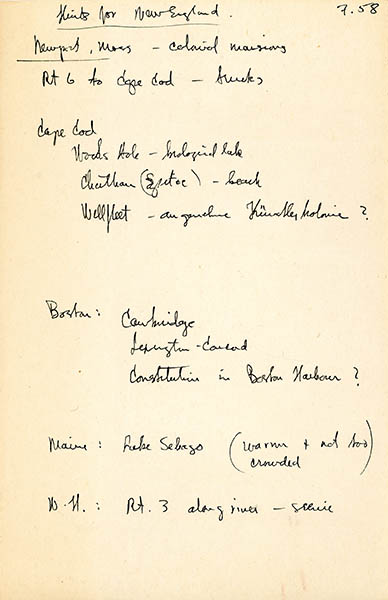

The brochure from Quebec was a ski brochure which advertised the “marvelous snow conditions found year after year” in the Laurentian Mountains. It seemed that William was now hooked on the sport. The rest of the envelope’s contents, however, were pamphlets, guides and an itinerary for William’s July, 1958, New England road trip:

“Travel New England the ‘Hotel Way!’ ”

IV—Darmstadt.

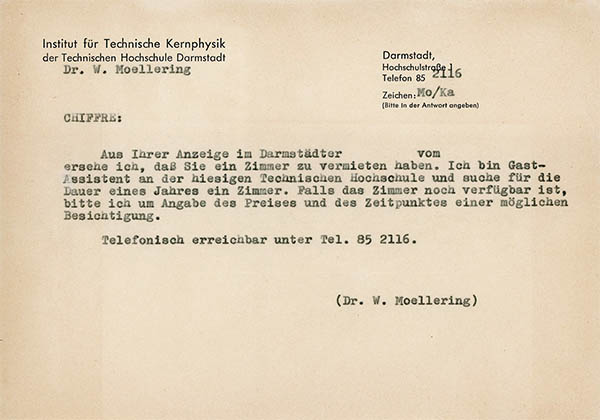

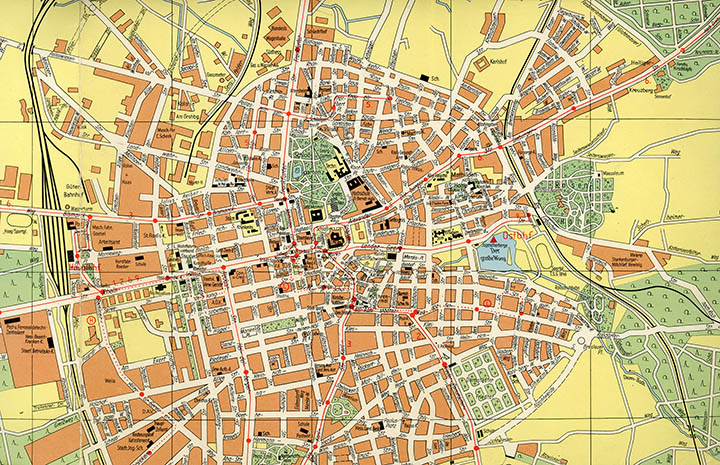

Tucked into a map folder in the box was a form letter from William on official stationary asking to view an apartment. Along with the letter were dozens of brokered room receipts, each with a different address and landlord. From the letter and the dates on the receipts, it appears that in September, 1961, William had gone back to Germany to be an assistant at the Institute of Nuclear Physics at the University of Darmstadt.

at the local Technical University and I am looking for a room for one year. If the room is still available, please tell me the price and the time of a possible visit.

Reachable by phone at Tel. 85 2116.

While in Darmstadt, William bought a used car as well as a 23-line notebook. Reading through his ersatz log book, it became evident that with a car—and six weeks of vacation each year—he began to travel much more frequently. Some of his entries were for short trips in Germany—Eisenstein, Dachau and Bonn—but others were for two-week or month-long vacations during school breaks.

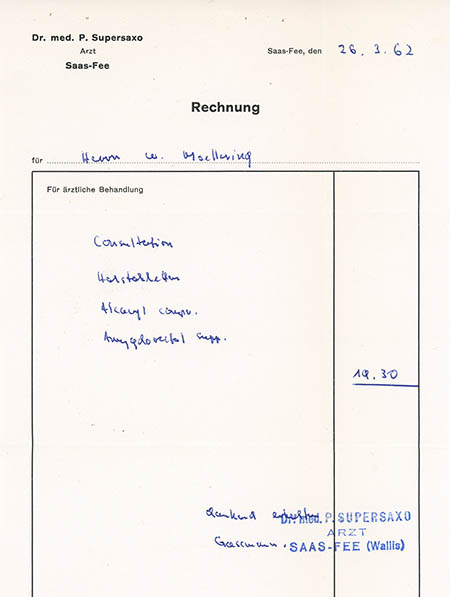

During the winter break in March, 1962, William left for Switzerland. He drove past Basel and Bern, through the Rhône Valley, then up into the Pennine Alps to Sass-Fee. During his two-week ski trip he apparently fell ill and had to visit the local doctor. Fortunately, based on the medications he was given, it was likely minor—only a sore throat. He returned home, by way of Visp and Basel, on the 4th of April.

Berann, considered the father of the cartographic panorama, began his career illustrating

Austrian and Swiss ski resorts. He would be best known, however, for illustrating

Marie Tharp and Bruce Hezeen’s groundbreaking 1977 map of the ocean floor.

Bill

For medical treatment

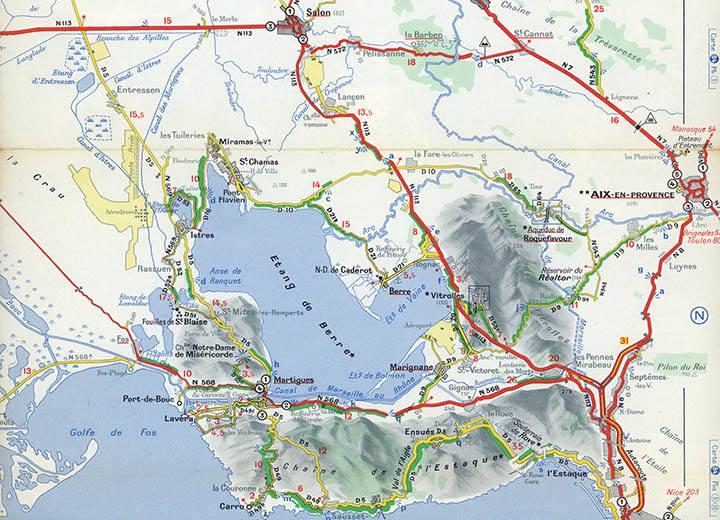

In September, 1962, between summer and winter semester, William took his first road trip through France. Based on his log book entries, he left Darmstadt on the 5th and spent the next night in Kehl. He then visited Lons-le-Saunier and the ancient Roman outpost of Nîmes. By the 19th he made it as far south as Aix-en-Provence.

After ten days driving through the out-of-season lavender fields of Provence and visiting the sandy beaches of the Riviera, he turned north and visited Logis-du-Pin, La Mure and Lyon (France’s second city) in the French Alps. On his route back to Darmstadt he stayed over in Basel in Switzerland. 25 days, 2990 kilometers and 156 Francs in gas (plus the cost of that new battery).

The next spring he returned to the Pennines and spent two weeks skiing in Verbier, where he stayed at the Hotel Mont-Fort, and noted that the average cost for lunch and dinner was 9⅓ francs.

That September he took his epic road trip through northern France.

I can’t help but imagine that William had a good time in Switzerland or France (or, for that matter, anywhere else he went), but there’s nothing in the box to confirm that. There are no photographs of him in front of historic monuments, or postcards to be sent home, or even notes about the restaurants, hotels or ski resorts he visited. Perhaps his photos and souvenirs are in some other album or box I’ll never see, or perhaps the box itself was his souvenir. Or perhaps he enjoyed the planning more than the actual vacation itself.

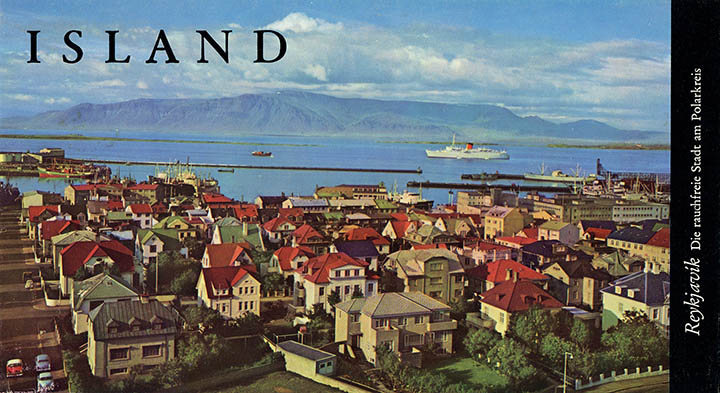

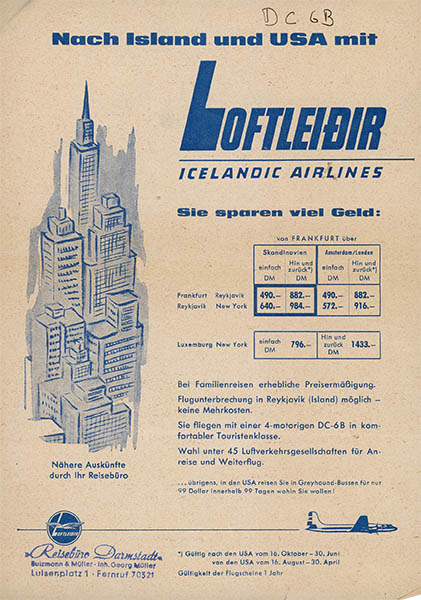

Among the last things in the box are a half-dozen brochures and folded, paper-clipped flyers from a travel agent for a plane trip to Iceland—a destination that, even for someone living in Europe at the time, would have been somewhat exotic.

travelling to Europe in the late 1960s that it earned the nickname “the hippie airline.”

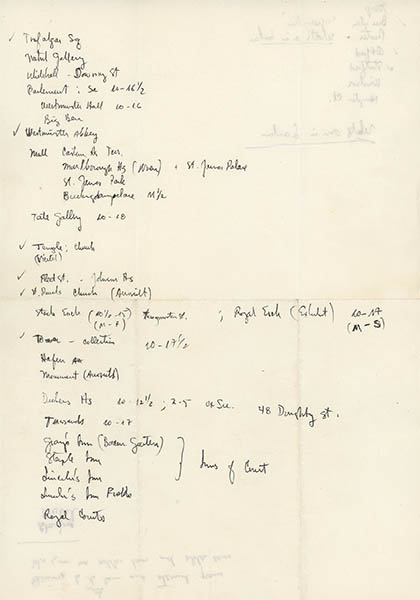

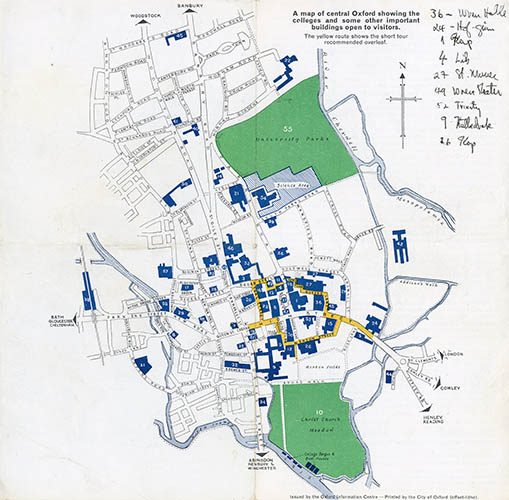

Whether William ever made it to Reykjavik is unknown, but he did take a trip to London and Oxford in 1964.

VI—Cincinnati.

The box represented nearly 20 years of William’s life, from an Army private stationed in Calcutta in the 1940s to a particle physicist teaching in Darmstadt in the 1960s. However, after the box ends in 1964—when William was 40 years old—there is surprisingly little information about his later life.

In a letter to the editor published in the Cincinnati Enquirer in November, 1967, he gave his address as his mother's house outside of Cincinnati. William’s step-father had died a year earlier and his brother was now an attorney with a new family in Los Angeles. Perhaps he returned home to take care of his 70 year-old mother.

Whatever the circumstances of his return, it appears that once back, William stayed in Cincinnati for the rest of his life. In a few letters to Physics Today, where he complained about the Equal Rights Amendment (1979) or the the cost of the proposed Superconducting Super Collider (1988), he listed Cincinnati (without an institutional affiliation) as his address.

William had studied under two Nobel laureates and trained at some of the best universities in the world. He was clearly preparing for a career in academic research, but his last scientific paper was published in 1956 and after his stay in Darmstadt there is nothing I can find to suggest what he did next. Did he teach? Did he go into private industry? Did he continue to travel? Did he do something else altogether? I simply have no idea.

William died at the Christ Hospital in Cincinnati on February 27th, 2002, at the age of 77. He was cremated and there was no published obituary or death notice. He never married and left no immediate family. His closest relative, his brother Loring, Jr., died in Arizona in 2017. The box appears to be all that’s now left of his life.

—March 14th, 2018. Cartography