This 30 × 40" oil painting by Andrew Loomis, titled Maytime, was the illustration for the 1944 Brown and Bigelow Dionne Quintuplets promotional calendar. If you were around at the time it was likely that your bakery, dairy, florist or laundry – or perhaps your insurance company, funeral home or farm bureau gave you one of these at Christmas in 1943.

When Oliva and Elzire Dionne of Corbeil, Ontario were expecting their sixth child they were fairly certain that Elzire was carrying twins.1 They would turn out to be about 40% right: on 28 May 1934, with the help of the local doctor Allan Roy Dafoe and two midwives, Elzire gave birth to five girls: Yvonne, Annette, Cécile, Émilie and Marie. They were the world’s first surviving quintuplets.2

In an unprecedented move the parents were found to be “unfit” (i.e., they were too poor) and the quints were made special wards of the province under the Dionne Quints Guardianship Act of 1935. The girls were removed from their home and placed in the newly-built Dafoe Hospital and Nursery (AKA Quintland), directly across the street from their parents farmhouse.

In nearly sterile isolation under the custody of Dr Dafoe, the girls were observed, measured, analyzed and recorded in minute detail.2 While the good doctor was busy using the quints as medical test subjects the the provincial government was busy turning them into a tourist attraction. At the height of the Depression as many as 6000 visitors a day came to see “Canada’s greatest natural wonder.” Souvenir stands soon lined the street selling everything from postcards and tinted pictures to fertility stones from the family farm. The girls had been turned into a freak show and anyone even remotely connected to them began to cash in on their popularity. “Money was the monster,” they wrote, “So many around us were unable to resist the temptation.”

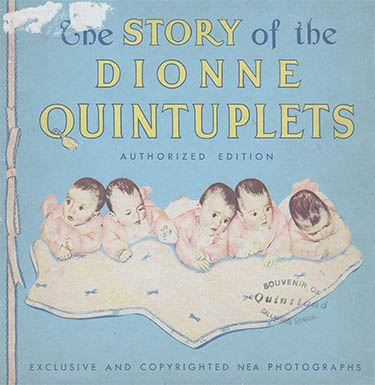

Souvenir book from Quintland, 19353

1937 photo

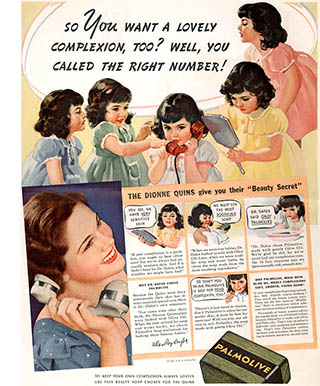

The quints were a symbol of hope during the Great Depression and, perhaps not surprisingly, became a marketing juggernaut. Their photos appeared in thousands of magazine articles. Their likeness was licensed for everything from books and postcards to collectable spoons and Madame Alexander dolls. They endorsed Karo (the energy syrup), Baby Ruth, Palmolive and even Fisher Auto Body.

Palmolive ads, 1937, Andrew Loomis. Duke

They starred in several 20th-Century Fox films:

Theater card, Five of a Kind, 1938

Of all their merchandise, however, it was their calendar that became the most ubiquitous. In 1936 the St. Paul, MN-based Brown and Bigelow, then the largest calendar company in the world, licensed their image and commissioned the young artist Gil Elvgren to supply the yearly illustrations:

The Dionne Quintuplets, 1937 calendar, Gil Elvgren

Five Little Sweethearts of the World, 1938 calendar, Gil Elvgren

Five Little Sweethearts, 1939 calendar, Gil Elvgren

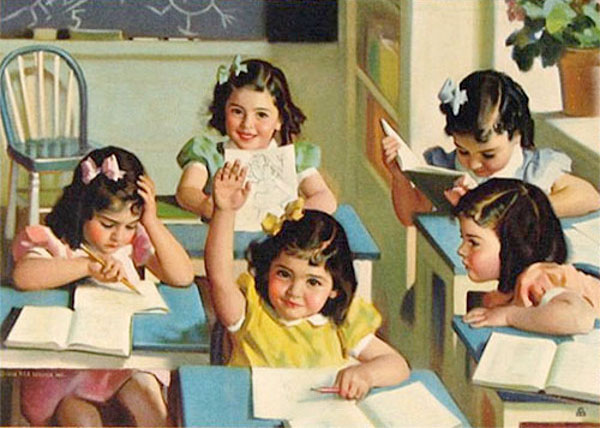

Elvgren was lured away by cross-town rival Louis F. Dow to illustrate pin-up calendars so Brown and Bigelow hired the illustrator and art instructor Andrew Loomis to continue the quints calendar. Loomis, using just photos and his own daughter as a model illustrated their calendar until 1955, although as he later admitted he had some difficulty painting the sisters during their awkward adolescent years.

School Days, 1940 calendar, Andrew Loomis

All Dressed Up, 1941 calendar, Andrew Loomis

Spring Time, 1942 calendar, Andrew Loomis

Sunny Days, 1943 calendar, Andrew Loomis

After a protracted legal battle the Dionnes’ finally regained custody of their daughters and in 1943 the family moved into a new Georgian mansion (paid for, of course, out of the quints trust). Although the circus of Quintland came to an end, the girls didn’t fare any better with their parents. Oliva deeply resented the hardships they had brought on the family. As the sisters said “Who could ever count the times we heard, ‘We were better off before you were born, and we'd be better off without you now?’ ” According to their later allegations, he even sexually abused them as teenagers. As soon as the sisters turned 18 they left home and cut off virtually all contact with their family.

Harvest Days, 1945 calendar, Andrew Loomis

Queens of the Kitchen, 1946 calendar, Andrew Loomis

Everybody Helps, 1947 calendar, Andrew Loomis

First Dates, 1948 calendar, Andrew Loomis

The Brown and Bigelow catalog offered 60–70 designs each year but the majority of sales were from a few established artists and genres including Maxfield Parish landscapes, Norman Rockwell Boy Scouts, Lawson Woods wildlifes, Winold Reiss Indians and, of course, Cassius Marcellius Coolidge poker-playing dogs. Despite these staples, however, the quints calendar was a perennial bestseller – it was even their top seller in 1940. In all Brown and Bigelow printed millions of quints calendars and paid their trust several hundred thousand dollars in royalties.

Fifteen All, 1949 calendar, Andrew Loomis

Sweet Sixteen, 1950 calendar, Andrew Loomis

Out for Fun, 1951 calendar, Andrew Loomis

Smooth Sailing, 1952 calendar, Andrew Loomis

The Dionne Quintette, 1953 calendar, Andrew Loomis

Émilie died of epilepsy at age 20 on 6 Aug 1954 but Brown and Bigelow, already well into next years production cycle, saw fit to publish one more calendar of the quints as 21-year old adults:

Grown Up, 1955 calendar, Andrew Loomis

After Émilie’s death interest in the quints began to wane but they would never lead normal lives. Completely ill-prepared for the real world, the surviving sisters went through difficult marriages and divorces, failed businesses and financial hardships and suffered chronic health problems.

It has been estimated that the quints generated some 500 million CDN in revenue over the years, but of course the girls never received any of it. By the 1990s the three remaining sisters were living on a combined 700 CDN/month pension and petitioned the government for an accounting of their trust. Under public pressure Premier Mike Harris finally awarded them 4 million CDN for “reparations.” A classic case of too little, too late.

1. Oliva (1903–1979) and Elzire (Legros) (1909–1986) Dionne were married on 15 Sep 1926 and had a total of 14 children. Here is a 1940 family portrait:

2. For a biography see: Berton. Pierre. The Dionne Years: A Thirties Melodrama. New York: Norton, 1978 (WorldCat), or Brough, James. We Were Five: the Dionne Quintuplets’ Story from Birth through Girlhood to Womanhood. New York: Simon and Schuster, 1965 (WorldCat).

3. For a typical example see: Dafoe AR, Dafoe WA. The Physical Welfare Of The Dionne Quintuplets. Can Med Assoc J. 1937 Nov; 37(5): 415–423 (online).

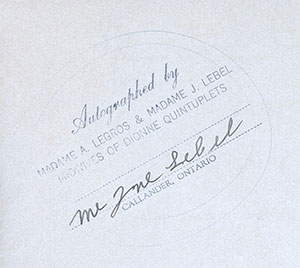

4. The Story of the Dionne Quintuplets. Racine, Wisconsin: Whitman Publishing, 1935 (WorldCat). This autographed souvenir book was purchased from the roadside stand operated by Madame Legros and Jane Lebel – the midwives who delivered the quints:

11 Feb 2012, updated 24 Aug 2015 ‧ Illustration