74

Tabulae Anatomicae

Julius Casserius

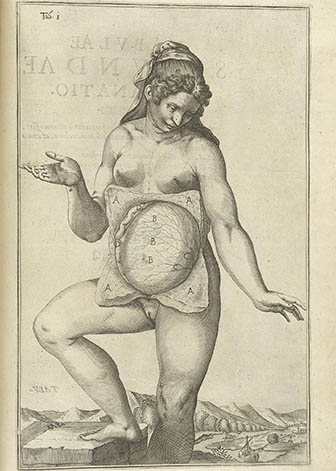

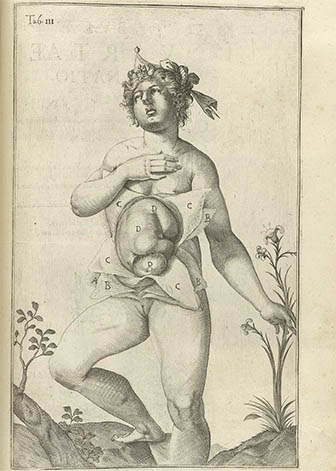

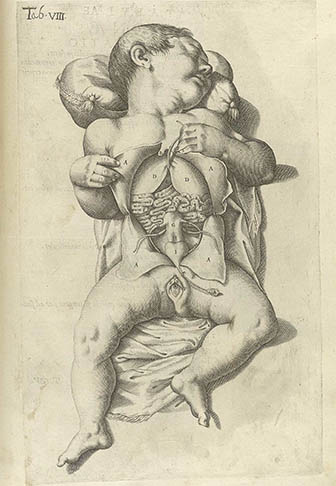

Here is a copperplate engraving from De formato foetu liber singularis, commissioned by the Paduan anatomist Casserius. It shows a classic renaissance Venus filleted lotus-like to reveal her child.1 The plate, as well as some 95 others, represent the high point of Paudan/Venetian anatomical illustration and were published in three separate titles after Casserius’ untimely death.

Julius Casserius (AKA Giulio Caeesrio, Giulius Casseri, or Casserii Placentini) was born ca.1556 or ca.1561 in Piancenza, Italy.2 Casserius’ father died when he was young and, being nearly destitute, he entered the houshold of the noted Paduan Anatomist, Girolamo Fabrizi d’Acquapendente (AKA Fabricus). After showing extraordinary initiative, the master took it on himself to teach Casserius anatomy. Casserius went from family servant to auditor to surgical disciple.

Casserius enrolled in the Università Artista and studied under both Fabricus and Gerolamo Mercuriale (Mercurialis). After his graduation, ca.1580, he acted as Fabricus’ preprator, university surgical examiner, as well as a physician and surgeon.

But there would soon be trouble in Padua. In 1595 Casserius became a substitute for Fabricus and his lectures were a bit too enthusiastically received for Fabricus’ taste. The old master, enraged with jealousy, banned Casserius from giving private lectures through an old statutory rule. According to the records it would be nearly eight years until Casserius lectured again.

During this time Casserius began to publish his first works on anatomy: De vocis auditusque organis Historia anatomica3 was published in 1601 and Pentaestheion4 in 1609. After these books he began writing the text and compiling the drawings for a comprehensive atlas of anatomy.

Back to the rivalry: In 1613, after 50 years of public lectureship, Fabricus was permitted to scale back his teaching, and his replacement, against his wishes was, of course, Casserius. In 1616 Casserius began his first and only public anatomy lecture. Shortly after the three week course he caught a fever and died on 8 Mar 1613. His master and nemesis, Fabricus, would survive him by three years.

After Casserius’ death his commissioned plates, via his heirs, ended up with Adriaan van der Spieghel (Spigelius), who had succeeded both Casserius and Fabricus as professor of Anatomy and Surgery. Spigelius intended to use the plates in his own anatomy atlas, but died an untimely death in 1625.

Here is where all the bibliographic fun begins. After Spigelius’ death, his son in law, Liberale Crema, edited one of his manuscripts and illustrated it with nine of Casserius’ plates. The book, De formato foetu liber singularis, published in 1626, was perhaps the first OB-Gyn classic.5 A year later, Jan Rindfleisch (AKA Bucretius) edited Spigelus’ unfinished altas and illustrated it with Casserius’ plates.6 In 1627 he also published 95 of the plates with his own annotations, as Tabulae Anatomicae.7 Some time later the Tabulae and De formato foetu were published as a single volume.

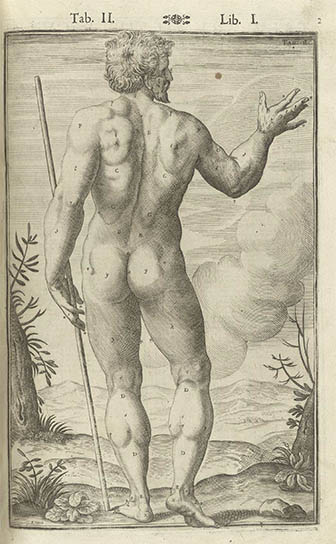

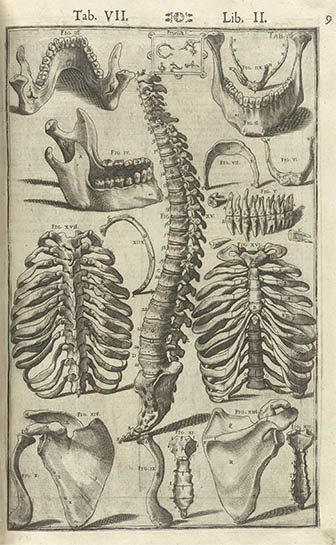

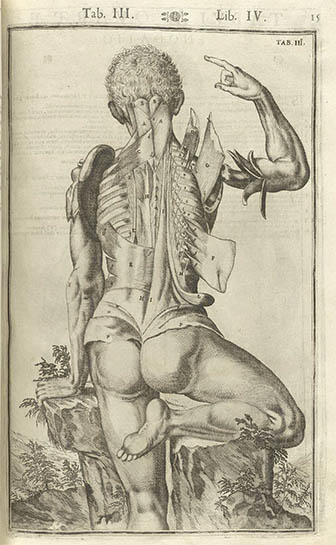

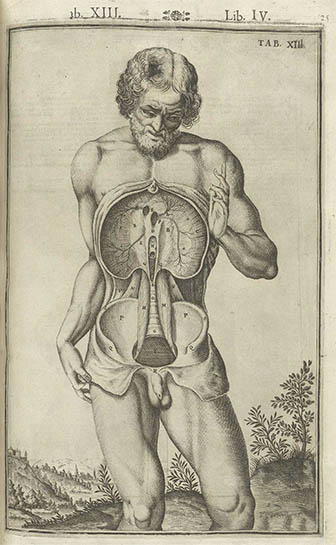

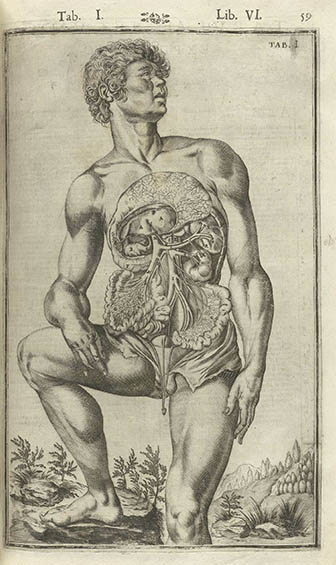

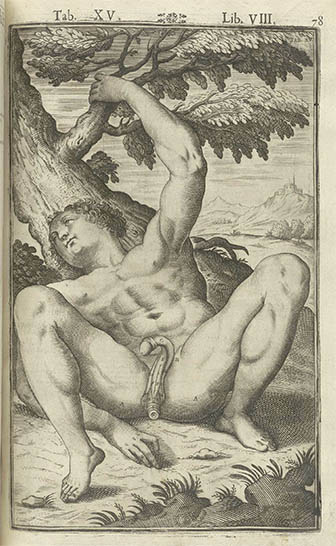

Here are some plates that appeared in both Spigelius’ Fabrica and Casserius’Tabulae:

Since Vesalius’ de Fabrica, the Paduan anatomists relied on the artists of Venice and Casserius was no exception. His plates were drawn by the Venetian painter and print-maker Odoardo Fialetti (AKA Edoardus Fialettus), who studied under Tinoretto, and the engravings were prepared by Francesco Valesio (Franciscus Vallesius).

If Vesalius’ illustrations were the model for the woodblock then Casserius’ illustrations were the model for copperplate. It would be nearly 80 years before better anatomical illustrations were published and Casserius’ work would be plagiarized well into the 18th century.

Here are few more plates from De formato foetu:

1. Or, more specifically, a late third trimester gravid female with skin, uterus and chorion reflected to show the fetus and placenta. This, as well as the rest of the images presented here are from the NLH’s Historical Anatomies on the Web, which your humble narrator told you previously he would crib heavily from.

2. For a complete review of Casserius’ place in anatomical illustration see: Riva, Alessandro, et. al. Iulius Casserius (1552–1616): The Self-Made Anatomist of Padua’s Golden Age. The Anatomical Record (New Anat.) 2001 265(4):168–175, which is available as an online pdf.

3. Placentini, Casserii. De vocis auditusque organis Historia anatomica. Venice: Ferrariae, 1600–1601. The folio consisted of two treatises: De Aure auditionis organo, printed in 1600 and De Larynge vocis organo, printed in 1601. The plates are available at BNF’s awesome Gallica database.

4. Placentini, Casserii. Pentaestheion, hoc est, De quinque sensibus liber, Organorum Fabricam... Venice: Nicolaum Misserinum, 1609. The entire text is available online from Biblioteca National De Portugal.

5. Speigel, Adriaan van de, Casseri, Giulio Cesare. De formato foetu liber singularis. Padua: Io. Bap. de Martinis & Livius Pasquatus, 1626. The entire text is available online at Gallca.

6. Spiegel, Adriaan van de, Casseri, Giulio Cesare. De humani corporis fabrica libri decem. Venice: Evangelista Deuchino, 1627.

7. Casseri, Guilio Placentini. Tabulae Anatomica LXXIIX. Venice: Evangelista Deuchino, 1627.

3 Nov 2010 ‧ Anatomicae