Trial by Fire, Trial by Rain

The 1973 Indy 500

1732h, Tuesday, May 30th, 1973. The clouds came in “low and black” and soon the downpour began. On the 133rd lap of the Indianapolis 500 starter Pat Vidan waved the red flag and ordered in the few cars that still remained on the track. Even if the storm had passed it was obvious that there wouldn’t be enough daylight left to complete the race, but by this time that didn't matter: it had been a long, difficult month and no one wanted to be on that track for even a minute longer. Rain had delayed the race for three days and now, after only 332 miles, it was mercifully ending it.

Gordon Johncock, in his #20 STP Double Oil Filter Eagle, was declared the winner, but he seemed more relieved then happy. His teammate was in the intensive care unit and a crewmate was dead. Another driver was killed two weeks earlier and yet another was soon to be sent to a burn center. More than a dozen spectators had been injured and two were in the hospital with critical burns.

There had been tragic years at Indy before, but there had never been anything like 1973.

I—The 45 Second Lap.

0900h, Saturday, April 28th, 1973. Chief stewart Harlan Fengler officially opened the Indianapolis Motor Speedway for the 57th running of the 500 Mile International Sweepstakes (with awards over one million dollars). Veteran driver Gary Bettenhausen barely edged out several others and had the honor of being the first driver on the track. Fengler set a speed limit of 180 mph and within hours had issued his first speeding ticket. The next day he gave out another. It was clear that the drivers were champing at the bit to run faster than 180. In fact, a lot faster.

In 1912, the second year of the Indy 500 and first year that qualifications were recorded, David Bruce-Brown in his National runabout set a track record of 88.45 mph. It took nearly 60 years of incremental refinements to the chassis, the engines and the track itself for Peter Revson in his McLaren M16 to double Bruce-Brown’s speed, qualifying at 178.696 mph in 1971. The next year both turbochargers and bolt-on rear wings (an idea taken from sprint cars) were adopted and the results were anything but incremental: Bobby Unser qualified at 195.940 mph, beating Revson’s previous year record by a stunning 17 mph.

No one was fully prepared for this sudden increase in speeds. Even with the downforce of the new rear wings drivers had a hard time keeping their 1000- horsepower cars under control. “I jumped on the throttle coming out of [turn] two and spun my wheels halfway down the back straight–in high gear,” said driver Steve Krisoloff. Safety concerns had race teams and track officials on edge that May, but very few fans were paying attention. In 1973 everyone was anticipating a driver breaking the 200 mph barrier—the elusive 45 second lap.

1130h, Monday, April 30th. Fengler lifted the speed limit and practice began in earnest, however if theres one god-given certainty in this world, it’s that it rains in Indiana in May. Nevertheless, despite high winds and rain that washed out several days of practice, drivers began posting increasing speeds. On May 5th, a rare day with perfect weather, four drivers had laps over 195 mph and Swede Savage set a practice record of 197.802 mph. They were rapidly closing in on 200 mph and it seemed as if it was going to be an historic month at the Speedway.

II—Art Pollard.

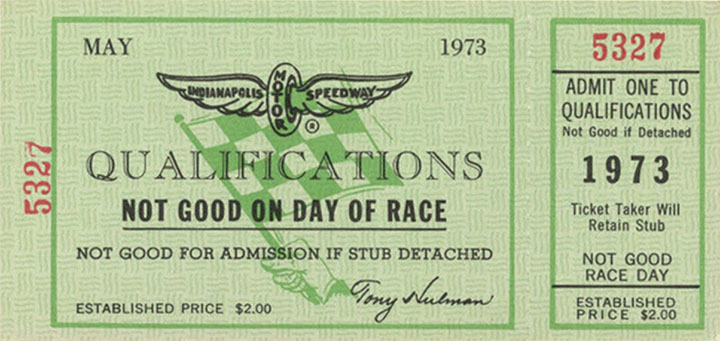

0500h, Saturday, May 12th. It was still dark out when my dad woke me and my older brother up to go to the first day of time trials. My dad had always been a fan of the Indy 500 and once we were old enough he began taking my brother and I to the time trials. 1973 was the first year he took me. I was a week away from being nine years old. Travelling up I-65 that morning in our turquoise Chevy Impala with a packed styrofoam cooler, a pair of binoculars and a fancy Swiss stopwatch my dad had commandeered from work (“Press here to start and stop. Press here to reset and whatever you do, don’t drop it”), I was, to say the least, excited for the day.

~0800h, Saturday, May 12th. We arrived at the Speedway, bought our two-dollar tickets and found seats in grandstand A. It was just us and a quarter of a million others that day. My first impression was how overwhelming the scale of the Speedway was. The track is technically considered an oval, but a better description would be a rounded rectangle: two 5/8-mile straightaways, two 1/8-mile “short chutes” and four left-hand 1/4-mile turns banked at nine degrees (a third of what most NASCAR tracks are banked). It’s so big that its impossible to see the whole track, or even most of it, from any given vantage point. From our seats we could see the main straightaway, the first turn and some of the first short chute.

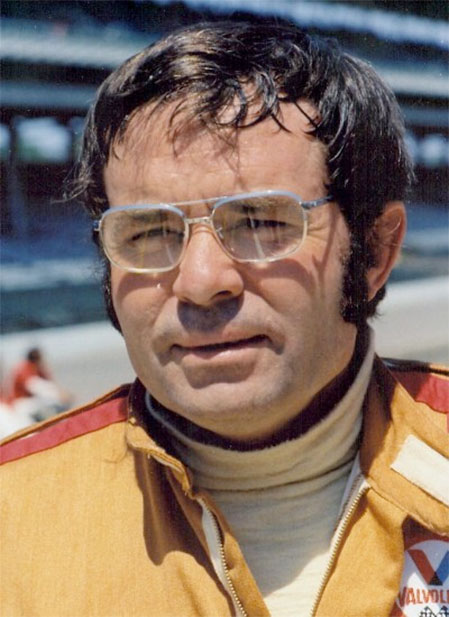

0937h, Saturday, May 12th. At 46 Art Pollard was the oldest driver at the track that May. He was the kind of guy who made time for everyone, whether you were a sponsor, a kid in the garages or one of his poker buddies. He was a fan of the Carpenters and a surprisingly competitive basketball player. Pollard came up through the sprint car ranks and had driven in six Indy 500’s. It seemed that 1973 was going to be his best year yet. “When things start out smooth and organized like this organization you know you’re going to do well,” he said of his Fletcher/Cobre team. He was running in practice above 190 mph and was assured a spot in the race. Robin Miller, an Indianapolis Star reporter, talked to with Pollard that morning and seemed surprised that he was going to take his car out for practice. “You’re good,” he said. “I think we can trim it out and get a little more out of it,” Pollard replied.

I was watching through my dad’s binoculars when Pollard’s car swerved into the outside wall in turn one. The only thing I remember was a trail of smoke leading through the short chute into the distance.

“Art had been driving the groove at the same spot earlier and seemed to almost lose it, then catch it at the last second,” said one witness, “This time it looked like he was going to go smoothly through the turn when the car suddenly turned right and went into the wall.” The car did a half-spin, hit the wall, went airborne through the grass then began flipping side-over-side, finally coming to rest some 1400 feet later in the middle of turn two. Pollard lie motionless, his head tilted foreward and his limp arm dangling over the side of the chassis. He was rushed to Methodist Hospital in the Speedway’s new cardiac ambulance but he never regained consciousness. He was pronounced dead an hour later. He was the 35th driver to die at the track.

1100h, Saturday, May 12th. Despite Pollard’s wreck the Speedway, exactly on schedule, began qualifications. That afternoon Johnny Rutherford, a close friend of Pollard’s, went out for his run. “It was my job,” he said, “That’s all you can say.” I had the fancy stopwatch and timed his third lap at 45 seconds. “Dad, he just did a 200 mph lap!” but he actually ran 199.071, some 40 feet short of 200 mph. I thought my nine year-old timing skills were on point, especially considering where we were sitting, but my older brother disagreed and immediately demanded the stopwatch. “Dad, tell him to give it to me, he doesn’t know what he's doing.“

Rutherford won the pole with a record speed of 198.413—not 200 mph, but close. In all 24 cars qualified that day. The next day, then the next weekend, which included rain, lightening, hail and tornado warnings, the field of 33 cars was completed. It was the fastest field in history.

III—Salt Walther.

0500h, Monday, Memorial Day, May 28th. The aerial bombs went off and the track opened for race day. Vehicles that had been queuing all night rushed into the infield to began the party. “Rain Threatens ‘500’ Race,” read that day’s Indianapolis Star and, indeed, it rained on and off all morning. Nevertheless, the traditional ceremonies went on—it wasn’t called “the Greatest Spectacle in Racing” for nothing. Around 1030h the Parade of Bands marched down the front straightaway. Later 89 year-old René Thomas, winner of the 1914 race, was driven around the track in his restored French Delage waving his checkered beret. The rain finally stopped, the track dried, and at 1500h Jim Nabors (an Alabama native, but whatever) performed the traditional “Back Home Again in Indiana” as thousands of helium balloons were released. Track owner Tony Hulman than uttered his famous line “gentleman, start your engines.”

We weren’t at the track that day. We were home, grilling out and listening to Sid Collins call the start of the race on the radio. On the very first lap he said “There's been a tremendous crash here. The red flag is out. The red flag is out. We’ll not try to guess how many cars but in the back of the pack something happened.” It was obvious that the wreck was bad but it wasn’t until that evening, when ABC broadcast the race, that we could see just how bad it really was.

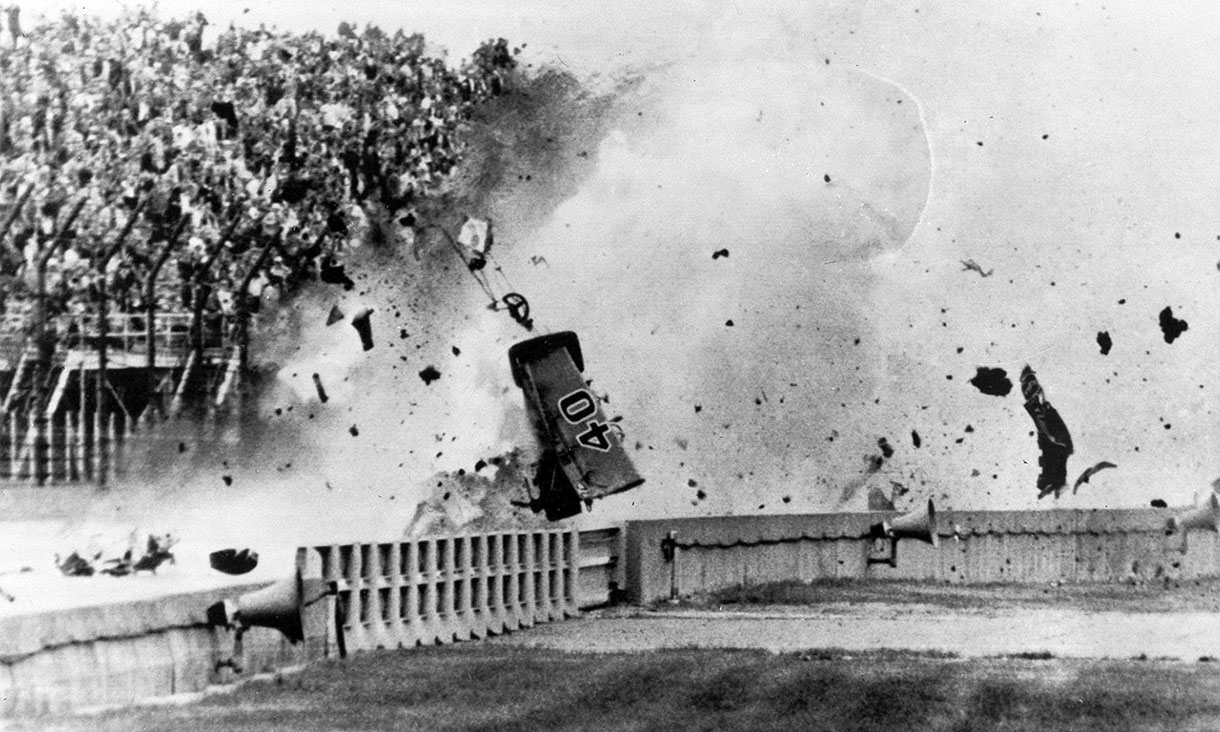

“It was a very, very untidy field,” Jackie Stewart said on TV. Driver Mike Hiss, starting in ninth row, recalled coming around turn four and “As far ahead as I could see there were no rows, just cars in random order... then suddenly all hell broke loose.” Jerry Grant, on the outside of the sixth row said “I saw Salt [Walther] veering to the right and coming at me... he hit my front wheel so hard it almost jarred the steering wheel out of my hands.” Walther’s #77 Dayton Steel Wheel McLaren flipped over Grant’s car and went airborne into the catch fence, shearing off the nose of the car, shredding the chain links, snapping the stand poles and sending a shower of methanol into the crowd. The car then spun upside down like a pinwheeling roman candle down the straightaway. Behind him were the littered remains of 11 other cars that couldn’t avoid the melee. “This is what everyone has feared,” said Jim McKay, “There’s been a terrible atmosphere here all weekend long.”

Note that Walther’s legs are completely exposed

At 24 dark-haired, athletic David “Salt” Walther was the youngest driver at Indy that year. He was the son of the Dayton, Ohio steel tycoon George Walther, who had been fielding cars at Indy since 1958. Walther began piloting hydroplanes in his teens and first drove at Indy in 1972. “I’m thrilled to death driving both machines,” he told a reporter. To many, however, he was a dilettante, riding on his fathers coattails. His cocky, wealthy playboy persona charmed the girls but it didn’t exactly endear him to the other drivers.

While emergency crews were extricating Walther from his car, others rushed stretchers into the stands. “The next thing I know was that I was hit in the face with fuel. I was just drenched and I dove to the ground,” said Scott Johnson. After the shower of methanol came the intense heat. “I thought I was going to die. I thought it was all over,” said Lori Stanley. In all 13 spectators were injured, including two Indiana teenagers who were critically burned.

Walther was airlifted to the hospital and crews began clearing the track and repairing the fence, but before the race could be restarted it began to rain. Officials decided to start the race from scratch the next morning.

~0800h, Tuesday, May 30th. By the second day everyone was tired and tempers were short. The morning meeting between the drivers and race officials was, to say the least, contentious. One driver said “if you don’t shape up the start of this race you’re going to get us all killed out there.” It was finally decided to increase the pace speed from 80 to 100 mph. The weather had delayed the restart until 1100h and after a single parade lap the field was red flagged—it began to rain again. Crews covered the cars with tarps and tried to wait it out but the rain never stopped. The race was rescheduled for the next day.

“Ladies and gentleman, obviously we have a very serious situation here,” said Tom Carnegie, the Speedway’s public address announcer. The race had never been cancelled two days in a row before and the conditions at the track were becoming dire: the concessions were out of food, the bathrooms were overflowing with trash and the infield had become a soggy mess. It was so bad the the health department threatened to shut down the track if the race wasn’t run the next day. Not everyone seemed to mind, however; one spectator in the infield told the Indianapolis Star “Hey, you Mr. reporter, just let ’em know this ain’t no race, it’s a drug party.”

IV—Swede Savage.

If Salt Walther was the rich playboy, then the 26-year old blond-haired Californian David “Swede” Savage was the matinee idol. He began racing motorcycles as a teenager and eventually became part of Evel Knievel’s Stunt Show of Stars where he was noticed by Ford, who signed him to race for their NASCAR team. After only a half season the legendary Dan Gurney signed him to race for his Can-Am and Trans-Am teams. In 1970 he moved up to Indy Car racing. Car & Driver declared him one of the ten best drivers in the world, but others felt that he was in way over his head. Bobby Unser said “If you looked the world over, you wouldn’t even have to put him in the top hundred, and there aren’t that many good race drivers around.”

In 1971, at a race in Ontario, California, his throttle stuck open, his car hit the wall and he suffered severe head injuries. He was briefly in a coma and suffered amnesia. Gurney suggested he take a sabbatical but five months later he was racing again. When he returned some felt that his head injuries had impaired his driving judgement, even to the point of being a danger on the track.

In 1972, his rookie year at Indy, Savage finished in 32nd place, second to last only to another rookie—Salt Walther. The next year he signed on with Pat Patrick’s STP-sponsored team and began to prove his detractors wrong. That May he set the practice record and even briefly held the pole. He started the race on the inside of row two and had established himself as one of the drivers to beat.

0700h, Wednesday, May 30th. By this time many of the Speedway’s seasonal workers—everyone from the janitors and concessionaires to the doctors and nurses in the infield clinic—had returned to their regular day jobs. There were so few ticket-takers left that they didn’t even bother asking for rain checks. 350,000 race fans came on Monday but less than a third of that had shown up on Wednesday. The papers began calling it the “72 Hours of Indy.” “They could have just as well red-flagged the thing and we would have been happy to have gone on to Milwaukee,” said Johnny Rutherford.

1410h, Wednesday, May 30th. After yet another weather delay the race finally began. This time the start was clean and veteran driver Bobby Unser took the early lead and dominated the race until an unfortunately long pit stop relegated him to third place. Gordon Johncock assumed the lead for a few laps then the race became a duel between Savage and Bobby’s brother Al Unser.

When the race started I was at school. I remember it being track and field day—one of those days at the end of the year where teachers didn’t want to teach and students didn’t want to learn. I was just finishing the day when the race started. I heard what happened on the radio, but again, I had to wait until that evening to see it.

As the race progressed the track became dirty with rubber, oil and the debris of cars travelling 180 mph. As Jerry Grant said “The track is extremely oily and everyone I’ve been around is slipping and sliding and having a very difficult time. We’re shooting a completely different line through the turns. Instead of going through the groove, we’re going down across the apron trying to stay out of the oil then coming back across the oil, [but] you have to cross that groove sooner or later.” When asked if the track was unsafe he said “well, it’s making an old man out of me.”

1512h, Wednesday, May 30th. On lap 59 Al Unser committed to a pit stop and Savage, who had fueled and received a new tire two laps earlier, was poised to take the lead for a second time. It may have been the slippery groove, or the cold tire, or a problem with his rear wing, but coming out of turn four he suddenly veered left and hit the angled inside wall head on. His car, the day-glo red #40 STP Oil Treatment Eagle, instantly disintegrated into a massive fireball, sending his engine and transmission tumbling down the main straightaway and his tires some 40 feet into the air. “I can’t even tell what part of the car he is in,” said Jim McKay.

Savage ended up near the outside wall in a fragment of the cockpit. The image of him sitting upright in a methanol fire, still in his seat and completely exposed, was disturbingly reminiscent of the famous Burning Monk photo. “How he can be moving is beyond me. I’ve never seen a car just disintregate like that,” said Chris Economaki. But Savage wasn’t just moving, he was talking, even joking with the rescue crew. Like every driver he was wearing the standard impact-resistant helmet and fire-resistant balaclava, gloves and shoes, but he was one of only a few that were wearing the new Nomex foam-filling suit. It seems certain that the suit saved his life—at least for the time being.

Emergency crews rushed to the wreck. “All of a sudden things cleared up on the pit road and I had a clear shot all the way up to Savage’s car which I could see burning,” said fireman Jerry Flake, “Then out of nowhere, a guy was in front of me...” Armando Teran, a 23 year-old truck driver from California, came to Indy to work as sign board operator for Graham McRae’s pit team. He ran towards the wreck directly into the path of Flake’s truck, which was driving in the opposite direction of normal traffic. There was an audible gasp from the crowd when Flake struck Teran at 60 mph. Teran was pronounced dead when he arrived at the hospital. “I wake up in the middle of the night and see this fellow lying out in front of the truck. It still bothers me—it’s something you can’t forget,” Flake later said.

1626h, Wednesday, May 30th. After Savage’s wreck was cleaned up the field restarted and it soon became a race of attrition. On lap 73 Al Unser blew his engine and Gordon Johncock took the lead which he never relinquished. By the time the rain began on lap 129 there were just 12 cars still running and only two on the lead lap. At 1738h, five minutes after Vidan waved the red flag, Johncock was summarily declared the winner. There was no checkered flag. In the hastily prepared winner’s circle Johncock, who had just filed for bankruptcy and was now getting the biggest payday of his life, said “It’s the greatest thing that ever happened to me,” but his damp celebration was clearly troubled. “It’s not a great day for me,” said the normally garrulous STP sponser Andy Granitelli. “Very sad, about as sad as you can get. I still feel bad about it,” car owner Pat Patrick said 40 years later. Johncock’s traditional winner’s banquet that night, typically the capstone of the month, was take out from a local Burger Chef.

Is the person behind Johncock Jack Nicholson? I don’t think so, but then again...

By the next morning everyone had packed up and moved on to the next race, glad to finally leave that month at Indy behind.

V—Epilogue.

After a stay at Methodist Hospital Salt Walther was flown to the University of Michigan Burn Center. He was burned over 40% of his body. He lost the fingers on his left hand (which he covered with a glove for the rest of his life) and underwent numerous skin grafts on his right leg.

“I never took a drug in my life, ever, until I had the wreck,” he said. But after months of morphine in the hospital, Walther developed an affinity for prescription pain killers and later cocaine and heroin. Remarkably he attempted a comeback (and even finished ninth in the 1976 race), but could never shake his addiction.

His later troubles included everything from stealing a golf cart, passing bad checks, side-swiping a line of exotic cars outside of a California party,

illegally obtaining prescription drugs, child endangerment, failure to pay child support and evading police on a high-speed chase. He spent time in and out of Ohio prisons before dying of undetermined causes at the age of 65 in 2012.

Swede Savage arrived at the hospital with two broken legs, a broken arm, burns and internal injuries. Although critically injured he was expected to recover. He couldn’t speak because of his lung injuries but could write in a notebook. “Be careful,” he wrote to his best friend, the motorcycle racer Eddie Wirth (advice that neither had ever heeded). Several days after his note to Wirth—33 days after the accident—he died. The official cause of death was pneumonia but his attending physician, Dr. Steve Olvey, later said it was due to hepatitis B from a tainted blood transfusion. He was survived by his daughter and pregnant wife. He was the 36th driver to die at Indy and remains one of the greatest “what if...” stories in the history of the sport.

After 1973 my dad took me to several more time trials. I vaguely remember the streakers during the rain delay in 1974, but other than that the specifics are lost to the mists of time. I’m no longer really a race fan and aside from perhaps Danica Patrick (via her GoDaddy commercials) I'd be hard-pressed to name a single driver in the last decade. But every Memorial Day weekend I still pay attention, if only fleetingly, to the race. Of course I’m not thinking about the current drivers or their cars, I’m thinking of those Saturdays in May I spent with my dad 40 years ago.

—May 22nd, 2017. Unclassified