109

The Streets of New York

Part II – 19th Century Exansion

Soon after the Commissioners Plan (see part I) was adopted construction of the street grid began. Despite considerable and vocal opposition it proceeded with remarkably few major changes or alterations.

The Plan was notoriously unaccommodating of existing properties. Farms and estates were divided, houses, suburban villas, even a hospital, were razed to make room for the new streets. It was estimated that two of every five structures were simply “mapped over.” 1

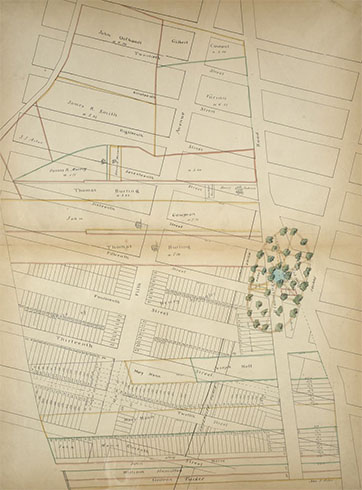

This map,2 a later version of Randel’s original Farm map shows the existing farm plots in 1815 overlaid by the proposed grid (as well as the later location of Union Square):

The Sackersdorff map, NYPL

The Commissioners were even less concerned with the island’s geography and ecology. Hills and bluffs were leveled, valleys filled in and streams and marshes buried. As Clarke famously said of the Commissioners: “These are men who would have cut down the seven hills of Rome.” 3

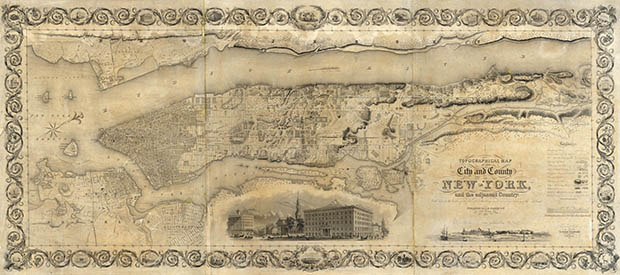

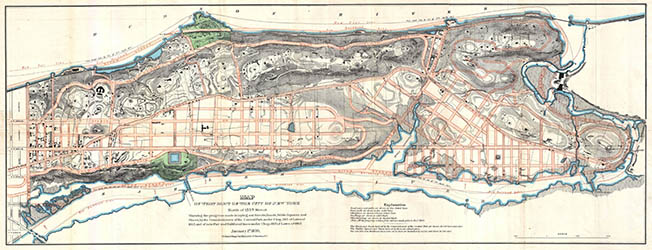

This beautiful steel-plate engraving by S. Stiles and Co was published by J. H. Colton in 1836. It shows an overlay of the current and proposed grid as well as the remaining topographic and geologic features of the island:

The Colton map, The Rumsey Collection

This map from 1865 by the civil engineer Egbert Ludovicus Viele shows not only the current grid but a pre-development view of Manhattan’s topography and hydrology. Viele, a civil engineer, spent nearly 20 years consulting historic maps and plans as well as conducting new surveys to compile what would turn out to be one of the most important maps of the city ever published.4

The Viele map, The Rumsey Collection

As the city’s population grew (it doubled every 20 years throughout the 19th century) the grid expanded north. First Avenue was opened in 1813, 21st street in Chelsea in 1834 and 57th street in Midtown in 1844.5

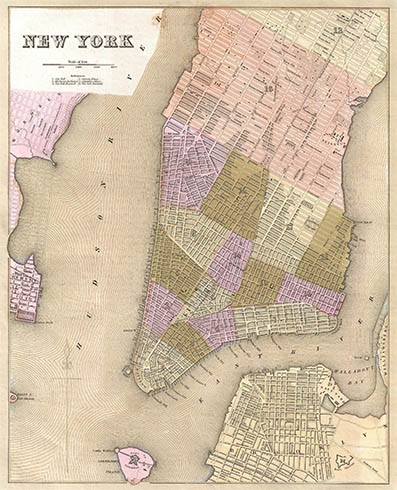

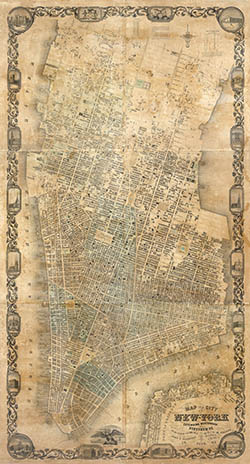

This map, engraved by George Boynton, was published by Thomas Bradford in his Illustrated Atlas.6 It shows the extent of the the grid ca.1839:

The Bradford map, Geographicus

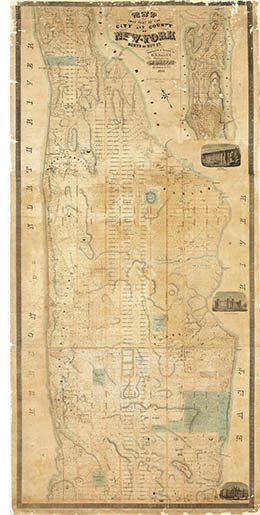

These maps, prepared by R.A. Jones (north map) and John F. Harrison (south), were published by Matthew Dripps in 1851 and 1852, respectively. In addition to the grid overlay, the Dripps maps were the first to show individual lots and buildings and were the precursors of the the Bromley and Sanborn insurance maps. Taken together they show an amazing detail of mid-19th century Manhattan.

The Dripps maps, The Rumsey Collection

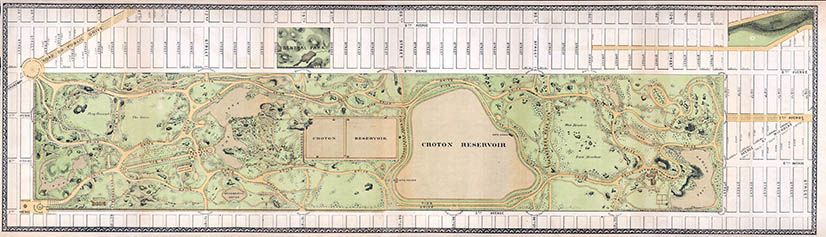

The original 1811 Plan had little provision for public parks. The commissioners argued that there were perfectly good rivers on each side of the island to serve this purpose. This oversight was rectified by the city in 1853 when they acquired 700+ acres of “a bleak, rubbish-strewn area littered with squatters’ shacks,“ and over the next 16 years constructed an English-style manicured public space – Central Park.7 Although the commissioners could not have anticipated this development their plan was able to accommodate it.

This 1 Jan 1870 map which appeared in the Thirteenth Annual Report of the Board of Commissioners of the Central Park8 was a poorly registered version of Vaux and Olmstead’s original 1863 map. It shows the nearly completed park in situ.

Vaux and Olmstead map, Geographicus

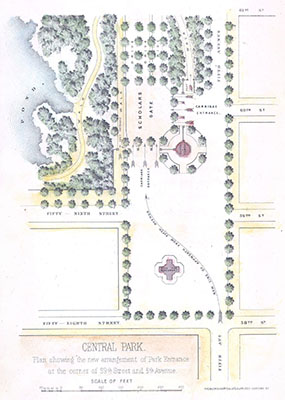

This vignette, also from the Thirteenth Annual Report, shows the proposed landscaping and traffic changes (think carriages here) at the Fifth Avenue and 58th Street entrance.

Scholars Gate entrance, Geographicus

By the 1860s significant parts of the street grid extended as far north as 155th street – the limit of Randals 1811 survey. It was clear that additional planning was needed and in 1865 Albany gave the Central Park Board of Commissioners the authority (under N.Y. Law c.565, 1865) to lay out the streets and roads on the northern part of the island.

This 1870 lithograph by Major & Knapp depicted their proposed street grid as well as new piers and bulkhead lines and was (again) included in the Thirteenth Annual Report.

The Knapp map, Geographicus

By the beginning of the 20th century the Manhattan street plan was, for all practical purposes, complete. In less than 90 years two generations of politicians, planners and developers had transformed some 12,000+ acres of wilderness into an urban grid. It was of of the most remarkable public works projects of the 19th century.

Having run out of space on the island, future developers simply built in the last dimension remaining – up – and that is a topic for part III.

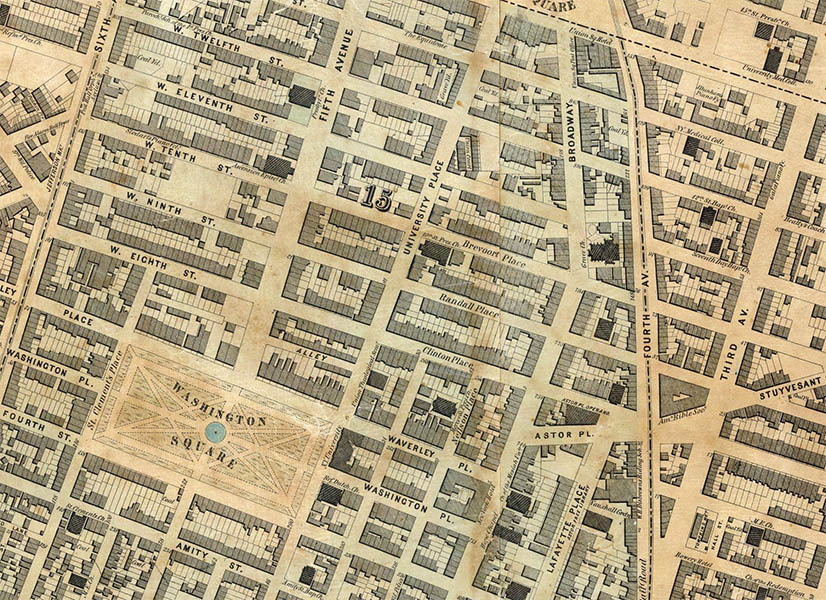

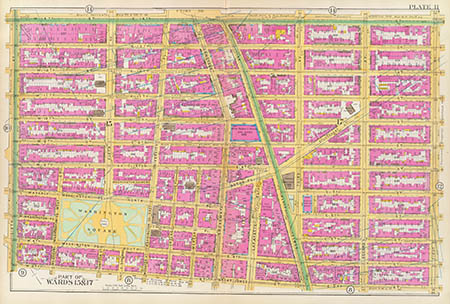

Greenwich Village, Bromley insurance map, 1891. The Rumsey Collection

1. Which led none other than Edgar Allen Poe to remark that “In fact, these magnificent places are doomed. The spirit of Improvement has withered them with its acrid breath. Streets are already “mapped” through them, and they are no longer suburban residences, but “town-lots.” In some thirty years every noble cliff will be a pier, and the whole island will be densely desecrated by buildings of brick...” “Doings in Gotham.” Columbia Spy. 1844 18 May: XV (4): 3.

2. Sackersdorff, Otto. Map of farms, commonly called the Blue book, 1815. Drawn from the original on file in the Street Commissioner's office in the city of New York, together with lines of streets and avenues, laid out by John Randel, Jr. 1819–1820. New York: City Surveyors. 1868.

3. Clarke, Clement Moore. A Plain Statement, Addressed to the Proprietors of Real Estate, in the City and County of New-York. New York: J. Eastburn and Co., 1818.

4. Today, some 140+ years later Viele’s map is still regularly used by architects, planners, structural engineers, et. al. to determine the stability of the ground. You pour a foundation in the city without consulting Viele at your own risk. For more see: Wiprud, Brian. “Uptown Headwaters: Confessions of a Manhole Detective.” Mercator’s World. May/Jun 1997 2–3: 42–45, or Kurutz, Steven. “When There Was Water, Water Everywhere.” New York Times. 11 Jun 2006 (online).

The map was published in several different versions between 1865–1874. For an original version see Kevin Brown’s Geographicus. The 1874 version from the Atlas of the city of New York is available from the Rumsey collection.

5. For an interactive map of historic street openings see: “How Manhattan’s Grid Grew.” New York Times. 20 Mar 2011.

6. Bradford, Thomas. An Illustrated Atlas, Geographical, Statistical, And Historical, Of The United States And The Adjacent Countries. New York: Wiley and Putnam. 1839. As you can see from the map this is plate 18.

7. A complete history of the park is well outside your humble narrator’s abilities. For more information see: Rosenzweig, Roy, Blackmar, Elizabeth. The Park and the People: A History of Central Park. Ithaca, N.Y.: Cornell University Press, 1992. For a few online histories see: the Parks official site, the Central Park Conservancy site or centralparkhistory.com.

8. Thirteenth Annual Report of the Board of Commissioners of the Central Park, for the Year Ending December 31, 1869. New York: Evening Post Steam Presses, 1870. The report is available as a pdf from nyc.gov.

1 Dec 2011 ‧ Cartography