41

The Radio Nurse

Noguchi as Industrial Designer

This oddly unsettling but somehow familiar and reassuring radio receiver, the Zenith Radio Nurse, is, if nothing else, a masterful example of Machine-age design. The bakelite1 shell was, according to the molding on the back of the case, “Designed by Noguchi” – as in the Japanese-American sculptor Isamu Noguchi.

In response to the Lindbergh kidnapping (1 Mar 1932) and the sensational “Trial of the Century,” Commander E.F. McDonald, Jr, the president of Zenith Radio, designed an ad-hoc intercom system to listen in on his infant daughter on the yacht where they lived. He decided to develop his intercom into a commercial product: “a device which will be simple, beautiful and at the same time distinctively different from any inter-communicating set or radio now in use” and commissioned Isamu Noguchi to design the receiver. The Zenith Radio Nurse, introduced in 1937, was the first baby monitor.

The Radio Nurse and the Guardian Ear

The Radio Nurse (the Guardian that Never Sleeps) consisted of the Radio Nurse receiver and a rather nondescript enameled-metal Guardian Ear transmitter. The novel system never sold well – it was relatively expensive and plagued by technical problems.2 In the wake of anti-Japanese sentiment following Pearl Harbor, many of the receivers were destroyed, making the radio somewhat scarce today.

Isamu Noguchi (野口 勇) (17 Nov 1904–30 Dec 1988) was the illegitimate son of the Japanese poet Yone Noguchi and his American editor Léonie Gilmour. After spending his childhood in Japan and his adolescence in Northern Indiana, he left to study art in New York under Gutzon Borglum. A Guggenheim fellowship took him to Paris where he studied under Brancusi, and later, back in NYC, he was befriended by, and worked with, R. Buckminister Fuller.3

Noguchi would spent the rest of his life synthesizing Japanese tradition with Western Modernism. He created an impressive body of sculptural pieces, but also designed theater sets and large-scale public spaces, such as parks, gardens and playgrounds. To the casual modernist, however, he is perhaps best known for his industrial design, including tables for Knoll, Alcoa and Herman Miller,4 as well as his extensive series of Akari Lamps. But before all of this was the Radio Nurse.

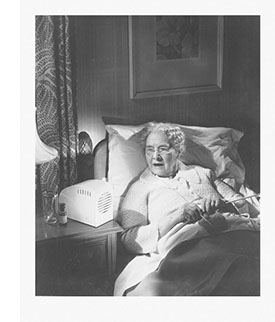

Promotional photos, Third Annual Modern Plastics Competition, 1938

Noguchi’s design manages to be both abstract and figurative at the same time. It looks like a faceless bust with the suggestion of a nurse’s cap in back, but also like an Art-Deco radio. It represented his exploration of the the notion of the interchangeability of biological and machine forms, and well as his concept of everyday objects as sculpture. Also, the speaker grille is reminiscent of the Japanese Kendo mask, and is typical of Noguchi’s combination of Eastern and Western forms.

In Nov 1938 the Radio Nurse won first place in the household goods category of Modern Plastics Magazine’s Third Annual Modern Plastics Competition. The next year it was displayed at the Whitney Museum’s annual sculpture exhibition, where Time magazine called it the “most exotic” exhibit in the show but also said it was “prettier as a radio than as a nurse.” Today it is widely considered a modern design masterpiece.

1. The case was manufactured for Zenith by the Chicago Molded Products Corporation and Kurz-Kasch, Inc., Chicago, Illinois.

2. The Radio Nurse, originally priced at 29.95 USD, consisted of the TA Guardian Ear transmitter and the RA Radio Nurse receiver. The TA microphone output was amplified and used to modulate a 300 kHz oscillator (adjustable between 250-450 kHz) and the signal was coupled to the 60 Hz AC power line. The RA receiver picked up that signal from the line, demodulated and amplified it, and fed it to a speaker. In use, however, the Radio Nurse suffered from distortion, RF interference and rogue broadcast pickup. Here is the technical manual, including schematics.

3. For more information about Noguchi and his work, see the Noguchi Museum (NY) or the Noguchi Garden Museum (Japan) websites.

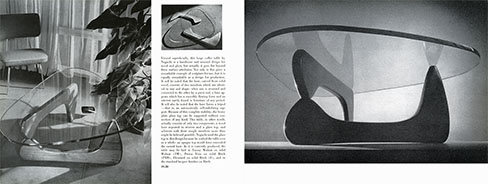

4. Noguchi’s IN-50 for Herman Miller is a spectacularly minimalist sculptural design and may very well be the iconic mid-century coffee table. It was introduced in 1947, reintroduced in 1984, and is still available today. From the 1950 Herman Miller catalog:

28 Sep 2009 ‧ Design