Codex xcix ‧ 6

A Severely Attenuated History of the Alphabet

After the near simultaneous appearance of Sumerian cuneiform and Egyptian hieroglyphic, the rebus principle and written language diffused throughout nearby civilizations. Over the next 1500 years scripts appeared as far north as Anatolia, east to the Iranian plateau and the Indus River valley, and West to Minoan Crete.1

For our purposes let’s trace the spread of Egyptian hieroglyphs. This first jump is, admittedly, somewhat speculative, but by 1900 BC simplified versions of single-sound hieratic characters appeared in Egypt, Sinai and the Levant. These signs were likely used to allow Egyptians to communicate with the Semitic-speaking peoples of the Sinai and the Levant, who at times were slaves, mercenaries or trading partners with Egypt.

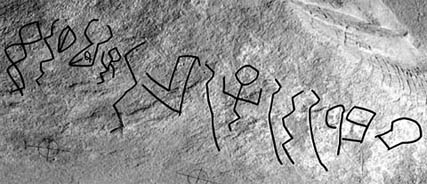

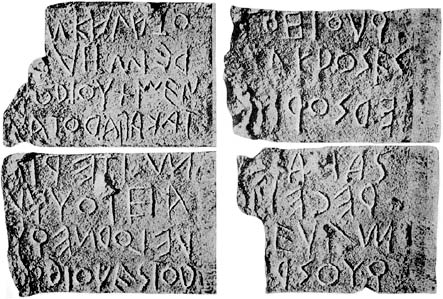

The Proto-Sinaitic Wadi al-Hol inscriptions, ca.1900 BC. From Wikipedia.

The script, called proto-Sinaitic, consisted of 28 different signs; one for each consonantal sound of their Semitic language.2 The Canaanites, and later the Phoenicians (who were themselves Canaanites) adopted the script.3

The Phoenician Ahiram sarcophagus inscription, ca.1000 BC.

The Phoenicians, with city-states in Tyre, Byblios and Sidon, became a major power sometime around 1200 BC. They began extensive maritime trade, initially with Greece, their neighbor the the west. Herodotus, in his Histories, describes the Phoenicians as “freighting their vessels with the wares of Egypt and Assyria…”, but perhaps their most important export was Tyrian Purple, a red-purple dye, highly prized by the Greeks, and later by the Romans.4 Over time the Phoenicians expanded their trading throughout the Mediterranean, establishing posts in Carthage and, eventually, as far west as Morocco. Naturally their written “alphabet” was also spread throughout the Mediterranean and was adopted by many different civilizations in one form or another. Phoenician became the basis of nearly every modern written language.5 It was the Mother of all Alphabets.

The Greeks were among the first to adopt the Phoenician alphabet. According to Herodotus (again from his Histories), Prince Cadmus brought the Phoenician alphabet (phoinikeia grammata) to Euboa in 776 BC, although current research suggest an earlier date, perhaps as early as 900 BC. Early Greek directly borrowed the Phoenician letters, but because it was very different from the Semitic languages, with many words that began with vowel sounds, the Greeks adapted some of the original Phonecian consonantal letters to represent their vowels and created the first true alphabet.

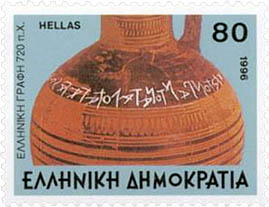

The Greek Dipylon inscription, ca.720 BC.

Over the next few hundred years different variants were developed in Ionia, Athens, Corinth, Argos, and Euboa. This disparate state of affairs continued until 403 BC when Athens decreed that the Ionic variant was the official script of all of Greece.6 It is this version that is, essentially, modern-day Greek.

But to back up for a minute. In the eighth century BC, during the period known as the Magna Graecia, Greeks colonized several foreign lands, including the eastern coast of the Black Sea, Massalia, and the southern part of the Italic peninsula. Around 750 BC, the Etruscans, then the dominant culture on the Italic peninsula, adopted the Euboan alphabet of the southern Greek settlers. Little is known about the Etruscans but surviving funerary inscriptions suggest that they adopted 20 of the Greek symbols for their own spoken language.

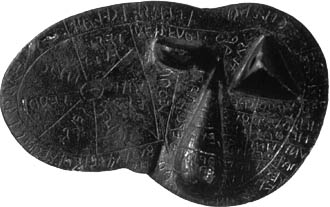

The Etruscan Liver of Piacenza, ca.250 BC.

The Etruscan alphabet, was in turn adopted by other Italic civilizations, including the Latini, Osci, Sabini, Umbri, and Veneti. These alphabets are known collectively as Old Italic.

According to legend the Latin city of Rome was established on 21 April 753 BC by the twin brothers Romulus and Remus, and by 650 BC they had adopted 21 of the 26 Etruscan letters for their own language.7 The Latini formed the Roman Republic around 509 BC and eventually conquered the tribes of Italy, first the Sabines, then the Etruscans, and later spread their dominance throughout the Mediterranean. By the time of the Roman Empire (ca. 44 BC), their control stretched as far west as Hispania, as far north as Britannia, as far south as Egypt and as far east as Persia.

The Latin Lapis Niger inscription, detail, ca.600 BC.

It was also around this time that classical Latin literature reached its zenith, with works such as Lucretius’ De Rerum Natura, Virgil’s Aeneid, Plyny the Elder’s Naturalis Historia, Cicero’s De Re Publica, Caesars’s Commentarii de Bello Gallico, or Vitruvius’ De architectura, to note just a few examples.

Although the golden age of Latin literature ended around the first century AD, Latin continued to be written and spoke throughout Europe. After the fall of the Roman Empire on 4 Sept 476 AD, it continued to be the language of the Holy Roman Empire.8 By the eighth century AD it had mostly been replaced in Italy, France and Spain by the rapidly evolving Romance languages. The use of classical Latin picked up again after the Carolingian Reform around 800-900 AD and Latin continued to be the lingua franca of the educated classes throughout the middle ages, and of the humanist scholars during the Renaissance. Nearly all of the important literature, particularly scientific literature, of the Renaissance was written in classical Latin.

Over the intervening years Latin again fell out of favor, largely due to the unrelenting spread of English. Today it still is widely studied but rarely spoken. It does, however form the root of most Western languages and still appears in a surprising number of ways.9

1. Written scripts appeared independently in the Yellow River Valley (ca.1200 BC), and much later (ca.500 BC), in Mesoamerica.

2. Because the Semitic language had no vowels (these had to be supplied by the speaker) it is technically a consonantary or consonantal alphabet, also known as an abjad. The use of written vowels, and a true alphabet, would take another millennia. See: Gardiner, Sir Alan H. The Egyptian Origin of the Semitic Alphabet. Journal of Egyptian Archaeology 1916(3): 1-16.

3. Proto-Canaanite or Old Canaanite directly evolved into Phoenician. Scholars consider this, for the sake of convenience, to have occurred in 1050 BC.

4. Phonecian, in fact, comes from the Greek word Φοινίκη (Phoiníkē, purple). Tyrian purple, also known as royal purple or imperial purple, is a dye from hypobranchial gland excretions of the gastropod Murex brandaris. The main component being 6,6′-dibromoindigo [CAS 17670-06-3]. The Phoenicians developed Tyrian purple facilities in Tyre (hence the name), and later, in Mogador, Morocco. Litle is known about the exact production methods, but apparently, the snails were gathered in large vats and left to decompose, leaving a hideous stench, a fact mentioned by ancient authors. Later the plant dye indigotin (2,2’-Bis(2,3-dihydro-3-oxoindolyliden)) [CAS 482-89-3], from the genus Indigofera became the primary source for indigo. In 1897 Adolph von Baeyer developed the first synthetic process for indigo (for which he was awarded the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1905). Today, virtually all indigo is synthetic and the large majority of that is used to dye cotton for denim jeans. It should be noted, however, that Tyrian purple has never been synthesized in commercial quantities and is still considered superior to the plant-based or synthetic dyes.

5. Again, that damn Chinese script, and its Japanese progeny, are the exception.

6. Ionic was likely chosen because Homers Ἰλιάς (iliás, Iliad) and Ὀδύσσεια (Odússeia, Odyssey) were originally written in Ionic Greek.

7. The original Latin alphabet consisted of 21 letters. Around the third century BC the letter Z, an unused holdover from Etruscan, was replaced by the letter G. After the conquest of Greece in the first century BC, Latin adopted the Greek letters Y and Z to accommodate new Greek loanwords. The Emperor Claudius attempted to add three new letters during his reign; a reversed C (antisigma for /bs/ or /ps/), a turned F (digamma inversum for /w/ or /v/) and a half H (for /y/), But the Claudian letters did not last beyond his death (by poisoning, of course) in 54 AD. Thus Latin ended up with 23 letters.

8. Latin was the official language of the Catholic liturgy until the Sacrosanctum Concilium on 4 Dec 1963, and Latin is still the official language of the Holy See, but Italian is the official language of the Vatican City.

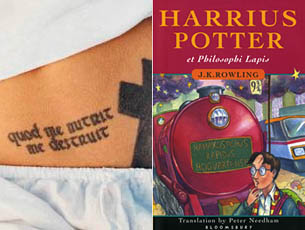

9. E.g. Angelina Jolie, in extreme detail (and be thankful that it’s not Brittany), and J.K. Rowling, in translation:

6 Nov 2008 ‧ Typographia Historia