The Steamboat and the Cornfield

The Saga of the Virginia

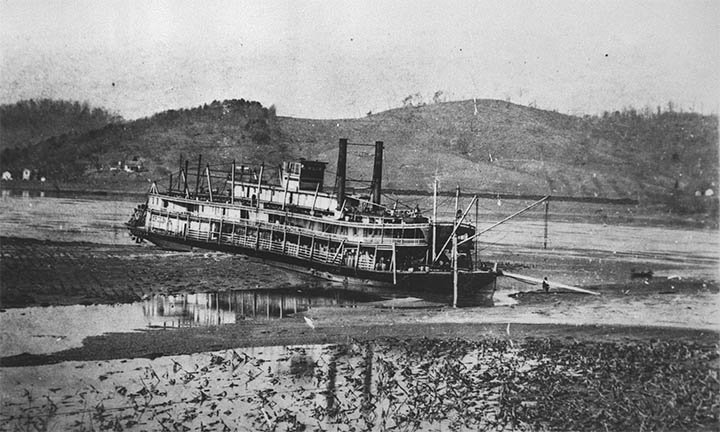

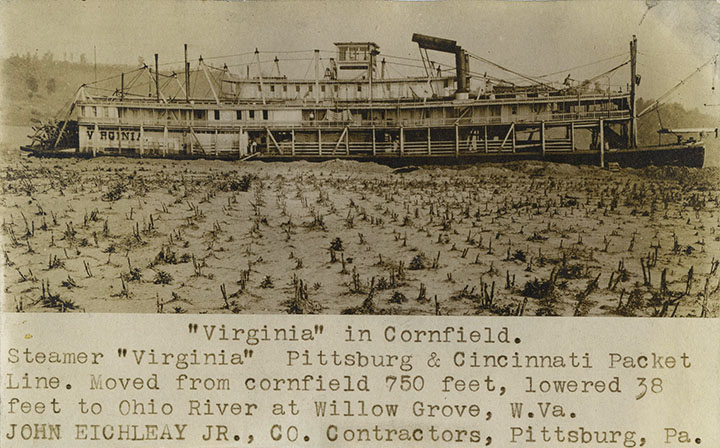

On the first Sabbath after the Virginia had grounded—March 13th, 1910—the packet boat Tacoma ran a special charter from Gallipolis and Point Pleasant to the Williamson’s family farm in Willow Grove, where the Virginia lay bowed in their cornfield. Some 300 excursionists, dressed in their Sunday best, made an afternoon of it, viewing the massive spectacle and enjoying the unseasonably warm, but windy weather. While his passengers were milling about, Jesse Hughes, the captain of the Tacoma, took this photo from his pilothouse on the shore of the Ohio River, some 700 feet away.

The Tacoma was by no means the only boat to visit what the Point Pleasant Register called “a cornfield decoration.” The Bessie Smith lead an excursion out of Marietta with several hundred passengers who had a picnic lunch in the field. On Easter Sunday the Jewel came down river from St. Marys with the town’s brass band. Later the Valley Belle arrived from Pomeroy, the Klondike from Syracuse and the W. O. Hughart from Racine. The B&O Railroad (whose track is visible on the ridge in the photo) even added extra coaches to their local trains for sightseeing trips.

If you were anywhere near Willow Grove, West Virginia, that spring and summer, going out to see the stranded Virginia was apparently the thing to do.

I.

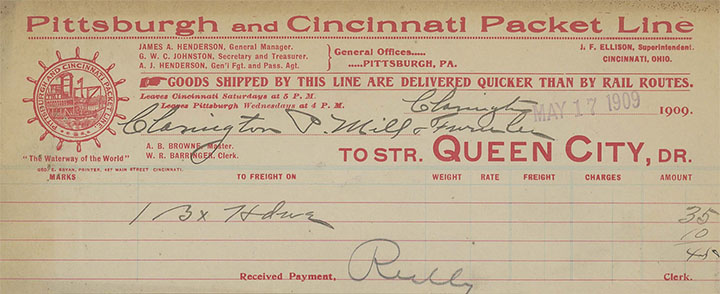

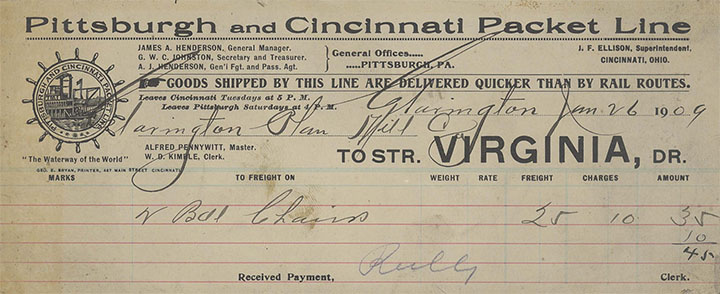

In 1877, Jackman Taylor Stockdale, who began his career on the river as a clerk on the American in 1845, and his nephew, Thomas Stevenson Calhoon, who first worked on the Metropolis in 1856, decided to join forces and organized the Pittsburgh and Cincinnati Packet Line. Stockdale acted as the general manager while Calhoon captained their flagships: first the Katie Stockdale (1877, named after Stockdale’s youngest daughter), then the Keystone State (1889) and the Iron Queen (1892). After a fire destroyed the Iron Queen in April, 1895, they decided to replace it with not one, but two new flagships.

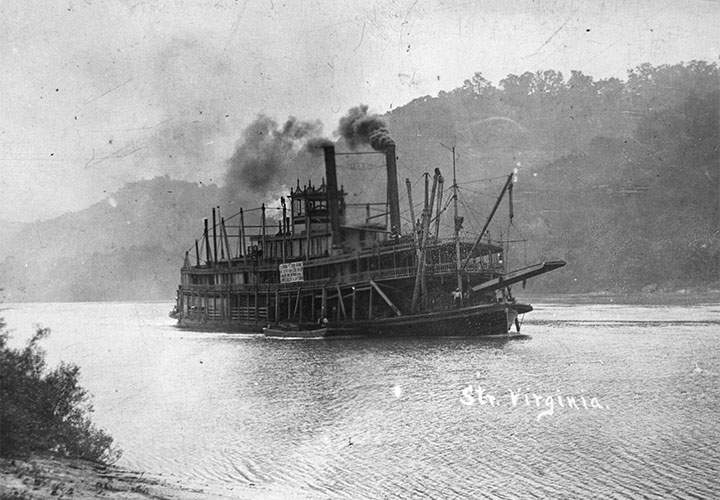

The first of these new boats, The 42,000 dollar, 230-foot Virginia, built by the Cincinnati Marine Railway Company, was framed in oak, sided in pine and had an innovative set of hog chains and trusses to keep it from bowing. The boilers and condensing engines, supplied by Griffith and Wedge of Zanesville, could drive the sternwheel at thirty revolutions per minute, which, as one reporter noted, was “several more than the average.” Another engine powered a generator, from General Electric of Schenectady, which supplied electricity for incandescent lighting in the cabin and staterooms as well as a carbon-arc searchlight on the bow.

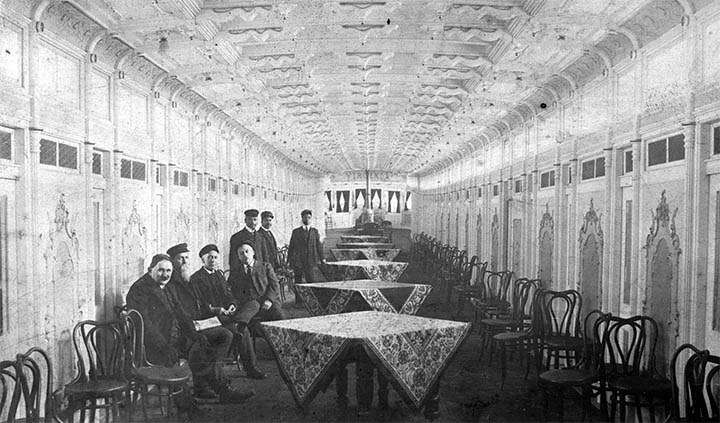

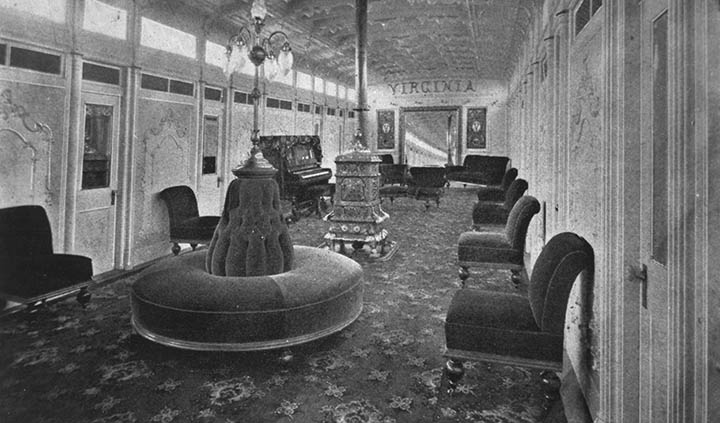

No expense was spared with the Virginia’s appointments. The main cabin, which could seat 120 for dinner service, included blue floral carpet, fancy embossed wallpaper and a carved wooden ceiling. The ladies cabin included velvet settees and easy chairs, as well as an upright piano. Each of the 60 staterooms had bevelled-glass mirrors and double berths with fine linens supplied by Joseph Horne of Pittsburgh. “The outlay in this department alone exceeds the entire cost of old-time steamers,” they claimed in their promotional brochure.

Murphy Library Special Collections, University of Wisconsin-La Crosse.

Murphy Library Special Collections, University of Wisconsin-La Crosse.

On December 30th, 1896 the Virginia was launched from the wharf at the foot of Broadway in Cincinnati. On its maiden voyage up the Ohio it attracted crowds in every port and even received a cannon salute in Huntington. Upon its arrival in Pittsburgh, a formal ball was held in the cabin. “The new Virginia eclipses any other steamer that has plied the Ohio,” said one Pittsburgh daily. “It is the finest river parlor on western waters, without doubt,” wrote the Wheeling Daily Intelligencer, “Hundreds of electric lights combine to make the cabin a dream of beauty at night.”

The Virginia, and the equally opulent Queen City, launched in 1897, soon became the most profitable boats on the Ohio, transporting cargo from nearly every town on the river and drawing their passenger lists from the social registers of Pittsburgh, Wheeling and Cincinnati.

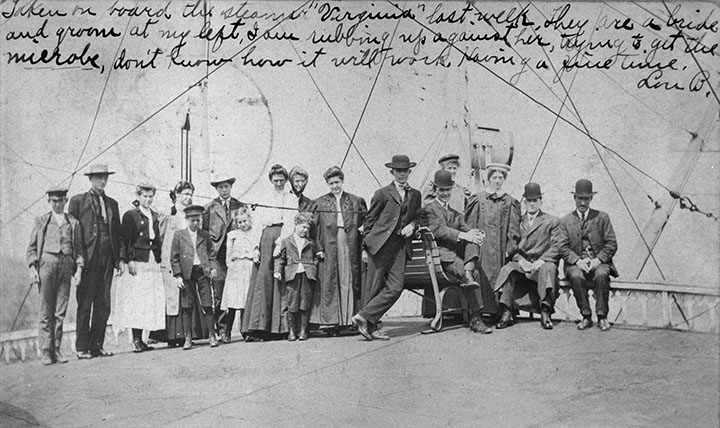

Murphy Library Special Collections, University of Wisconsin-La Crosse.

Stockdale died unexpectedly on June 8th, 1897, at the age of 59, and his Pittsburgh agent, James Henderson, bought a controlling interest in the line. Captain Jim, as he was known, also had a long career on the river and by the time he took over he knew how to run a packet line. Henderson, however, was facing a much more difficult environment than Stockdale had two decades earlier. Not only was he trying to compete with other lines on the Upper Ohio, but with the rapidly expanding railroads and their growing network of river terminals. Eventually the railroads, with the help of Congress, prevailed and in November, 1909, Henderson was forced to put the company into receivership.

II.

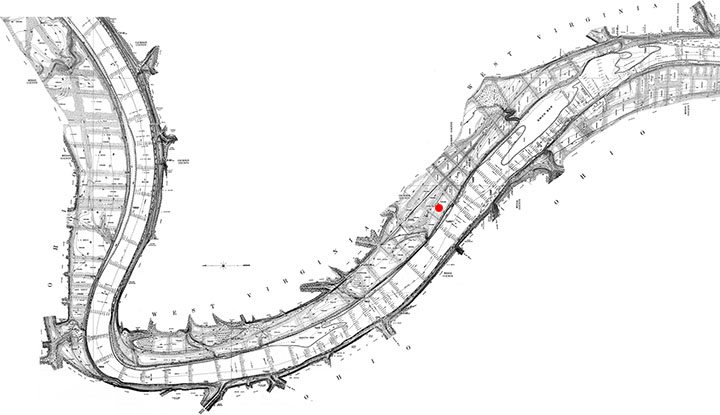

From its origin at the confluence of the Allegheny and Monongahela rivers until it empties into the Mississippi, the Ohio River—named after the Iroquoian Ohi’yó (“Good River”)—is 981 miles long, drops some 440 feet, and has enough snags, gravel beds and sandbars to test the abilities of even the most seasoned pilots. Historically, the river became too shallow for all but the smallest packet boats to navigate by mid-summer and didn’t rise again until the rains of November and December. By January and February, winter rains and snow melt would swell the river and its tributaries, often past flood stage. One 19th-century newspaper said that no river in America varied so widely.

In early July, 1909, as expected, the river dropped below packet stage and the Line’s boats had to lay up for the summer; the Queen City in Pittsburgh and the Virginia in Cincinnati. But that year the autumn rains and the rise in the river never came. Then the December rise never came and by the New Year Henderson’s fleet was still laid up. For a company in receivership, this was, obviously, something a problem.

By late January the river had finally rose and the Queen City left for is annual trip to Mardi Gras. The expected profit of 20,000 dollars was, now more than ever, critical to the Line. The trip, however, was disastrous. The boat grounded on a sandbar on the lower Mississippi and it took a lighthouse tender 40 hours to free it, straining the hull in the process. The Queen City didn’t reach New Orleans until February 7th, just a day before Fat Tuesday. On the return trip the boat was buffeted by ice and had to lay up below St. Louis. By the time it arrived in Cincinnati, with the bilge pumps running continuously, the hull was so badly damaged that officials pulled its inspection certificate.

Henderson ordered the docked Virginia to steam up and continue the trip to Pittsburgh. While transferring the passengers, Eugene Campbell, the second engineer on the Virginia, noticed two cross-eyed gentleman boarding, which, according to old rivermen superstitions, was considered an ominous sign. He was sure they had “jinx’d” the Queen City and now were going to bring bad luck the Virginia.

III.

Because of the rising river, the Virginia didn't make it to Pittsburgh until March 4th—a week-long trip that normally took three days. With the Queen City now waiting for repairs and creditors nipping at his heels, Henderson made the decision to put the Virginia back into its regular service immediately. The boat was loaded with its heaviest cargo in years—nearly 600 tons by one account—and had some 50 passengers, including dockhands bound for laid up tugboats in Middleport. Some time just after midnight, Saturday, April 5th, it left the Wood Street wharf where the river was now falling.

Although the Ohio was receding in Pittsburgh, the Virginia would now be chasing the crest of the floodwaters down the river. Fortunately, Henderson had an expert crew on board. The captain was Charles Knox and the pilot was Billy Anderson, both from the line’s Keystone State. Henderson also recruited the legendary Tony Meldahl, who had previously been a pilot on the Queen City, to be the de facto chief navigator. Together the trio had nearly 100 years of experience on the river.

By four in the afternoon that Saturday the Virginia had reached Marietta at mile 172, where the river crested above flood stage the day before. At mile 184 it arrived at Parkersburg where, according to reports, it did “considerable business.” By the time the Virginia left is was now dark, and using the searchlight in increasingly high waters, Anderson navigated the boat through a difficult meander to Ravenswood at mile 220, where purser Clyde Packard registered a passenger who paid a 50-cent fare for a trip to Willow Grove, just seven miles up river.

Due to the river conditions, Meldahl recommended that the Virginia tie up for the night but by now captain Knox had a new, and vexing problem. The boat didn’t have a bar, but that didn't stop the Pittsburgh deckhands from bringing their own whiskey on board, and instead of sleeping, they were “whooping it up.” Knox was noted for his abstinence and he wanted these drunks off his boat before they caused any damage. After a discussion in the pilothouse, it was decided to reverse course, head upriver to Willow Grove, then continue downriver to Middleport.

Despite the the government navigation lights being flooded out and the river now resembling a giant, very dark lake, Anderson managed to pilot the Virginia to the landing in Willow Grove. He floated the boat over what was normally dry land and discharged the single passenger and a few barrels of cargo for the general store. The Virginia was now facing upstream and Knox thought that if they took it easy the boat would likely float itself out to the channel, so Anderson set the rudder and rang back slow to the engineer. They expected the stern to move towards the channel but instead the boat was carried by the current into the field and after a grating sound under its hull the Virginia came to an abrupt stop. The crew jettisoned some of the cargo, including spools of barbed wire, and tried pushing off with the spars, but, despite their every effort, the boat wouldn't budge.

USACE Digital Library

By daybreak Sunday morning—March 6th—the towboat Volcano arrived and tried to jerk the Virginia free. However, after snapping a few towlines, they gave up. The passengers—including the now hung-over deckhands—were fed breakfast then transported by flatboats to dry land to catch the morning B&O train. Later that afternoon one of the Virginia’s hogchains broke and the boat bowed over a hump in Williamson’s cornfield as the water began to receed.

IV.

Soon the newspapers began reporting the story. “One Dead in Steamer Wreck—Pilot Mistakes House Light for Signal and Runs into Cornfield,” was the headline in the Pittsburgh Gazette-Times. “Steamer Virginia—Hard Aground at Willow Grove—is Said to be Breaking in Two,” wrote the Point Pleasant Register. “The Virginia Will be a Total Loss,” said the Marietta Daily Times. Although the accounts in the papers were wildly inaccurate, the publicity attracted throngs of sightseers to Williamson’s farm—nearly 1000 that first Sunday alone.

Murphy Library Special Collections, University of Wisconsin-La Crosse.

Murphy Library Special Collections, University of Wisconsin-La Crosse.

Murphy Library Special Collections, University of Wisconsin-La Crosse.

Murphy Library Special Collections, University of Wisconsin-La Crosse.

Henderson arrived from Pittsburgh on Tuesday, March 8th, just as the cornfield was drying out, and took up residence on the Virginia. He ordered the remaining cargo—hundreds of barrels of queensware china—transferred to other boats and contracted with the Kanawha Dock Company of Parkersburg to block up the hull before it did split in two. Another flood that could float the boat out to the river was now unlikely this season, so Henderson asked the Eichleay Company of Pittsburgh to move the boat back to the river.

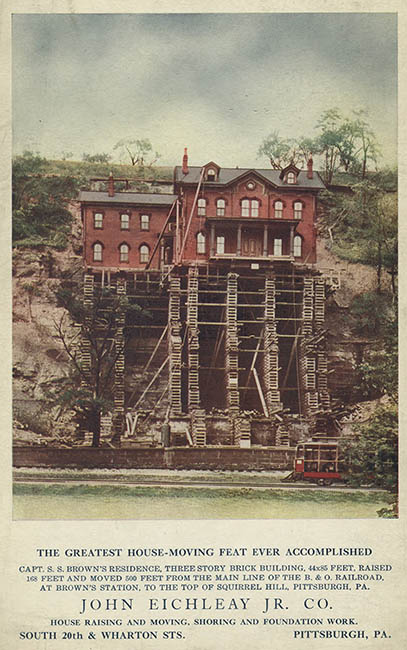

The John Eichleay, Jr. Company had earned a reputation for being able to move anything. In 1903 they famously moved Captain S. S. Brown’s palatial 24-room mansion 168 feet up the side of a sheer cliff then back another 500 feet. It was, as they advertised, “The greatest house-moving feat ever accomplished.” Near the end of the month they loaded the Greendale with timbers, rollers and jacks and set off for Willow Grove.

Murphy Library Special Collections, University of Wisconsin-La Crosse.

Eichleay’s plan was to excavate under the boat, build cradles and place rollers under the hull, dig a trench through the cornfield, and pull the 600-ton boat along a wooden track to the river. But as his crews started digging, they began unearthing curious artifacts under the boat. Henderson contacted several experts and Henry Shetrone, an archeologist from Ohio State, determined that the finds were likely from the Adena or Hopewell. It appears that the Virginia had run afoul of an ancient Indian burial mound.

If the Indian mound wasn’t enough, Eichleay’s crews also dug up several skeletons in shallow graves. They were thought to be a group of Virginia militia officers killed by the Shawnee or Mingo as they retreated north after the Battle of Point Pleasant in October, 1774. Perhaps the Virginia was indeed “jinx’d” by the crosseyed passengers in Cincinnati, or perhaps it was cursed by the Shawnee chief Cornstalk, who, while on a mission seeking peace with the Virginians in 1777, was executed along with his son at Fort Randolph and reportedly said with his dying breath “You have murdered, by my side, my young son... For this, may the curse of the Great Spirit rest upon this land.”

Henderson held court with reporters and sightseers from the deck of his grounded boat. Despite the circumstances, he seemed to be enjoying the attention and publicity. James Williamson, however, wasn’t enjoying having his field dug up. He demanded a payment of 500 dollars, and being a practical farmer, refused Henderson’s check and insisted on cash.

While the Virginia was stranded in Williamson’s field, Calhoon, the long-time captain of the boat, who retired in 1904, died at the age of 75 in his Georgetown home. A week later Halley’s Comet made its first appearance in the early morning sky over Willow Grove.

Despite the archeological setbacks, the Shawnee curses and Williamson’s objections, work in the cornfield continued and soon Eichleay’s crews had dug a trench to the river. Using teams of horses—12 teams in all—they began moving the boat at 20 feet per hour and within a few days had pulled the Virginia to the river. At the bank, however, the soft sandy soil gave way and the boat sunk into the ground, precariously lodged above the river. Eichleay told Henderson that, with additional money, he could erect pilings and lower the boat into the water, but more money was something Henderson simply didn’t have.

Murphy Library Special Collections, University of Wisconsin-La Crosse.

The Virginia stayed on the bank for the rest of spring. Then, in mid June, rain began swelling the river and Henderson, now back in Pittsburgh, wired Knox and ordered him back to Willow Grove. Finally, on the morning of June 20th, the water rose to meet the boat and Knox floated it back into the river. On June 27th, the Virginia arrived back in Pittsburgh. Tugs and steamers blew their whistles and rang their bells. Curious onlookers lined the wharf. It was the boat’s greatest reception since its maiden voyage, some 14 years earlier. The Virginia was now back in service.

Str. Virginia. Pittsburgh Cincinnati Packet Line. Moved from Cornfield 750' Lowered 38'

Toward River at Willow Grove W. Va. by John Eichleay Jr. Co. Pittsburgh Pa.

Murphy Library Special Collections, University of Wisconsin-La Crosse.

Then, not two weeks later, because of the falling river, it had to tie up for the summer.

V.

In a Pittsburgh courtroom Eichleay confronted Henderson, who had refused to pay the 2900-dollar bill, claiming Eichleay did not fulfill his contract and that the Virginia was returned to the river by “an act of God.” The judge disagreed, stating that “it may have been an act of God, but Eichleay had placed the boat within God’s reach.”

However, it’s unlikely that Eichleay ever saw any of the money he was due. By this time the line was insolvent, and after several attempts at a sale, the assets were purchased for around 20 cents on the dollar by the Pittsburgh industrialist John Hubbard. who formed the Ohio and Mississippi Navigation Company and renamed the Virginia the Steel City. In 1914, Hubbard, who had interests in several packet and railroad lines, sold the Steel City where it entered the St. Louis–New Orleans trade on the Mississippi, transporting baking soda south and molasses and sugar north. It was renamed the East St. Louis in late 1916, and with new owners, was turned into an excursion boat in May, 1918.

Herman T. Pott National Inland Waterways Library at the University of Missouri - St. Louis

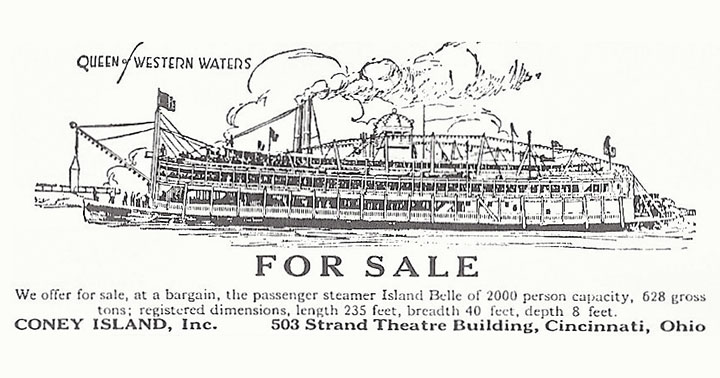

In 1923 the Coney Island Company of Cincinnati bought the East St. Louis and renamed it the Island Belle. Four years later, realizing they needed a bigger boat, they put it up for sale.

The Greater New Orleans Amusement Company bought the Island Belle and renamed it the Greater New Orleans. It was finally dismantled in St. Louis in 1930. Frederick Way wrote that the typical lifespan of a steamboat was around 20 years—about the same as a workhorse, but the Virginia had lasted 35 years on the inland rivers. A charmed life, all considering.

That should be the end of the story of the Virginia, but in 1975 the the New Orleans Steamboat Company built the Natchez, a nearly exact, albeit updated, replica. The Natchez still offers excursions from its Toulouse Street wharf.

Since Major Stephen Long first built a wing dam near Henderson in 1829, generations of people have tried to tame the Ohio. A series of 51 wicket dams were built by the Army Corps of Engineers in the 1920s and then replaced by 21 fixed dams and locks (including one named after Tony Mehdahl) in the 1960s and 70s. This last project created a series of navigation pools and 24-foot deep slack-water channels allowing year-round navigation for coal and grain barges, or, for that matter, the occasional excursion boat. All of this civil engineering, however, is powerless against the high waters of winter. In Cincinnati, where I live, the river has reached flood stage 105 times since records began in 1858—the last time being in February of this year. It’s a never-ending cycle known all too well by those who live near its banks.

—July 23rd, 2018. Updated July 31st, 2018. Photography