108

The Streets of New York

Part I – The Commissioners’ Plan

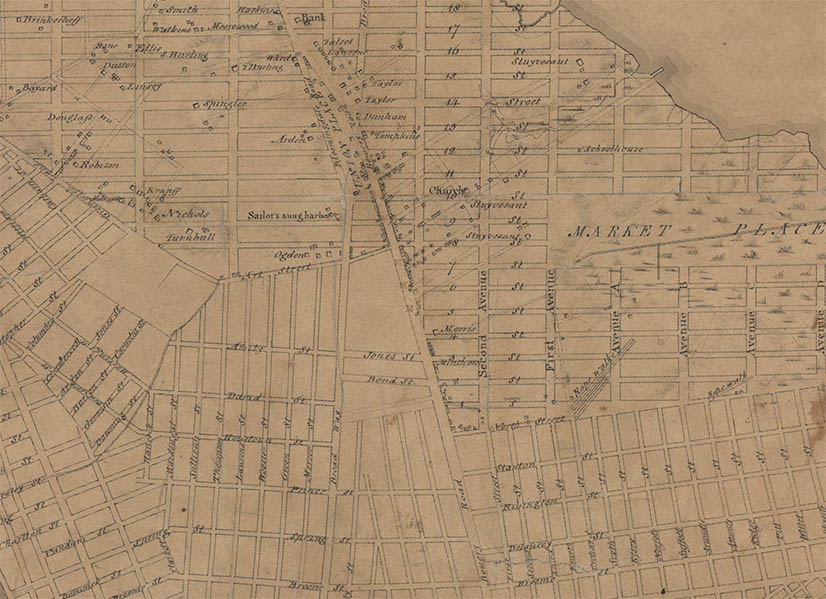

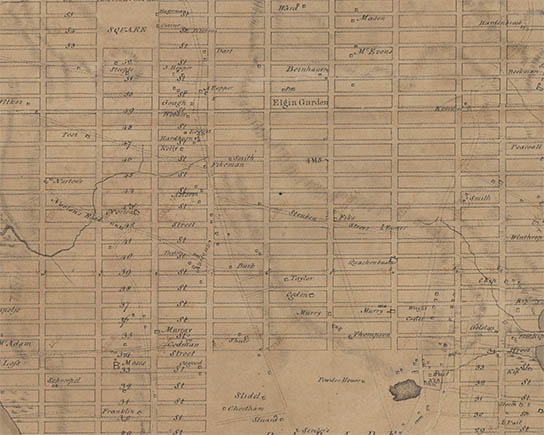

This detail from John Randel’s original pen and ink map of the Commissioners’ 1811 street survey shows the “intersection” (pun intended) of the existing New York street plan (Greenwich Village, left) with the proposed grid (starting with 1st street in the Lower East Village, center, right). It is a glance of both the past and the future of New York City.

Nieuw Amsterdam, the first permanent European settlement on Manhattan, was founded by the Dutch in 1624. Fort Amsterdam was built in 1625 and a northern rampart1 spanning the island between the East and Hudson Rivers was built in the 1640s.

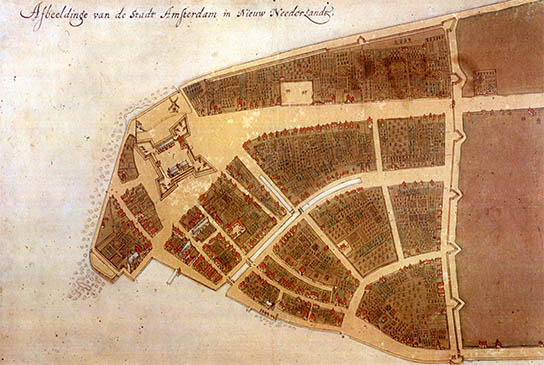

Between 7 Jun–7 Oct 1660 surveyor general Jacques Cortelyou made a stake survey of the city. His map, the Afbeeldinge van de Stadt Amsterdam in Nieuw Needersandt (AKA the Castillo Plan), includes some 15 roads (depending on how you count them) and nearly 300 houses.2 It was the first reasonably detailed plan of the settlement:

Detail, the Castillo Plan. NAHC

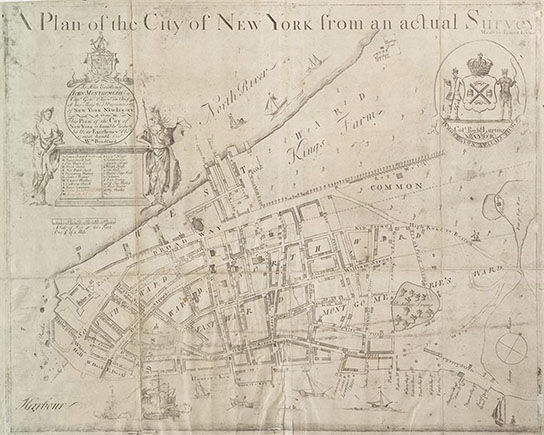

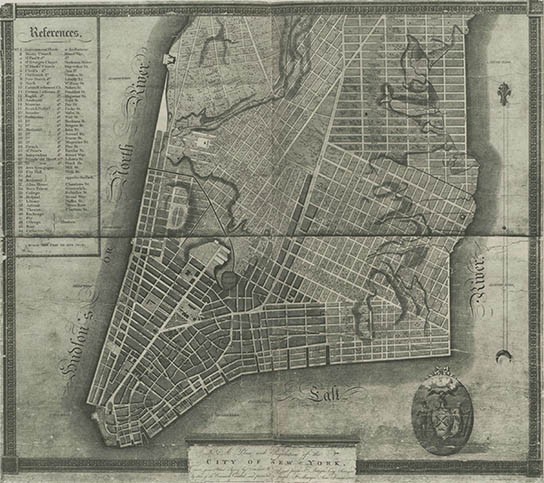

This copperplate engraving printed by Thomas Bradford in 1730 was based on a survey by James Lyne. The Bradford map was the first of New York actually printed in the city, which by this time had a population of 8000 and a street grid extending as far north as present-day Fulton Street.3

The Bradford Map. NYPL

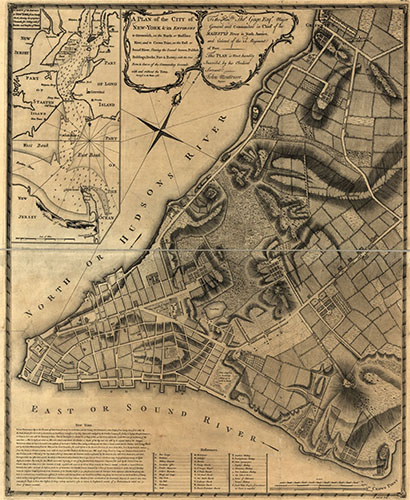

The Royal engineer Lt. John Montressor produced this map between 7 Dec 1765 – 8 Feb 1766. Although he had to survey sub rosa (under threat of unruly Stamp Act mobs) it was nevertheless the most accurate map of the city until the Ratzer Plan of 1770.4 It shows a city of 12,500 with a street grid extending as far north as present-day Soho:

The Montressor Map. LOC

As these maps make clear the layout of the city evolved into, to be kind, something of a mess. The tangled jumble of narrow, irregularly platted streets and small, densely-packed lots made, e.g., fire control or epidemic prevention nearly impossible. As the population dramatically grew after the Revolutionary War it became evident that some sort of civic planning was needed.

In 1797 the city council commissioned the architect Joseph-François Mangin and the surveyor Casimir Goerck to prepare a survey of the existing streets. It took Mangin four years to complete his Plan and Regulation of the City of New York. The map included not only the existing streets but his own fanciful proposed grid. As he said it was not “the plan of the city such as it is, but such as it is to be.” The plan obviously alarmed landowners and facing universal protest the city abandoned the idea in 1803.

The Mangin-Goerck Plan, from ref. 5

On 3 Apr 1807 the city council, with legislative support from Albany, appointed Gouverneur Morris, John Rutherfurd and Simeon De Witt to the Commission of Streets and Roads to establish a comprehensive street plan for Manhattan. Or more specifically to “[lay] out Streets... in such a manner as to unite regularity and order with the public convenience and benefit and in particular to promote the health of the City...” The commission appointed John Randel, Jr., as its chief engineer and surveyor and they began a survey of the island marking each proposed intersection in their plan with marble monuments or iron bolts.

Of course their efforts were not well received by “vexatious” landowners. Markers were removed, requiring resurveys, and work crews were sued for property damage or arrested by the Sheriff for trespassing. On one occasion Randel even noted that “[we] were pelted with cabbages and artichokes until [we] were compelled to retreat in the exact reverse of good order.”

Despite the many difficulties the Commission completed their plan by early spring 1811. Randel prepared a monster-size (100 × 30") pen and ink map which was filed 30 Mar and accepted by Mayor Dewitt Clinton on 4 May.

The Randel map

Detail, present-day Times Square

As early as May 1811 William Bridges, architect and city surveyor, was offering an engraved map that was an identical (and uncredited) copy of Randel’s survey: 6

The Bridges map. LOC

Detail, present-day Times Square

The Commissioners’ plan consisted of 12 lettered or named north-south streets running parallel to the island and 155 numbered east-west cross streets in a perfectly orthogonal grid – a life-size cartesian coordinate system.

The idea of a street plan was certainly not new, consider Penn’s 1682 layout of Philadelphia or L’Enfant’s 1791 plan of Washington D.C., but no municipality applied their plan as ruthlessly and as relentlessly as New York did over the next century. And that is a topic for part II.

1. The street next to the 12-ft earthen rampart was named de Waal Straat (either after the wall itself or after the Walloon family – pioneer settlers in New Amsterdam). In 1685 English surveyors laid out a new road along the original outline of the rampart. The road is now known as – and I’m sure you already guessed this – Wall Street. Here is a 23 Oct 2011 photo looking West toward Trinity Church:

2. The original map was found in the early 1900s bound into another atlas originally owned by Cosimo III de’ Medici at the Villa di Castello near Florence, hence the name. The Castillo plan is significant not only for the map, but for Nicasius de Sille’s 10 Jul 1660 census. Comparing the Plan to the list it is possible to identify most of the buildings residents. All of this is covered in Joycean-like detail in vol. 2 of I. N. Phelps Stokes seminal The Iconography of Manhattan Island, 1498–1909. (New York: Robert H. Dodd, 1915– 1928). All six volumes are available at Columbia University’s CLIO server.

3. For more information see: Andrews, William L. James Lyne’s Survey Or, As It Is More commonly Known the Bradford Map. New York: Dodd, Mead and Company, 1900 which is available at CLIO.

4. For an analysis of Revolutionary War-era maps of New York see: Cumming, W.P. “The Montresor-Ratzer-Sauthier Sequence of Maps of New York City, 1766–76.” Imago Mundi. 1979; 31: 55–65.

5. Plate 70 from vol. 1 of Phelps Stokes’ The Iconography of Manhattan Island, 1498–1909. See note 1.

6. Bridges’ map was beautifully engraved by Peter Maverick and published by Isaac Riley. It was available as individual sheets or as a complete 6-sheet 91 × 24" map. The most extravagant version was a varnished, hand-colored, linen-backed map mounted on wooden rollers (USD 15.50).

Randel announced his own map (which unfortunately was never published) in a 21 Mar 1811 letter to the New York Evening Post suggesting that it “...will be found on examination to be more correct than any that has hitherto appeared.”

Bridges was less than happy with this development and responded on 29 Mar: “Observing in Mr. Randell’s advertisement of his Map of Manhattan Island a direct and illiberal attack on my Map... I feel compelled reluctantly to say a few words on what I consider unprincipled, and most assuredly unprovoked conduct.”

Randel followed up on 29 Mar: “You must know that your observations, dated March 24th, and addressed “to the public,” are as unjust as they are severe.” He went on at length to defend his map and surveying methods and point out the errors in Bridges map and closed with “P, S. I will furnish you with a list of the above errors if you should desire it.”

The entire play-by-play is covered in Vol 3 of Phelps Stokes Iconography.

21 Nov 2011 ‧ Cartography