127

De Evangelica Praeparatione

Nicholas Jenson and the Humanist Letter

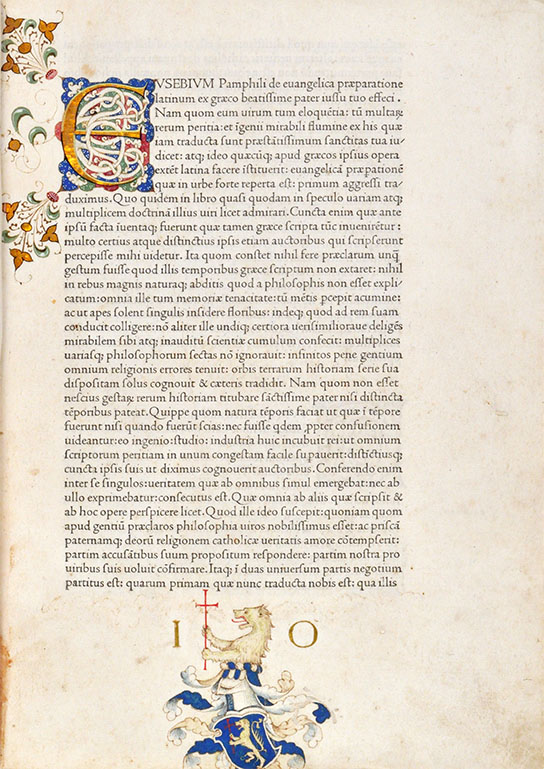

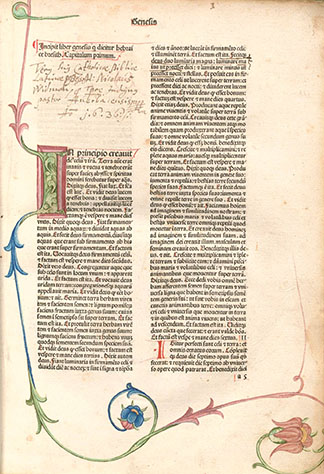

Here is the first page of Eusebuis’ De Evangelica Praeparatione.1 The book, printed in 1470 by Nicholas Jenson, was perhaps the first appearance of a completely considered humanist Roman typeface based entirely on contemporary calligraphy.

The illumination, done by an unknown artist, is thought to have been for Joannes Simonetta, ducal secretary of Francesco Sforza. It is one of a number of illustrated de luxe versions of the book. Here are a few more examples:

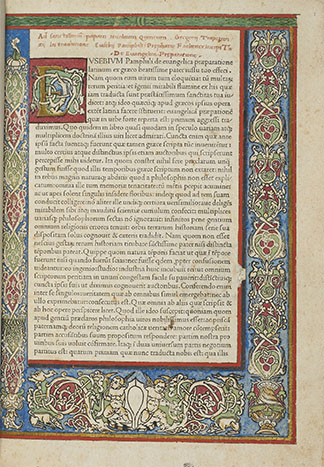

Printed border. John Rylands Library

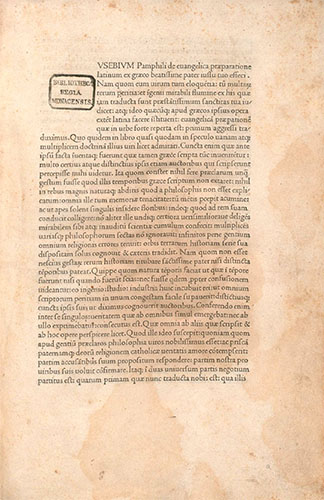

No border. Bayerische StaatsBiblothek

Nicholas Jenson was born in 1420 in Sommevoire, France to Jacob Jenson.2 He was apprenticed as an engraver and was eventually promoted to the Master of the Monnaie du roi à Tour. On 4 Oct 1458, King Charles VII send him to Mainz to study printing and “achieve a new understanding of the art and of execution thereon for the kingdom of France.”

Jenson spent nearly three years in Mainz, possibly studying under Schoffer and Fust. He returned to Paris after the sack of Mainz, but the new monarch, Charles’ son Louis XI, didn’t share his fathers enthusiasm for printing and by 1468 Jenson was in Venice where he apparently worked at the press of Johannas de Spira.

Ars Grammatica, which includes Jenson's Greek type, ca.1475. Bayerische StaatsBiblothek

Biblia Latina, showing Jenson's gothic type, 1476. Bayerische StaatsBiblothek

After de Spira’s death in 1469 Jenson opened his own printing office in San Salvador and over the next decade became the most successful printer in Venice. Indeed, his operation was nearly industrial. He employed a group of artists to illuminate de luxe copies of his books and by 1477 his shop was reportedly operating 12 presses. He even received the patronage of Sixtus VI in 1475.

Aside from the De Evangelica, other notable titles included Cicero’s Rhetorica (1470), Pliny’s Historia naturalis, (1472 and 1476), Sallustius’ Opera (1474). He also printed a number of ecclesiastical and canon law books. According to Lowry, between 1470–1480, he printed 108 editions.

In addition to being a successful printer, Jenson was also an astute businessman. He formed the book-trading partnerships Nicolaus Jenson sociique in 1475 and Johannes de Colonia, Nicolaus Jenson et socii in 1480. He died a wealthy man in Oct 1480.3

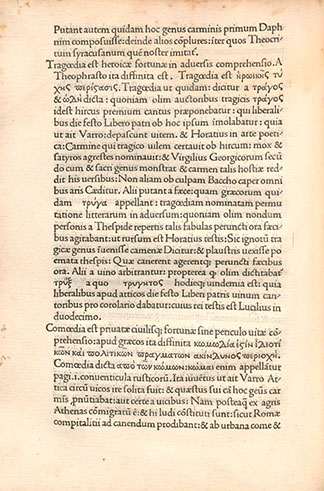

By the 15th century Italian humanist scribes, such as Poggio Bracciolini, Niccolò Niccoli and Bartolomeo Sanvito had developed bookhands based not on the prevailing gothic but on ancient Roman inscriptions and Carolingian minuscules – the lettera antica. Jenson modelled his 76-character, ~16pt design on the upright versions of these scripts.

His type had a relatively low contrast in moduation with a right-handed axis, open counters, nearly circular bowls and a small x-height.

It was the most legible and elegant face of it’s day. As Jenson’s partners wrote a 1482 ad: “[Jenson’s books] do not hinder one’s eyes, but rather help them and do them good. Moreover, the characters are so intelligently and carefully elaborated that the letters are neither smaller, larger nor thicker than reason or pleasure demand.”

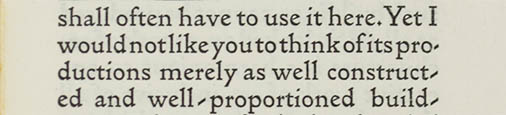

Jenson's work was resurrected by the early 20th century arts-and-crafts designers. William Morris’ Golden Type for Kelmsicott Press was a darker version of Jenson's 1470 design:

Gothic Architecture, Kelmscott Press, 1893. Heritage Book Shop

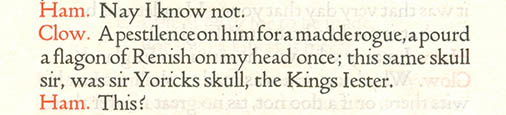

Doves Press founder Thomas James Cobden-Sanderson collaborated with the engraver Emery Walker to produce the excellent Jenson-inspired Doves type:

The tragicall historie of Hamlet, Prince of Denmarke, Doves Press, 1909. SCOLAR

Perhaps the best Jenson revival was Bruce Rogers’ Centaur from 1915:4

An Account of the Making of the Oxford Lectern Bible, 1936

1. Eusebius Caesariensis, trans: Georgius Trapezuntius, with additions by Antonio Cornazzano. De evangelica praeparatione. Venice: Nicolaus Jenson, 1470. [ITSC: IE00118000]. The book consisted of 142 f° sized (22.7 × 34.25 cm) folios. The first page was printed both with and without a border and their are a number of illuminated versions done by both Jenson’s artists or by private commission.

2. For more about Jenson’s life and career see: Lowry, Martin. Nicholas Jenson and the Rise of Venetian Publishing in Renaissance Europe. Oxford: Blackwell, 1991.

3. Like thousands of ducats rich. See: The Last Will and Testament of the Late Nicolas Jenson. Chicago: Ludlow Typograph Co, 1928. An english translation of the will is online. Jenson bequeathed his punches and matrices to Peter Ugelleymer, his partner in Nicolaus Jenson sociique. Ugelleymer subsequently sold them to the printer Andrea dei Toressani, who would become the father-in-law of Aldus Manutius.

4. For more on Centaur see: Rogers, Bruce. The Centaur Types. Chicago: October House Press, 1949.

11 Aug 2012 ‧ Typographia Historia