The XB-70

My Dad and the Cold War

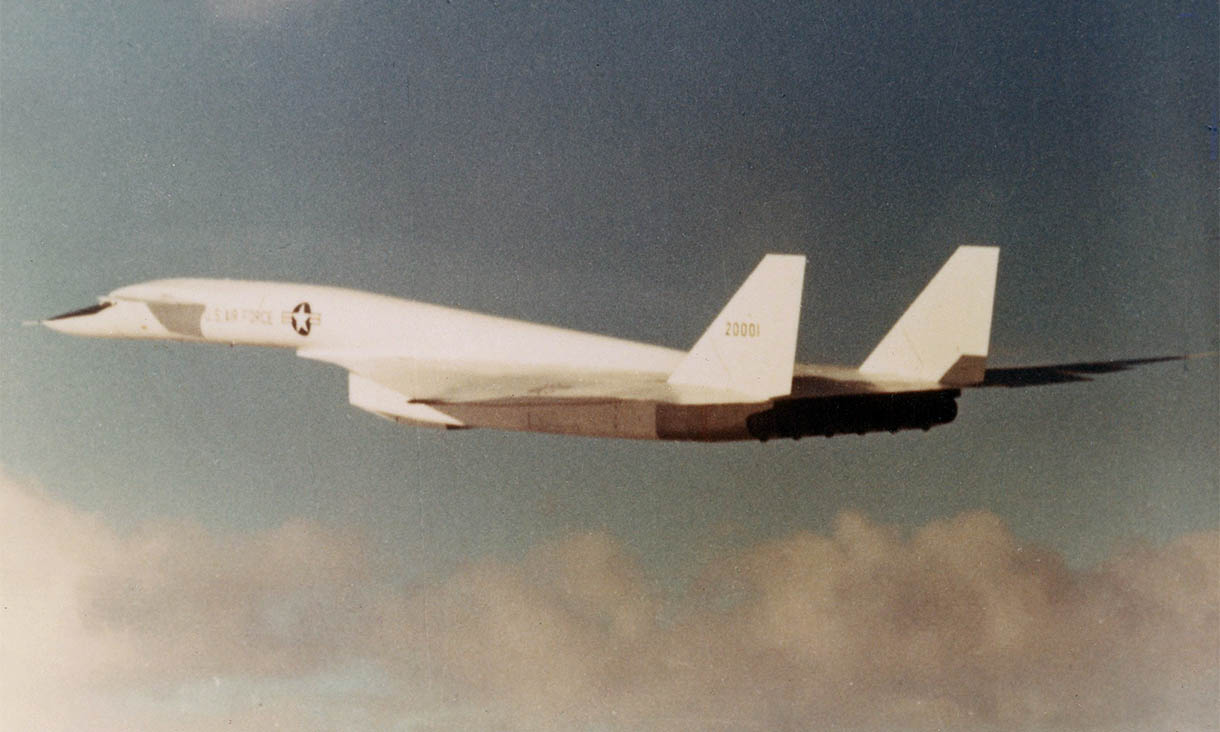

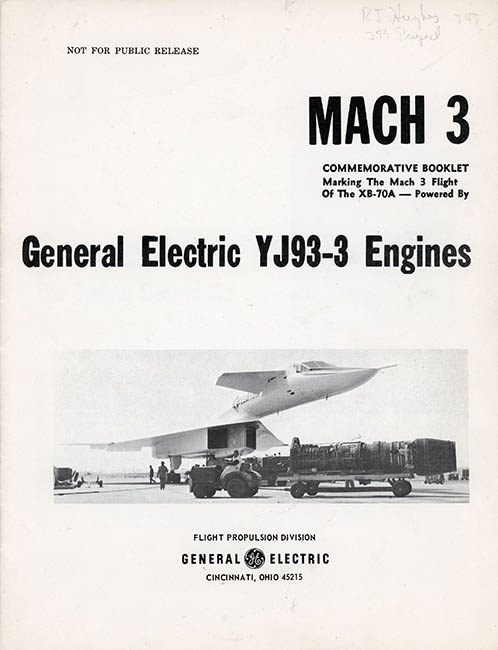

On the occasion of the public unveiling of the XB-70 Valkyrie, brigadier general Fred Ascani stood at his podium and began addressing the crowd at North American Aviation’s plant no. 42 in Palmdale, California. General Ascani was the Air Force’s program director for the project and knew as much as anyone about the plane, but as the massive delta-winged XB-70 was towed out of the hangar he stopped his prepared speech, turned to look, and, like everyone else in attendance that afternoon, simply stared in disbelief.

The XB-70, conceived during the height of the Cold War as a replacement for the B-52, was perhaps the most audacious plane ever commissioned by the Air Force. It was designed to fly higher and faster than any enemy fighter, drop thermo-nuclear bombs over targets in the Soviet Union, outfly the blast radius, and then return home without ever refueling. It was intended to be the ultimate display of American technological prowess; the ultimate weapon of mass destruction. The plane wasn’t simply an evolution of any current design, but a leap in technology so advanced that it seemed to come from a science-fiction movie. “She is so unlike other aircraft that comparisons are almost meaningless,” wrote Mel Hunter.

But by the time that first XB-70 rolled out onto the tarmac in the California desert it had already been replaced by a new weapon of mass destruction—the ballistic missile. The plane became a political pawn and was eventually reduced to a just a test program.

By this time my dad had spent six years working on the XB-70 project. So this is the story of my dad’s brush with the Cold War and, as best as I can piece together, the story of my dad before he was my dad.

I.

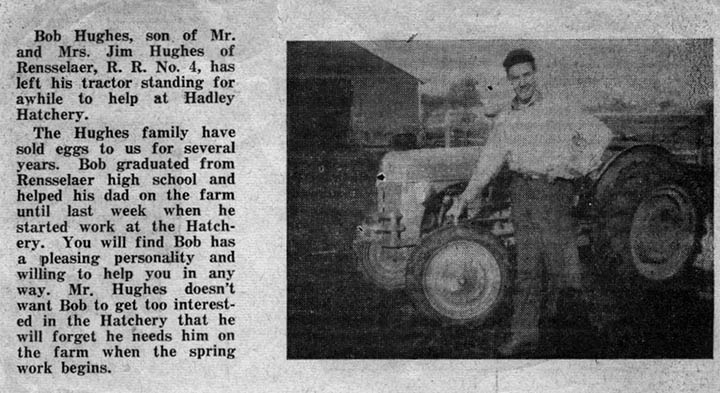

My dad was the oldest son of a family of tenant farmers in Nothern Indiana. He grew up during the Depression and was so poor, at least according to the family story, that after the farm was electrified by Roosevelt in the mid-1930s, my grandfather had to choose between buying him a baseball glove or buying lightbulbs for the farmhouse. Obviously, my dad couldn’t make a living on a farm that could barely support my grandfather, so after high school he went to work; first in a hatchery (a job he hated), then for a company that built miniature trains for amusement parks (a job he liked).

In November, 1952—when my dad was 22—it became clear that he was going to be drafted into the Army and sent to fight in Korea. Instead he enlisted in the Navy, trained as an aviation structural mechanic, and, among other things, spent time aboard the escort carrier USS Sitkoh Bay. “It was the best thing that ever happened to him,” my mom said, “If it weren’t for the Navy he would have ended up back on a farm in Indiana.”

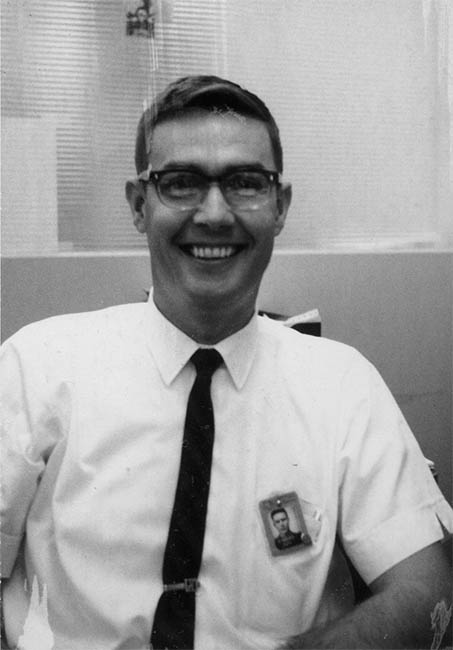

After he was discharged in 1956, my dad didn’t return to the farm, but, with the help of a friend, got a job with the Flight Propulsion Division of General Electric in Evendale (just outside of Cincinnati), initially working night shift in the Controls and Accessories department. This is when he met my mom, who was a secretary in a different department. “He would bring me lunch after working all night,” she told me. They were married within a year.

II.

While my dad was fixing airplane hydraulic systems at the tail end of the war, Eisenhower, the newly-elected president, was working on something a little bigger: a national security policy to counter the growing Soviet military threat in Europe. This “New Look” policy, as it was called, relied on a nuclear deterrent with the Strategic Air Command as its’ centerpiece. The idea was that America didn’t need to match the Soviets’ perceived superiority in conventional forces, but instead, could develop the capability to deliver an overwhelming retaliatory nuclear strike anywhere in the world on just a few hours notice.

At the time, the only way to reliably deliver that nuclear strike was by aircraft; first the B-47 Stratojet, then the massive B-52 Stratofortress. But in 1955, the same year the B-52 was put into service, the Soviets introduced the MiG-19, a supersonic fighter capable of intercepting any American bomber. Realizing the problem now at hand, the Air Force issued General Operational Requirement No. 38, calling for a next-generation strategic bomber. After several different design proposals, the contract for this new plane, designated the B-70 and nicknamed the “Valkyrie,” was finally awarded to North American Aviation. The engine contract was given to General Electric.

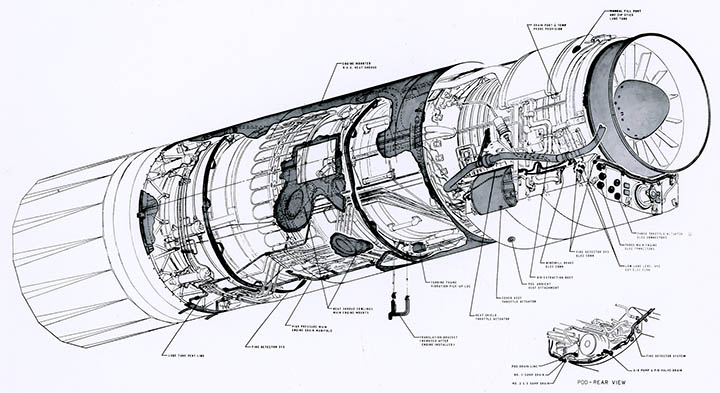

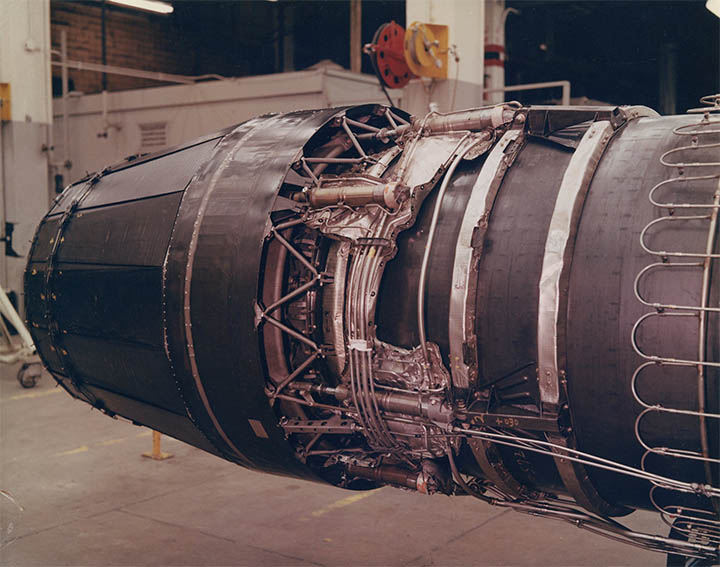

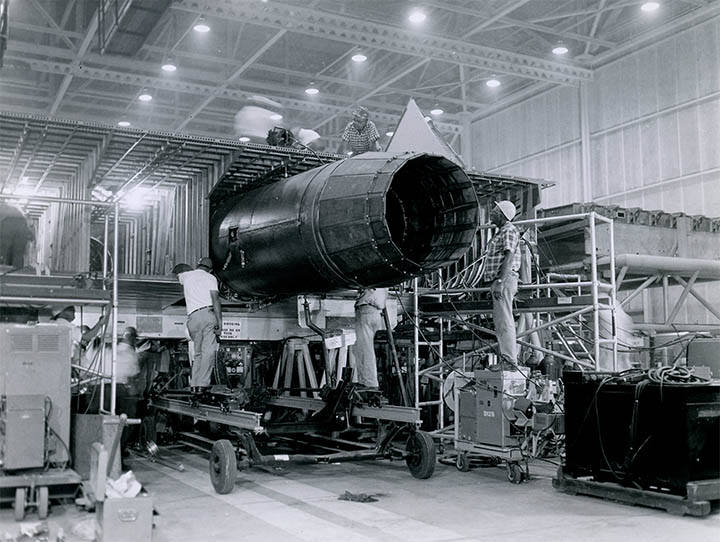

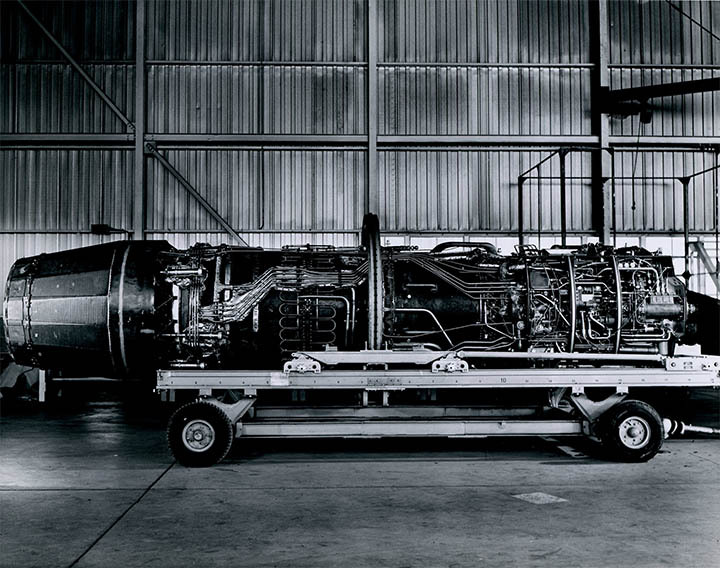

GE was accustomed to adjusting their workforce based on their military and civilian contracts and the XB-70 contract was huge—potentially hundreds of engines. They soon put together a team, including my dad, to design, build and test this new engine-the 30,000-lb class YJ93-3.

Although North American’s chief engineer Harrison Storms was credited with the overall design of the plane—a box fuselage with forward canards and large, foldable wing tips that allowed the plane to literally surf atop its own shockwave—the XB-70 was the result of thousands of nameless engineers and technicians. Among other things, it required new stainless steel-aluminum honeycomb wing and fuselage panels (and new particle-beam welding techniques), more than 200 high-pressure hydraulic devices (including 17 different filters), a novel anti-lock brake system, and even a new type of heat-ablative paint. In all, North American reported that 14 million engineering hours were spent on the project.

Like the airframe, the engine required the efforts of hundreds of engineers to design everything from a new turbofan and compressor, to new fire-suppression systems, to a special high-temperature fuel. Exactly what part my dad worked on is unclear; I always thought it was an oil pan, but my older brother was sure it was an oil pump. Whatever it was, it was a small contribution to something much bigger and something he was always proud of.

III.

After the Soviets tested their first thermonuclear bomb in 1953, Eisenhower made research into missile technology his highest defense priority. Land-based Atlas ICBMs were put into service in 1959 and submarine-based Polaris ICBMs the next year. Missiles were now a much cheaper and more effective way to deliver nuclear weapons than any plane, and the very idea of a supersonic bomber now seemed obsolete. Then, in October 1960, Gary Power’s U2 spy plane was shot down over the Soviet Union and it became clear that no plane, regardless of how fast or high it could fly, was safe from surface-to-air missiles.

During secret meetings in November, 1959, the chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff recommended downsizing the XB-70 to a bare minimum R&D project, but during the 1960 presidential campaign both Kennedy and Nixon supported the XB-70 to court California voters. After Kennedy was elected, however, he again cancelled the project, calling it “unnecessary and economically unjustifiable.” Finally, in March, 1961 a production order for three XB-70s was placed. All of the weapon systems were cancelled and the program was reduced to a study of high-speed aeronautics.

GE delivered the first engines, which included my dad’s oil pan or pump or whatever, in early 1962, but it took North American another two years to complete the first plane: Air Vehicle 1 was delivered on May 7th, 1964 and Air Vehicle 2 five months later. The third plane was cancelled before it was completed.

“14–50. Return to RT Hughes”

Until September 1965 this image was classified by the Dept. of Defense

While congress was debating the future of the B-70 project my parents started a family (older brother, 1960), lived through the Cuban Missile Crisis, bought the only house they ever lived in, experienced the collective shock of the Kennedy Assassination, then watched the Beatles on Ed Sullivan (although they never liked the Beatles; they liked the Irish Rovers and Vivian Della Chiesa). During all of this my dad continued to work on the J93 project during the day and began studying engineering at night. I was born just a week after the first XB-70 was rolled out.

IV.

On September 21st, 1964, AV-1 took its maiden flight from Palmdale to Edwards AFB. One engine failed during the flight and the rear wheels locked on landing, causing a fire. Later problems included honeycomb panels that separated, landing gear that wouldn’t retract, loss of hydraulic pressure and even peeling paint. Eventually the mechanical problems were fixed and the program began achieving its operational goals: the plane reached Mach 1 on October 12th and Mach 2 on March 24th, 1965. Then, on 14 October 14th, 1965—exactly 17 years to the day after Chuck Yeager first broke the sound barrier—it surpassed mach 3. AV-2, an updated design that solved many of the problems with the first airframe, first flew in July, 1965, and eight months later reached Mach 3.08.

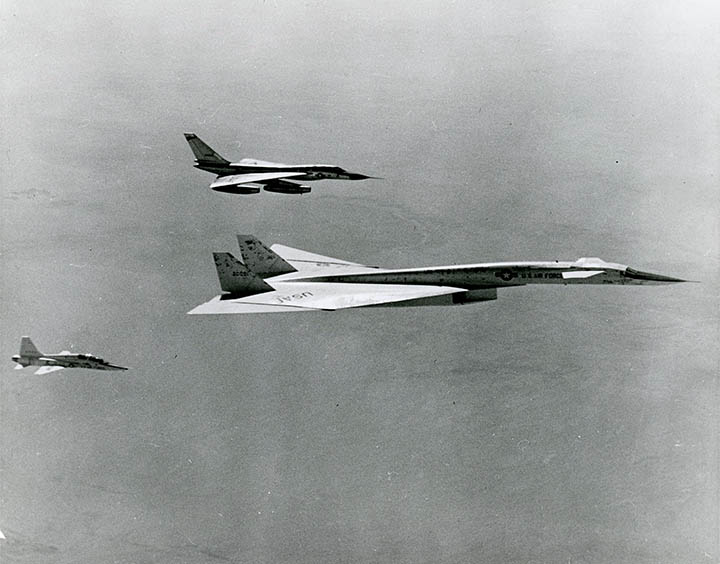

In 1966 the AV-2 was outfitted with sensors for a joint USAF/NASA program to study sonic boom signtures. Then on June 8th, 1966, GE requested a publicity photoshoot of the AV-2 in formation with four other aircraft, all using GE engines. After the photos, an F-104 Starfighter, piloted by NASA’s Joe Walker, collided with the XB-70’s right wing, flipped over and damaged the wing and rear stabilizers on the AV-2 before it went down in a fireball, killing Walker. The AV-2 went into an uncontrollable spin. Pilot Al White managed to eject and survived, albeit with serious injuries, but co-pilot Carl Cross was killed. The AV-2 was destroyed, creating a debris field near Barstow, California.

Despite the loss of the more capable AV-2, the joint test program continued with the AV-1, which was now speed-limited to Mach 2.5. In 1967 the XB-70 was chosen for its last research program—a NASA study of supersonic aircraft control. Finally, on February 4th, 1969, the AV-1 took its last flight from Edwards AFB to Wright-Patterson AFB in Dayton, where it was destined to become a museum piece.

In all, the AV-1 flew 83 test flights and the AV-2 flew 46 flights, for a combined total of 235 hours (including 108 minutes above Mach 3). The Air Force learned that pushing the technological envelope resulted in plane that was difficult to build, difficult to maintain, difficult to fly, and perhaps even more importantly, was incredibly expensive; the program cost nearly 1.5 billion dollars, or around 11 million dollars per flight.

The data from the program, which took years to analyze, was used in the design of the Boeing SST project, the French/British Concorde and the B-1 bomber. The data was even used by the Soviets, through old-fashioned espionage, in the design of the Tu-144.

PN 100265

GE built only 38 engines for the XB-70, and as the project winded down most involved with the engine were reassigned to other projects or were laid off. My dad, however, remained on the J93 project to the very end. He even went to California to watch a test flight. Then, after five years of night school, he finally completed an undergraduate degree in engineering and became the first person on either side of the family to ever graduate from college.

V.

After the J93 project my dad, now a licensed mechanical engineer, worked on a technical manual (a job he hated), then the gas turbine LM2500 engine (a job he liked). Eventually, however, he tired of the constant reassignments and worried about his job security, so in 1972 he left GE to work at Nixon’s newly-created National Institute of Occupational Safety and Health. At the age of 41 he reinvented himself as an industrial hygenist, and became, of all things, an international expert in push-pull ventilation. There’s now even an award given out in his name.

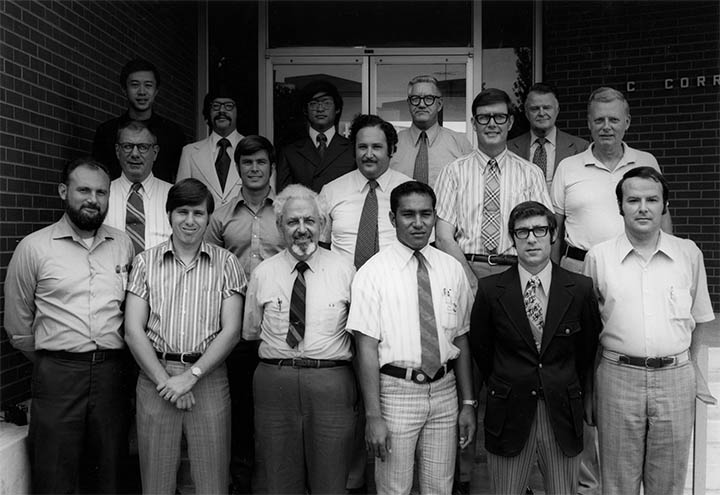

My dad, with his snazzy tie (my daughters’ description, not mine), is in the 2nd row, 2nd from the right

In the early 1990s, when my dad was nearing retirement, we would take a yearly trip to Dayton and the Air Force Museum (usually on the day after Christmas—it became something of a family tradition). In the back hanger was the only remaining XB-70, a monster dwarfing the aircraft displayed around it. My dad would point to the engine on a yellow dolly under the wing and said to his grandsons, “You know I worked on that, right?”

Although my dad didn’t live long enough to see it, he now has great-grandchildren. In a few years—when their old enough to understand—I’ll take them to the Air Force Museum (hopefully on the day after Christmas), show them the engine under the XB-70 and tell them the story of their great-grandpa.

—February 5th, 2019. Photography