68

The Art and History of Illumination

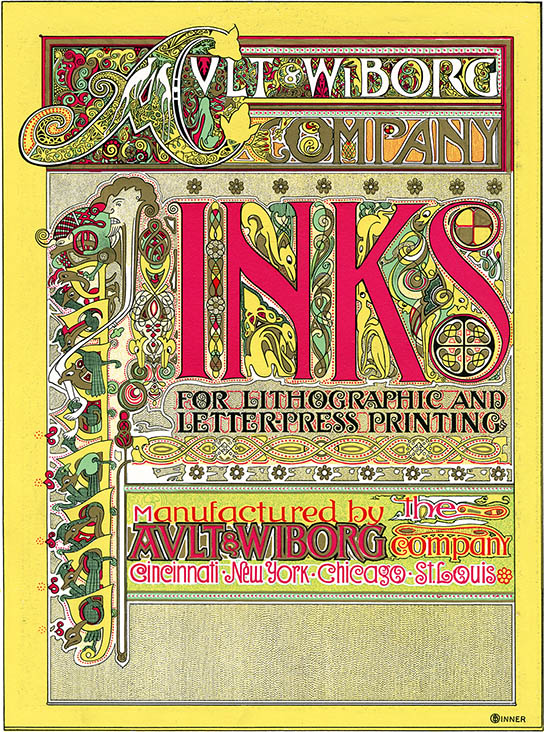

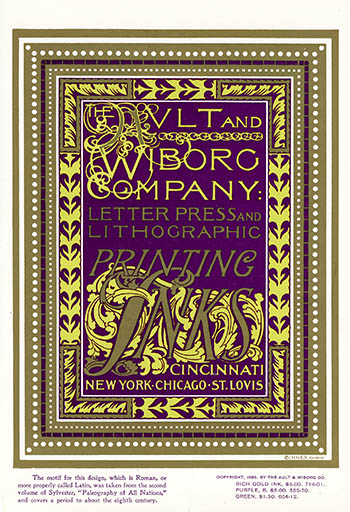

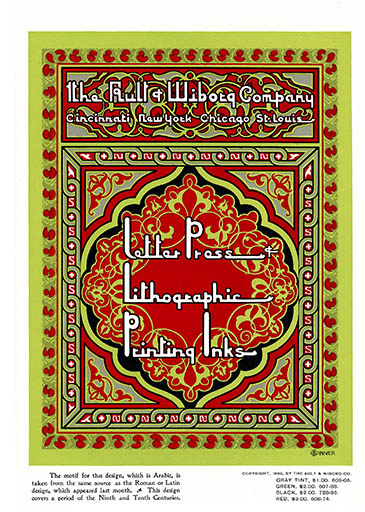

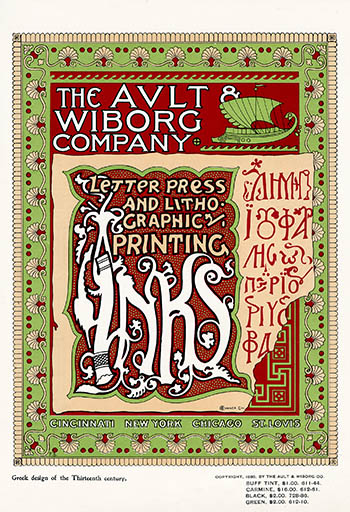

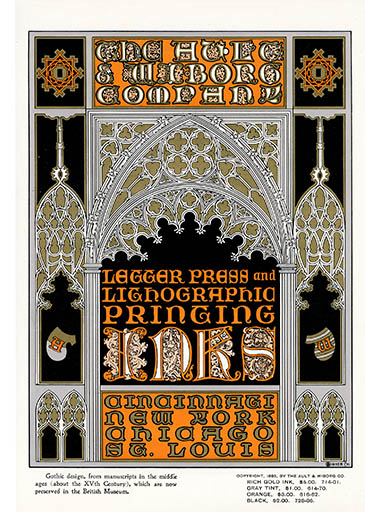

The Ault & Wiborg Poster Album

In 1876 Levi Addison Ault (24 Nov 1851 – 6 Feb 1930), the son of a French-Canadian cloth manufacturer, become a lampblack merchant in Cincinnati. Just two years later, along with his best salesman Frank Bestow Wiborg (30 Apr 1855 – 12 May 1930), he began a much more ambitious enterprise – an ink company. The Ault & Wiborg company, makers of lithographic and letterpress inks, was founded in July 1878 and incorporated in 1891.1

The company initially produced a range of colored inks from coal tar dyes. In a classic case of “at the right place at the right time” demand for their inks rose almost geometrically as color lithography replaced letterpress in popular advertising and art. By the turn of the century they were one of the world’s largest ink suppliers.

Following their motto Hic et Ubique (Here and Everywhere) they established offices not only in Cincinnati but in New York, Chicago, St. Louis, Buffalo, Philadelphia, San Francisco, Toronto, Havana, the City of Mexico, Buenos Aires, London and Yokohama.

Wiborg withdrew from active management in 1906 but Ault continued with the company until 1928.2 Over the years the company developed inks, dyes and varnishes for rotogravure, steel die and mimeograph. They even produced carbon paper and typewriter ribbons.

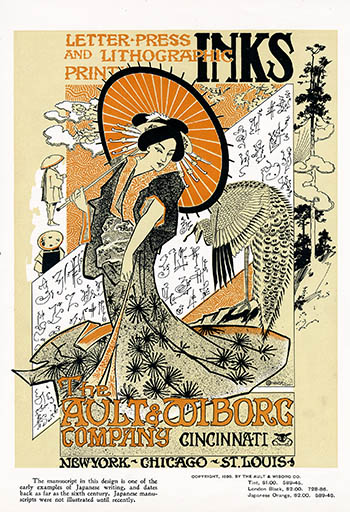

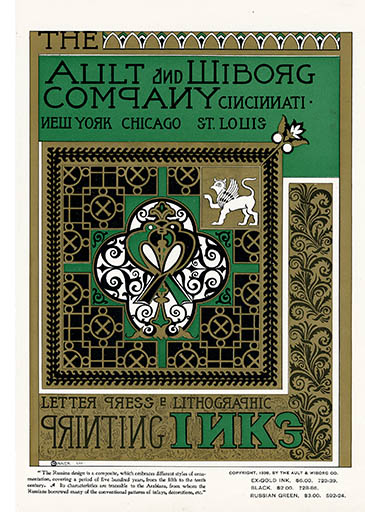

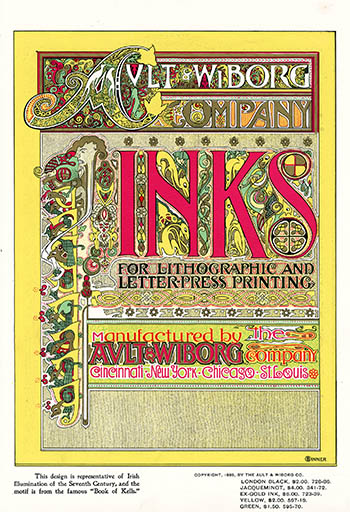

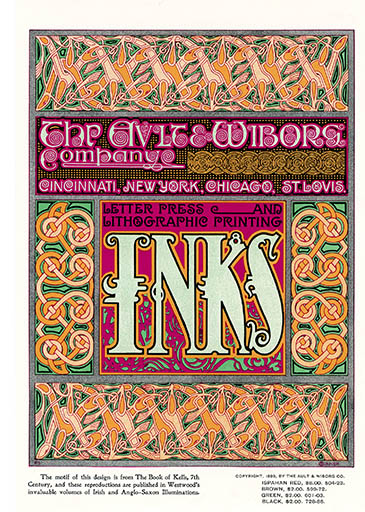

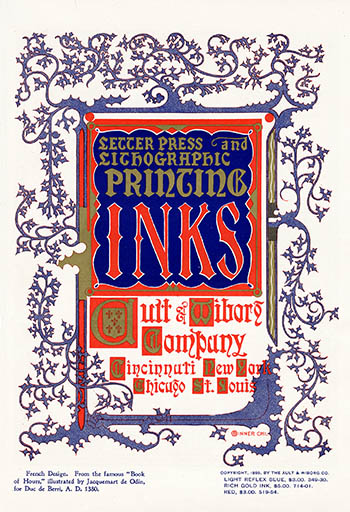

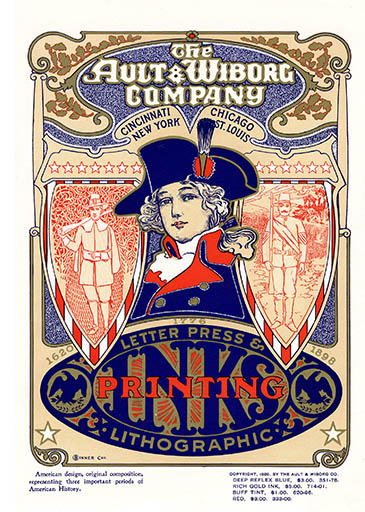

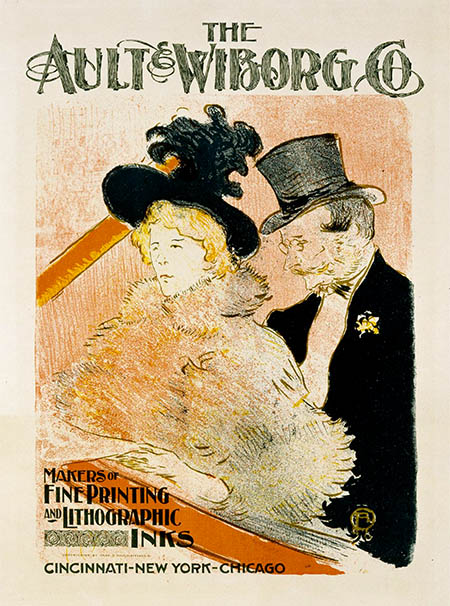

Around 1895 Ault & Wiborg began placing full-color lithographic advertising posters in trade publications such as The Inland Printer, The Engraver and Printer and The American Printer. With their considerable resources they hired some of the best commercial artists of the day, including Will Bradley (see part I) and Henri Toulouse-Lautrec.3

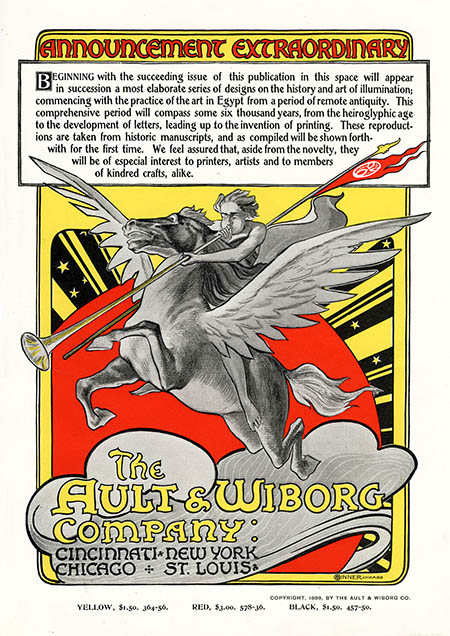

The ad that advertised the subsequent series of ads, Jul 1898

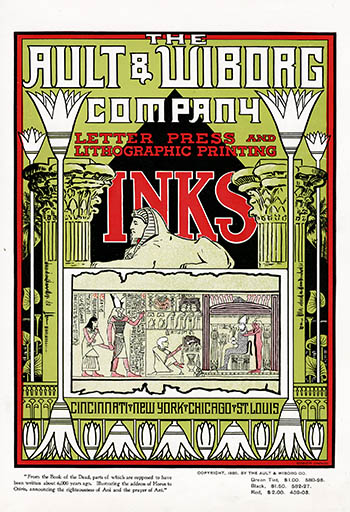

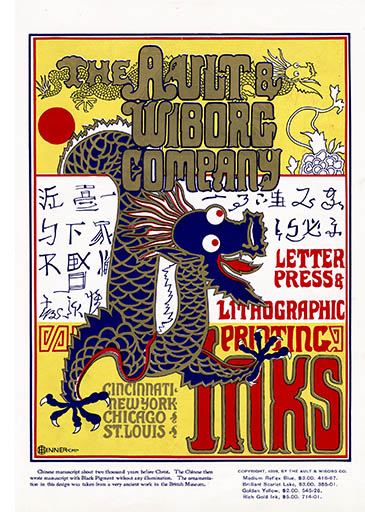

Needless to say other ink companies, including their crosstown arch-nemesis the Queen City Ink Company, also began to place full-color ads in the trade magazines. Perhaps to separate them from their competitors Ault & Wiborg commissioned the Chicago advertising pioneer Ocsar Binner and his Binner Engraving to design a series of ads covering the history of illumination. The idea, as Binner himself states in PR release thinly veiled as an editorial, was:

“To call to the notice of possible purchasers the products of an ink factory, it is manifestly important that the colors should in some way be shown. In no better way could this be done than by inaugurating a series of unique designs, which would not only be attractive and enable the inkmakers to show their products advantageously, but at the same time be instructive to those who watch the pages of the trade publications in which the advertisements are placed.” 4

The 13 ads, illustrated by Frank W. Swick, ran between Jul 1898 – Aug 1899 in several magazines.5 They were, not surprisingly, rather popular with an audience of printers and designers and soon Ault & Wiborg was overwhelmed by reprint requests. The company responded by compiling a selection of their lithographs into the Ault & Wiborg Poster Album.6 Among the Album’s 60 plates was the entire illumination series as well as all 20 of their Bradley commissions.

Binner later attempted the same idea again with other ink companies, notably with the Jaenecke Printing Ink Co. Ault & Wiborg continued to commission lithographic posters for at least the next ten years.

1. For more historical and technical details about the company see Robert Baptista’s ColarantsHistory. Honestly, how can you not love a site devoted to the history of chemical dyes and pigments?

2. It should go without saying that Both Ault and Wiborg became wealthy industrial titans. By 1910 Ault had homes in San Francisco, Havana, Mexico City and Paris. He sold his share of the company in 1928 for 14 million USD. He was also an avid naturalist and the chairman of the Cincinnati Parks Board from 1908–1926. He and his wife donated 204 acres of land to the city to create Ault Park. It was one of two parks named after him.

Wiborg and his wife became international travelers and he even wrote a book about it: Wiborg, Frank. A Commercial Traveller in South America. New York: McClure, Phillips and Co., 1905 (which is available on Google Books). The Wiborgs were one of the first families to build in the East Hamptons. Wiborg beach, on the Gardiner Peninsula and seaside to the Maidstone Club is named in his honor.

Wiborg's oldest daughter, Sara Sherman Wiborg and her husband Gerald Clery Murphy, as expatriates living in Paris in the 1920s, became “the golden couple of the lost generation.” They were photographed by Man Ray, written about by Fitzgerald and Hemingway, and painted by Picasso (well, at least Sara was). For more see: Tomkins, Calvin. Living Well is the Best Revenge. New York: Viking, 1971, or Valii, Amanda. Everybody Was So Young: Gerald and Sara Murphy: A Lost Generation Love Story. New York: Houghton Mifflin, 1998.

3. Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec’s famous Au Concert poster depicted Emilienne d’Alencon and Gabriel Tapie de Celeyran at the Cabaret des Decadents. The 5-color brush and splatter print was prepared as a zinc-plate lithograph for export to America where the lettering was added by an anonymous hand. It was his only American commission. The poster has been reprinted countless times, most notably in Chéret's seminal Maîtres de l'Affiche. The original plate is now in the Art Institute of Chicago.

4. “Modern Advertising Methods.” The Inland Printer. 1899 Aug 23(5): 607.

5. The Inland Printer Jul 1898 21(5) – 1899 Aug 23(5), or The Printer and Bookmaker 1898 Mar 21(6) – 1899 Aug 2(6). I am sure that the series ran in other trade publications as well.

6. The Ault & Wiborg Poster Album. Cincinnati: Ault & Wiborg, 20 May 1902. Good luck, seriously, on finding one of these. Most extant copies have been pieced out into individual plates by poster dealers. The going rate for one in good condition is now about 2500 USD, or 833× the original postpaid price.

28 Jun 2010 ‧ Design