This painting by Pierre-Auguste Renoir, composed en plein air, depicted the Sunday dances at Le Moulin de la Galette and was painted "not without some difficulty" in May 1876. The image, which included both regular patrons and some of Renoir's preferred models, was intended as an experiment in natural, tree-dappled light.1 When it was first shown at the Third Impressionists Exhibition in 1877 it received mixed reviews, however Sotheby's sold a second, smaller version of the painting for 78 million USD in 1990. So there's that.

Near the top of butte Montmartre the Moulin (mill) Blute-fin, built in 1616, and the adjacent Moulin Radet, built in 1717, became known for milling rye and baking a small, flat bread called a galette. These galettes, served with milk, became rather popular with the locals.

In 1809 the two mills were bought by Nicolas-Charles Debray. Legend has it that on 30 March 1814, during the capitulation of Paris, the four Debray brothers defended the mill against the advancing Cossacks. Three of the brothers were killed and the eldest, Pierre-Charles, was even dismembered and hung from the vanes of the windmill.2 Charles-Nicholas, the sole surviving son, replaced the milk they served with the local muscatel and opened a guinguette in 1830. An open air dance hall was added in the 1850s and later a fully enclosed cabaret.

Dave Hughes, Montmarte/Sacré-Coeur from the Orsay, 3 Oct 2014

The relaxed atmosphere of the Sunday dances (3 p.m. to midnight) at the Moulin de la Galette gave the working-classes of Northern Paris a chance to dress up and forget their workaday lives. A brass band played quadrilles, polkas and waltzes, and as the night drew late even the can-can. The Moulin also attracted slumming bourgeois men, hoping for easy women as well as prostitutes and their pimps, hoping for rich men. More than anything, however, it attracted a generation of bohemian artists who had set up their ateliers in Montmartre: Renoir, Casas, Picasso, van Gogh and Toulouse-Lautrec, among others, all painted the Moulin.

Vincent van Gogh, Le Moulin de la Galette, 1886

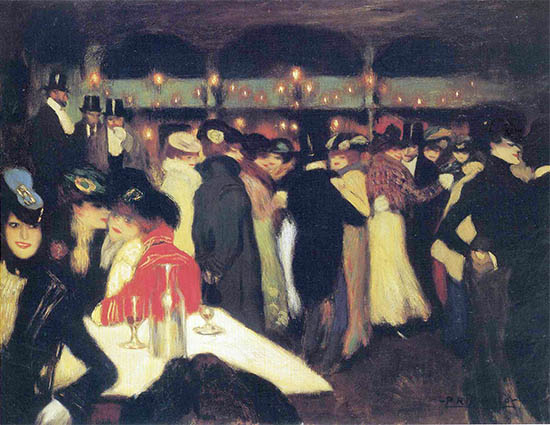

Pablo Picasso, Le Moulin de la Galette, 1900

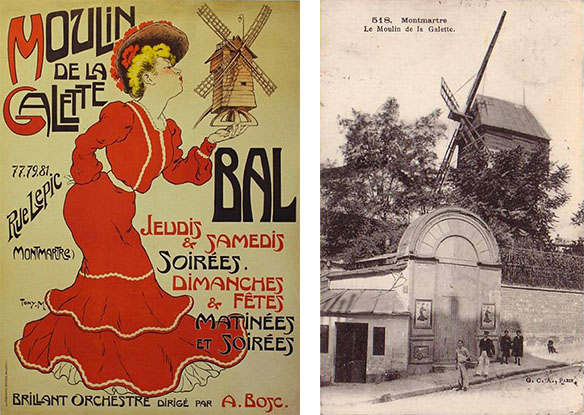

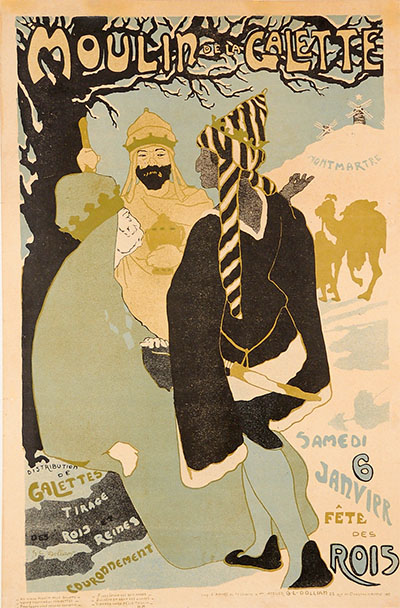

The Moulin also figured predominately in commercial art. It's turn-of-the-century advertising bills would be some of the earliest examples of the Art Nouveau poster:

Auguste Roedel, Moulin de la Galette, 1895

Anonymous, Moulin de la Galette, ca.1895 and in situ

Anonymous, Twelfth Night, ca.1900

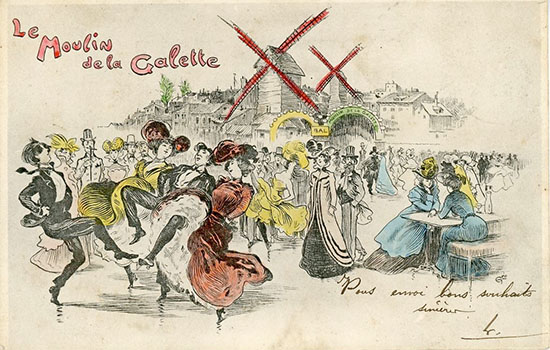

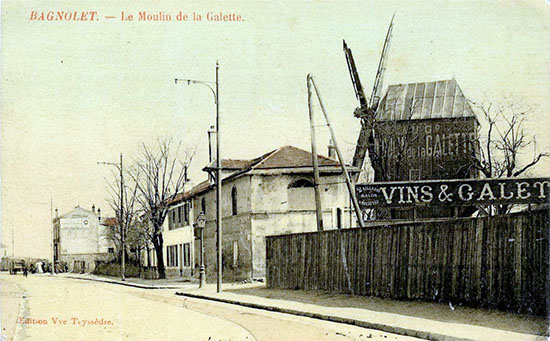

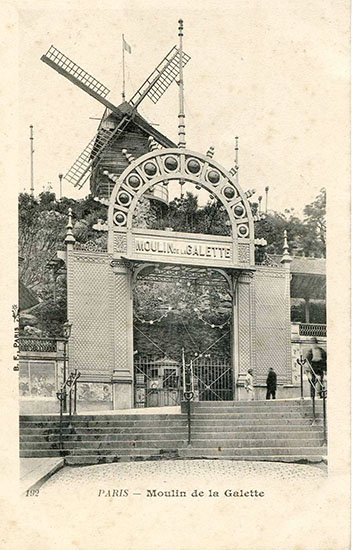

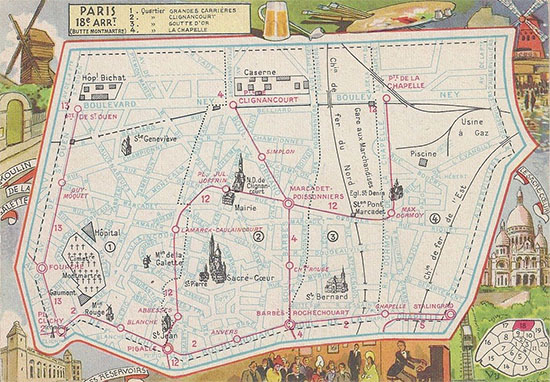

Of the 15 or so windmills that once dotted the butte, the Radet and Blute-fin were the last ones remaining. They became not only a symbol of Montmartre, but of fin-de-sicle Paris. They were frequently photographed and became, not suprisingly, a popular subject of the souvenir post card:

Eugène Atget, Montmartre Moulin de la Galette, 1899

Postcard, 1903

Postcard, 1946

In 1915 Pierre-Auguste Debray wanted to raze the Radet to make room for a new, larger cabaret. Facing popular outrage he donated the Moulin to the Vieux Montmartre society, who moved it to its current location on rue Girardon. During the last century the property was used, at various times, as an open-air dance hall, a cabaret and even a television studio, Today it is a cafe and private residence.

Dave Hughes, Moulin de la Galette, 5 Oct 2014

1. Renoir’s favorite model at the time was a 16-yo Montmartre seamstress named Jeanne (NLN). As he wrote “The girl was attractive, [with] wonderful hands, her fingertips somewhat swollen from needle pricks.” He, however, was unable to convince her to pose for the painting as she was apparently too busy conducting an affair with a local boy. Instead he used her younger sister Estelle as the central figure (in the blue and pink dress). For an analysis see: Hagen, Rose-Marie “Dancing on a Sunday in Montmarte” in What Great Paintings Say, Vol 2. New York: Taschen, 2003 (online).

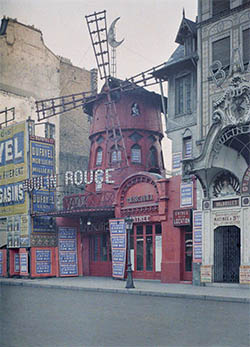

2. Another legend: Pierre-Charles’ wife collected her husbands remains and had them buried in the Cimetière de Montmartre. She placed a red-painted windmill on the headstone to represent the blood spilled over his moulin. When Charles Zidler and Joseph Oller opened their cabaret at the foot of Montmartre in 1889 they named it the Moulin Rouge after Debray’s headstone. Here is a 1914 autochrome by Albert Khan:

2 Nov 2014 ‧ Unclassified