73

The Autochrome

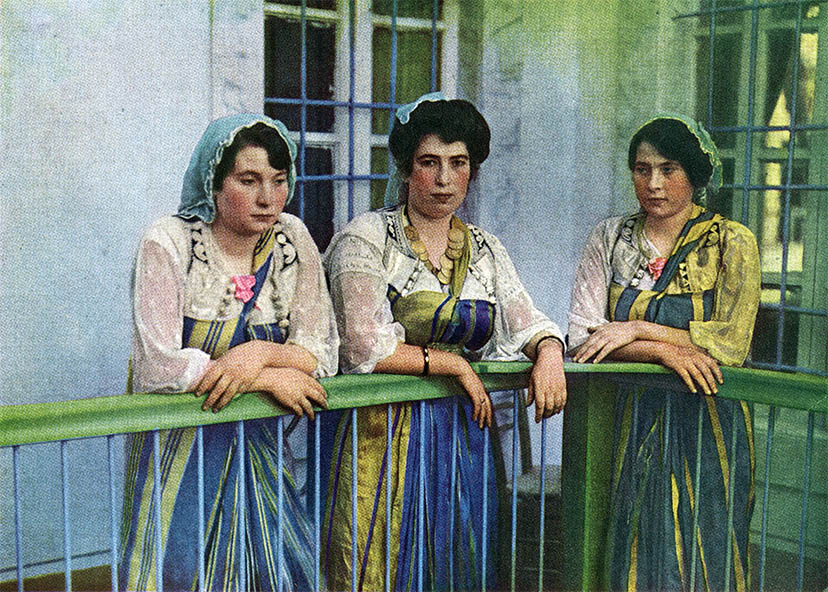

National Geographic and the Autochrome in America

This image, a scan of an engraving of a glass Autochrome plate, was published in the Aug 1925 issue of National Geographic.1 It ran with the caption of “Young Women of Tripoli in Holiday Dresses,” although it might as well have been captioned “Young Women of Tripoli Stare Dourly in Completely Different Directions.”2 The image was rather typical of the posed and costumed images of National Geographic during the 1920s. Here are a few more images from the article:

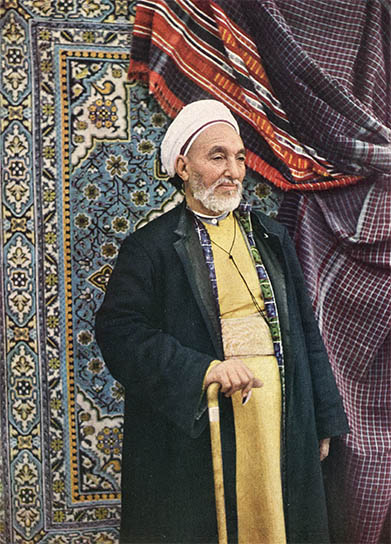

A Mohammedan Priest of Tripoli

A Town-bred Arab Women, Tripoli

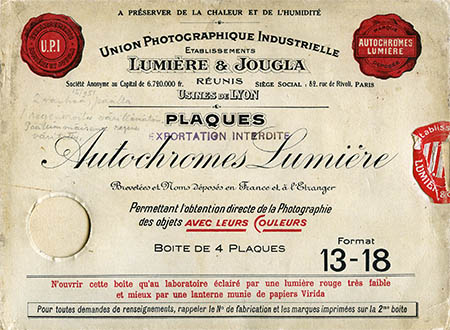

After inventing the cinématographe in 1895, which alone would secure their place in photographic history, the brothers Auguste and Louis Lumière of Lyon, France turned their attention toward color photography. By 1903 they had perfected and patented the first commercially viable color process – the Autochrome.3 Lumières’ invention was presented to L’Académie des sciences on 30 May 1904 and the first commercially-prepared plates were sold in 1907:

The Autochrome consisted of a glass plate with a screen of dyed pomme de terre starch granules and a B&W silver bromide emulsion. After the image was exposed an additive direct-positive color image was produced.4

The plates were slow (1 sec at f/8 in full sunlight), fragile, exceptionally grainy, subject to random color variations and required backlighting for proper viewing. But their appearance, often described as pointillistic, made it in the eyes of many, one of the most beautiful photographic processes ever. The Autochrome was widely adopted, especially by amateur photographers, and would be the dominant color process for the next 20 years.

It didn’t take long for periodicals to publish engravings of Autochrome plates. In 1907 they began appearing in the French periodical L’Illustration. In America, National Geographic began publishing Autochromes in 1914.

By the 1920s NG was routinely featuring Autochrome images and in 1927 it began publishing color images in every issue of the magazine. Between 1914–1938 the Society acquired a library of more than 12,000 Autochrome plates and published 2355 Autochrome images, perhaps more than all other American periodicals combined.

Here are several images from a series of 11 Jamaican scenes, photographed by Jack Guyer, which ran in the Jan 1927 issue:5

Ready for Dress Parade

Where Climatic Zones Meet

Where the Blue Begins

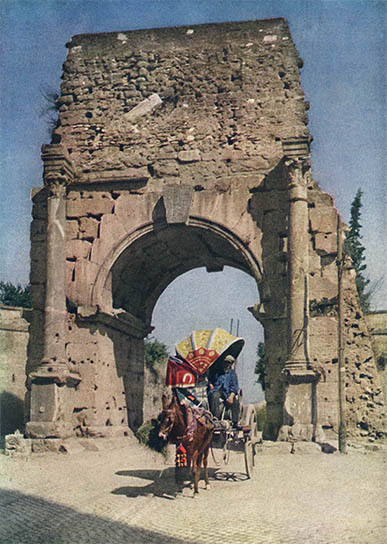

This series of 33 images of Italy by Hans Hildebrand ran in the Apr 1928 issue:6

The Arch of Drusus Spans the Appian Way

Rome’s Magnificent Monument to a Great King and Unknown Warrior

A Defect that has Brought Enduring Fame

She Bids You Hail and Farewell to Italy

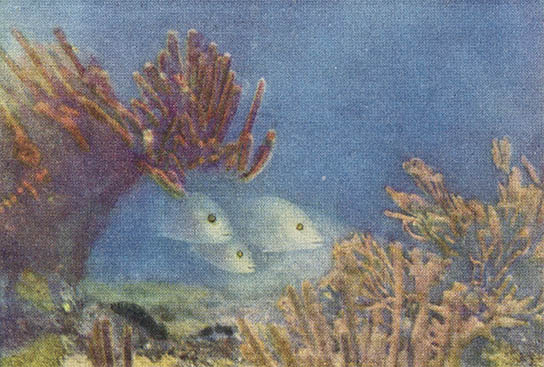

Most of NG’s Autochromes published during the 1920s were typical travelogue images – monuments, scenery, locals posed in costume or the occasional bare-breasted Balinese maiden – but the magazine also published several technically groundbreaking series. These blurry images, photographed by the noted ichthyologist William Longley and Charles Martin of NG’s photo lab, were the first ever underwater color photographs:7

Hogfish in Banded Phase, Resting among the Gorgonians

Gray Snappers among the Gorgonians

The Yellow and Black Porkfish, One of the most Gaudy of Reef Fishes

NG begin to phase out Autochromes in favor of newer and faster processes, such as the Finlay (1930), Agaiacolor, Dufaycolor (1937) and finally the Kodachrome (Apr 1938).

1. Pellerano, Luigi. “Under Italian Libya’s Burning Sun.” The National Geographic Magazine. 1925 Aug;48(2).

2. Is it just me, or is the girl to the right totally eyeing the girl on the left? Hmm...

3. A. Lumière et ses fils. “Procede de Photographie en couleur.” FR patent 339,223. 17 Dec 1903. Which is, sadly, outside of Esp@cenets date range. See also: August Lumière and Louis Lumière. “Photographic Plate for Color photography.” US patent 822.532. 5 Jun 1906.

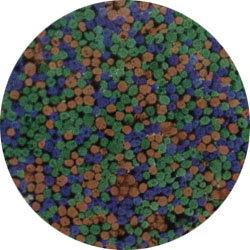

4. The manufacturing process consisted of coating 20 × 84 cm glass plates, 0.9–1.8mm thick, with a tacky latex-based varnish, then dusting the plate with a mixture of aniline-dyed potato starch granules colored violet (ethyl violet, 27%), orange (erythrosine, 32%) and green (orthochrome T, 41%) and finally dusting with carbon black to fill in any open spaces. The plates were then laminated by a roller press, sealed with varnish and finally coated with a B&W silver bromide emulsion. The finished plates were then cut into standard sizes. Here is the obligatory photomicrograph of the dyed-starch granule screen:

The plates were exposed, typically through a yellow filter, emulsion side last, and developed using mostly standard dry-plate techniques and chemicals. For a wonderfully comprehensive review see: Autochromes Lumière - La Photographie des Couleurs, or, Wood, John. The Art of the Autochrome: The Birth of Color Photography. Iowa City: University of Iowa Press, 1993.

5. Gayer, James. “The Color Palette of the Caribbean.” The National Geographic Magazine. 1927 Jan: 51(1).

6. Hildebrand, Hans. “Man and Nature Paint Italian Scenes in Prodigal Colors.” The National Geographic Magazine. 1928 Apr: 53(4).

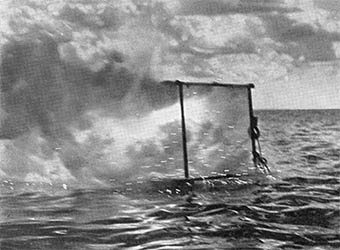

7. Longley, W. H., Martin, Charles. “The First Autochromes from the Ocean Bottom.” The National Geographic Magazine. 1927 Jan: 51(1). To take these images off the Dry Tortunga Islands (70 mi west of Key West) the noted ichthyologst W. H. Longley and the director of NG’s photographic laboratory, Charles Martin, developed a new, faster Autochrome emulsion. This new emulsion, however, still required an additional light source and Martin’s solution was to detonate a pound of magnesium via a dry-cell as a flash (the equivalent of 2400 flashbulbs – something that you probably don’t want to try at home):

It should be noted that magnesium readily burns a brilliant white in oxygen, nitrogen and even in water. Martin’s flashes could completely illuminate the water to a depth of 15 ft. Although after a misfire Dr. Longley was seriously burned (and incapacitated for six days), the project was considered a technical success.

14 Oct 2010, updated 8 Oct 2011 ‧ Photography