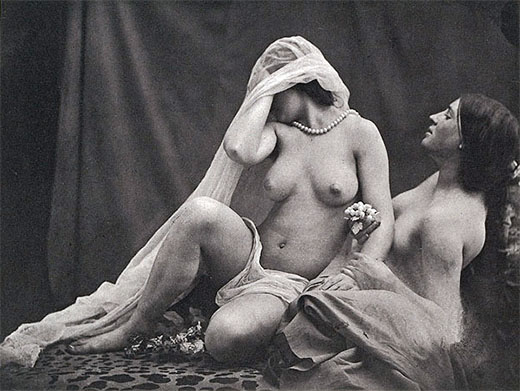

This allegorical tableau vivant, or mise-en-scène was created by Oscar Rejlander in 1857. It depicts a philosopher, or a sage, or perhaps a father leading two young men towards manhood. One (to the left) looks towards vice; gambling, wine and prostitution, and the other, with perhaps less enthusiasm, looks towards virtue; religion, industry and family. Penitence, in the center, looks toward the right, rejecting vice. The image was the first publicly exhibited photograph of a nude in England, the first major art photograph and the first photo-montage.

Study, Penitence, photogravure, 1857. Art of the Photogravure

Oscar Gustav Rejlander (1813–18 Jan 1875) was born and educated in Sweden. After studying painting in Italy and Spain he settled in England in 1846. Initially his interest in photography was merely as a means of recording works of art and, around 1850, he had what could best be described as a crash course in the calotype process from Nicholas Henneman in London and soon switched from portrait painting to photography. His earliest experiments with combination printing, around 1855, were based on purely technical issues, i.e.; it was too hard to get all of the elements of a composition in focus, so he individually photographed each part of the image and combined them all in the final print. After solving this problem he was able to create even more complex compositions and began to see the photograph as a means of art in and of itself.

Rejlander intended Two Ways of Life to depict the underside of London as described in George Reynold’s popular serialized novel Mysteries of London 1 and staged the tableau after Raphael’s famous School of Athens:

School of Athens, Raphael, 1511

The complexities of the composition required him to photograph the subjects (anonymous actors from traveling troupes, according to Rejlander, but more likely London prostitutes) individually or in small groups. The wet-plate negatives – 32 in all – were then meticulously exposed onto a carefully matted albumen silver print, starting with the foreground images. The final 31" × 16" print required two sheets of photographic paper and took all of six weeks to complete.

The image, not surprisingly, caused a sensation. One reviewer described it as “magnificent....decidedly the finest photograph of its class ever pronounced” and the print was shown in March 1857 at the Manchester Art Treasures Exhibition (one of the first to exhibit photographs along with other art), where a copy was purchased (for 10 guineas) by Queen Victoria for the Prince Consort.2 Even with royal patronage, however, many felt that the photographic nude crossed the line of decency. The Scottish Society even refused to display it at their Exhibition in Edinburgh.3

In defending the Scottish Society, Thomas Sutton, editor of Photographic News, stated: “There is no impropriety in exhibiting works of art such as Etty’s Bathers usurped by a swan,4 but there is impropriety in publicly exhibiting photographs of nude prostitutes in flesh and blood truthfulness and minuteness of detail.” Rejlander attempted to defend his models stating that “There are many female models whose good name is as dear to them as any other women.” To which Sutton replied “We have no morbid sympathy for Traviates and Fleurs de Marie, and do not desire to see such unfortunates figuring in a state of nature in composition photographs upon the walls of a public Exhibition room.”

Perhaps in response Rejlander produced a second version with the wise sage looking toward virtue:

The technique of composite printing also proved controversial. Many felt that an elaborately staged art composition was inappropriate for the “mechanical” medium of photography. It was picture making instead of picture taking, a theory that Rejlander would eventually concede to with in his 12 Feb 1863 address to the South London Photographic Society, “An Apology for Art-Photography.” 5

Rejlander continued to photograph, although he largely gave up on the composite art image, stating in 1859 “I am tired of photography-for-the-public, particularly composite photos, for there can be no gain and there is no honour.” His later works included anecdotal and genre images, such as his social commentary Poor Joe, as well as artists’ studies and the photographs for Darwin’s The Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals. He became ill in 1874 and died, penniless, the next year.

From the Poor Joe series, ca.1860

1. Reynold, George. The Mysteries of London. London: John Dicks, 1845 (WorldCat, online, audio). The book was one of many “Penny Dreadfuls” – lurid serialized novels with each installment costing one penny.

2. Rejlander made at least five prints, one was sold to Queen Victoria, one to Sir David Brewster, another to an unidentified gentleman in Streatham and the last was presented to the Royal Photographic Society in 1925 and is the only known original print still in existence..

3. The Scottish Society did eventually display it in 1858, but curtained off the entire left half of the image. In 1866 they made up for this with a dinner in his honor and an exhibition of his works.

4. More commonly known as Bathers Surprised by a Swan, William Etty, 1841. The subject matter is exactly as the title implies: two nude female bathers are suprised by the appearance of a swan:

5. Rejlander, Oscar. “An Apology for Art Photography.” Address to the South London Photographic Society, 12 Feb 1863 (online).

19 Dec 2008, updated 14 Dec 2014 ‧ Photography