The Ault & Wiborg Poster Album

The American Art Nouveau Ad

Levi Addison Ault was born on November 24th, 1851 in Mille Roches, Ontario to the cloth merchant Simon Ault and his wife Caroline. He was the sixth of seven children. At the age of 17 Levi left with one of his older brothers to seek his fortune in America and spent the next five years as a bookkeeper in Wisconsin. He then followed his brother to Cincinnati where he took a job with a lampblack, pitch and rosin merchant and soon became their best salesman. Two years later, applying what he learned about the lampblack business, he began a new enterprise—selling printing ink.

Frank Bestow Wiborg was born in Cleveland on April 30th, 1855 to the Norwegian immigrant dockhand Henry Paulinus Wiborg and his wife Susan. Henry died of pneumonia when Frank was only 12 and his mother soon remarried. Frank didn’t get along with his new stepfather so he left for Cincinnati and somehow managed to gain admittance to the select college-prep Chickering Institute, where, according to his family, he paid his way through school by peddling newspapers. After his graduation in 1874 he went to work for Ault’s fledging ink concern. Restless, dynamic and smart, he soon impressed Levi with his work ethic.

With Levi’s knowledge of the ink trade and an investment from Frank the two formed the Ault & Wiborg Company in July, 1878 with the intention of becoming “the top producer and distributor of inks and lithograph supplies in America, perhaps the world.”

And that’s pretty much exactly what happened.

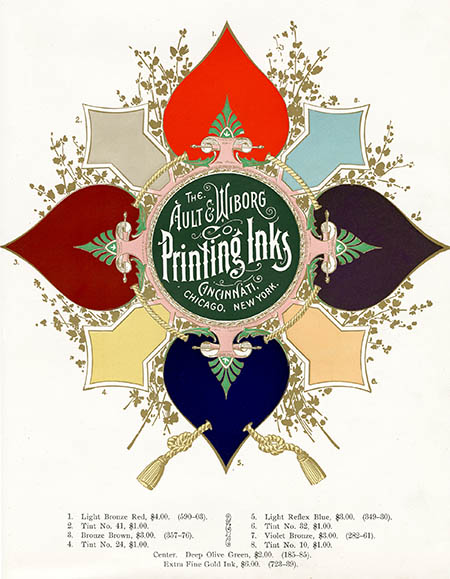

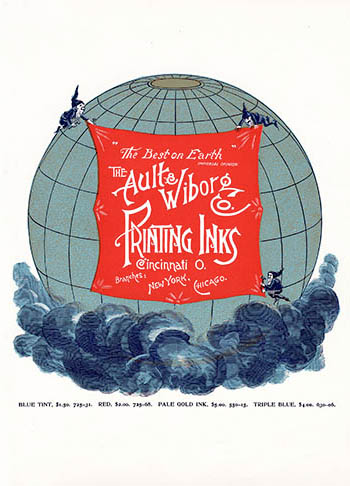

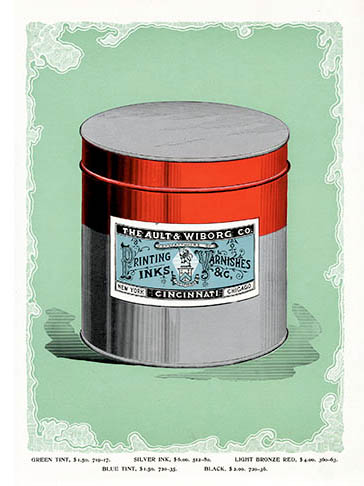

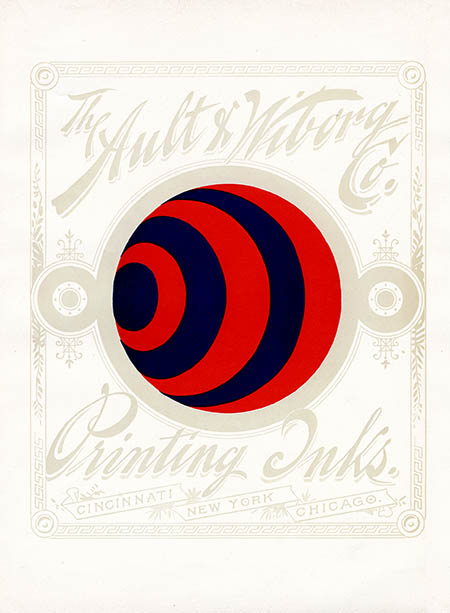

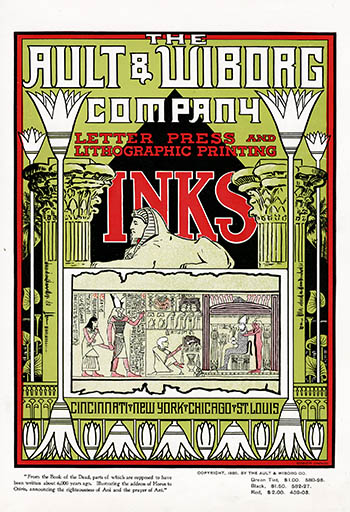

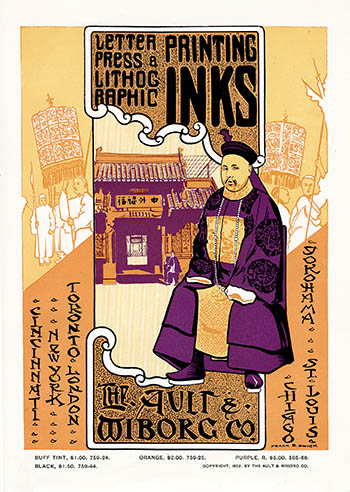

Around 1890 the company hired a German-trained chemist and they began developing an extensive range of coal tar-based inks and dyes, including a novel series of reds and blues (Reflex Blue). In a classic case of “at the right place at the right time” demand for Ault & Wiborg’s inks rose almost geometrically as color printing replaced letterpress in popular graphics. By 1895 they were advertising that their Cincinnati factory was doing more business than all other printing ink factories west of the Alleghenies, combined. They not only established offices in New York, Chicago, St. Louis, Philadelphia and San Francisco but, following their motto of Hic et Ubique (Here and Everywhere), offices in cities as far-flung as Toronto, Havana, Buenos Aires, London, Paris and Yokohama. By the early 1900s they had, indeed, became the largest ink company in the world.

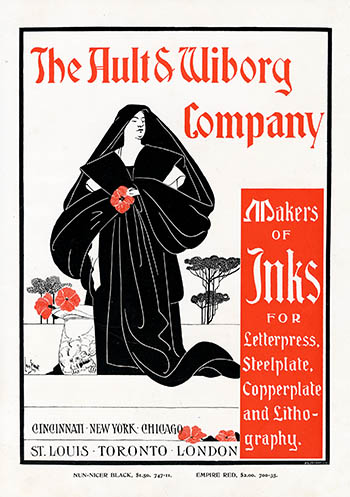

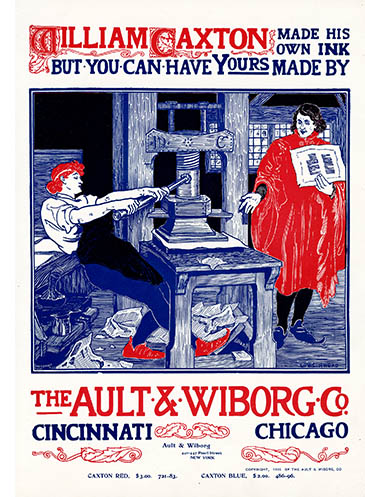

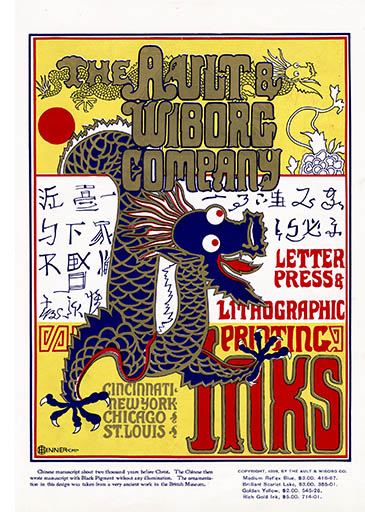

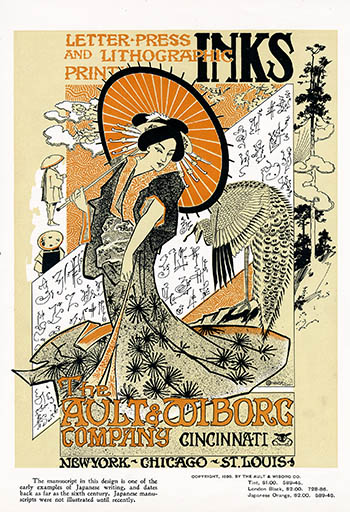

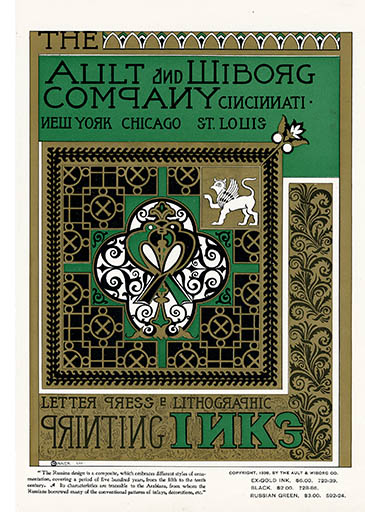

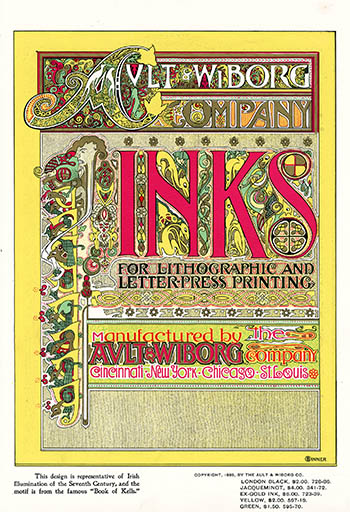

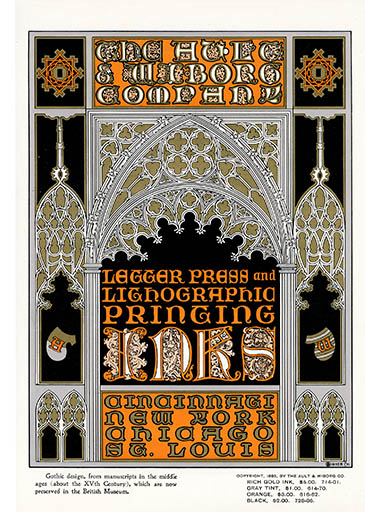

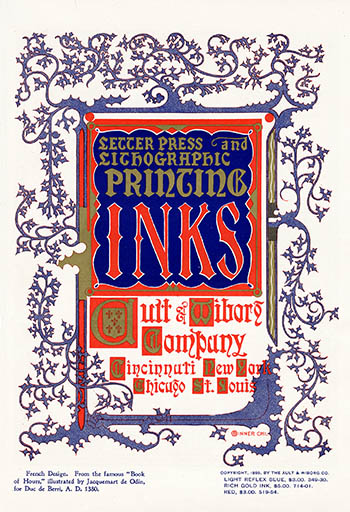

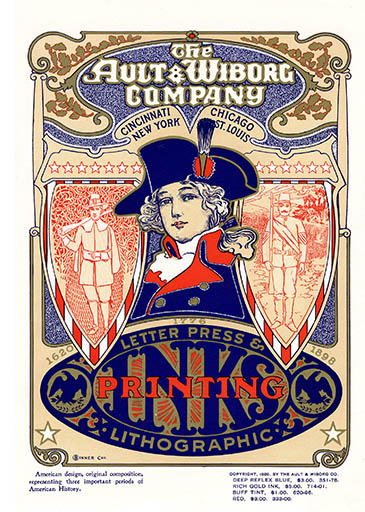

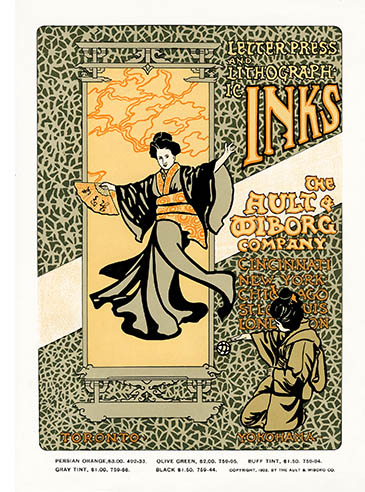

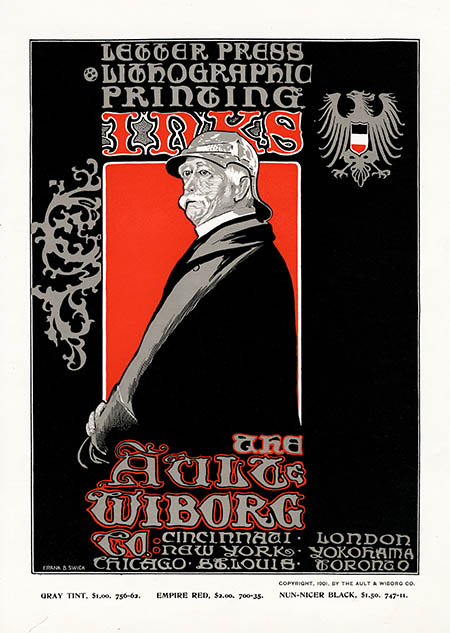

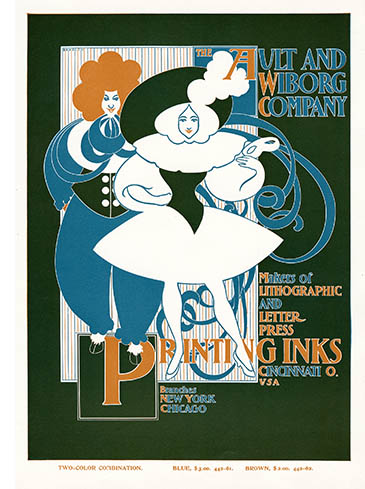

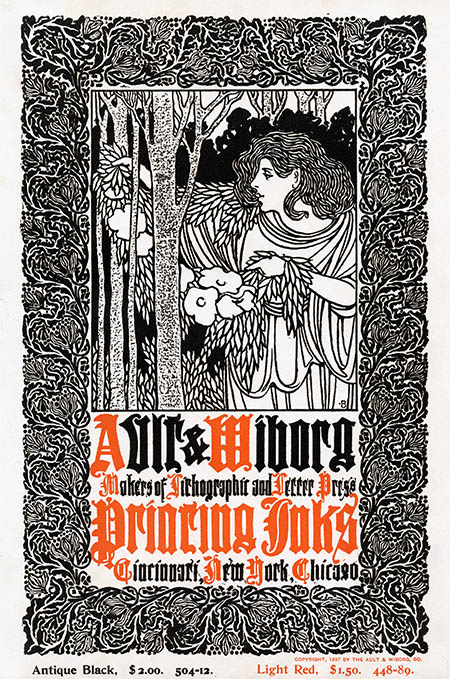

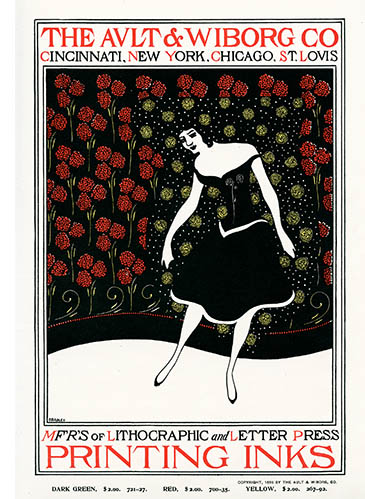

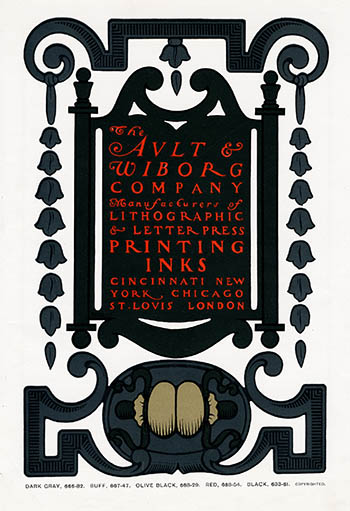

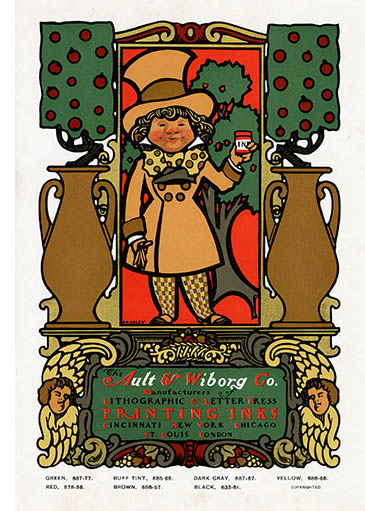

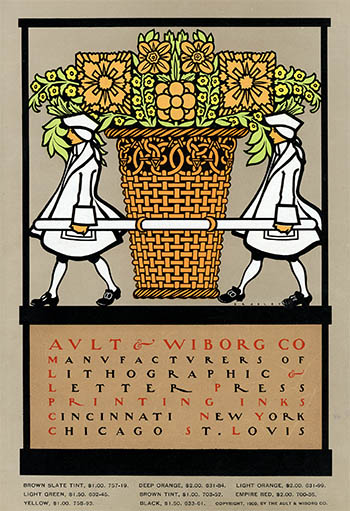

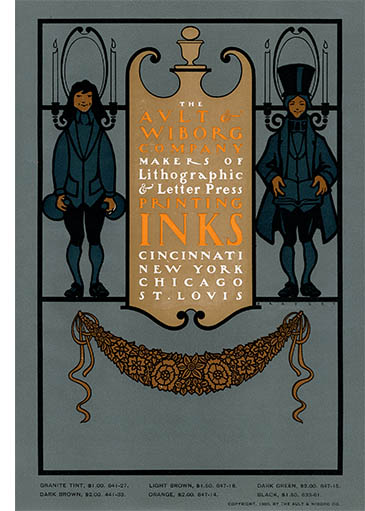

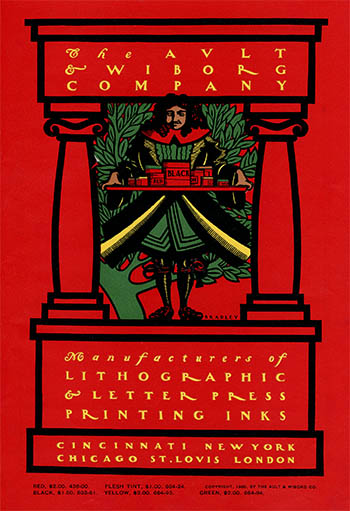

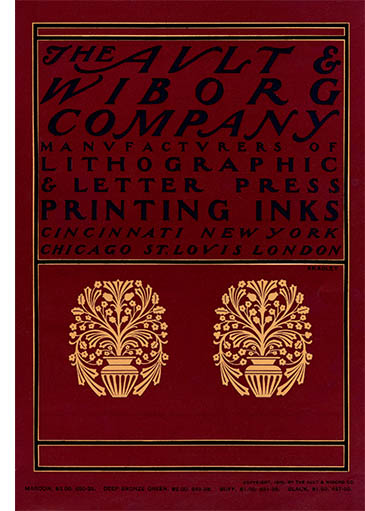

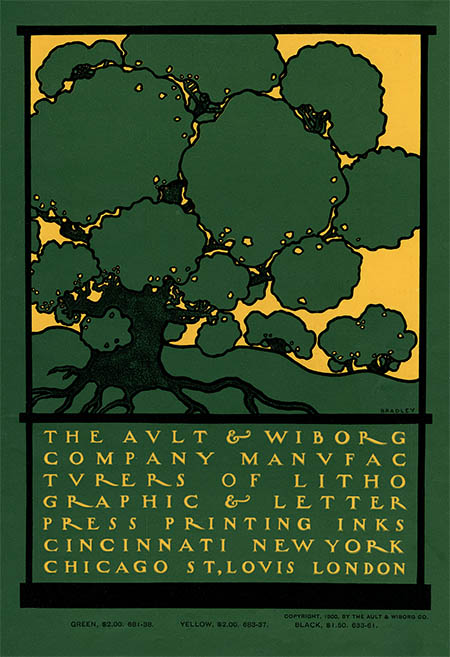

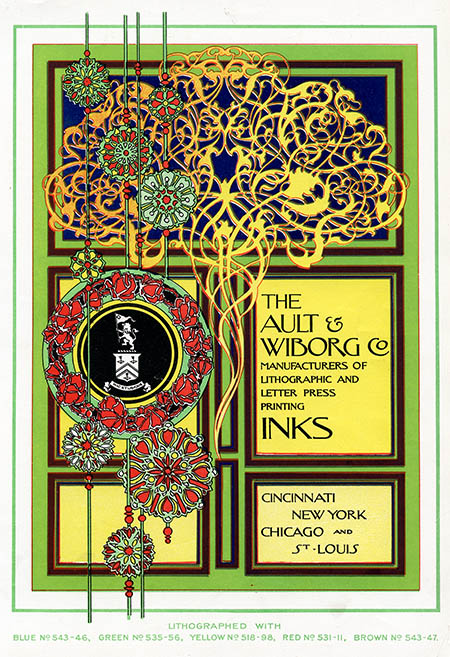

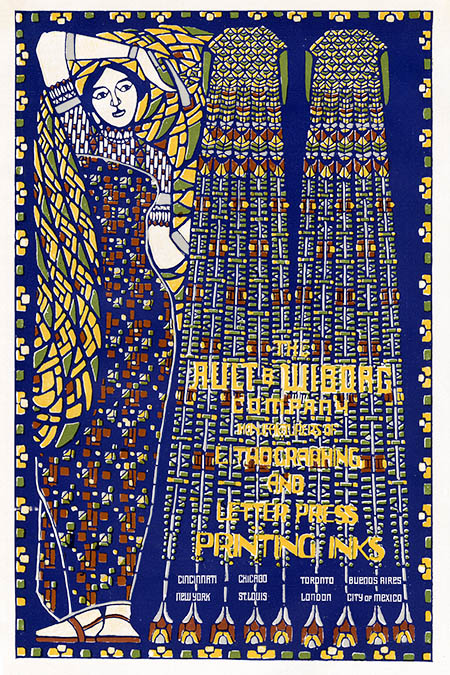

As early as 1890 they began running single-color poster inserts in trade publications such as The Inland Printer, The Printer and Bookmaker and The American Book- maker. The posters became progressively more complex and by 1892 they were preparing ads with as many as 16 colors. These letterpressed ads, printed with the very inks they were advertising, were not only masterful examples of presswork but high points in late Victorian and early Art Nouveau design.

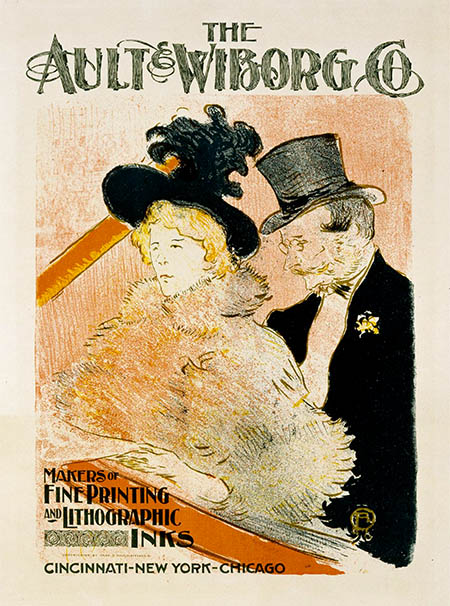

Of course they weren’t the only ink company around and their competitors, especially their cross-town rival, The Queen City Ink Company, were also perfectly capable of producing color ads using their own inks. To separate themselves from their competition they asked Henri Toulouse-Lautrec (who supposedly favored their inks) to illustrate an ad. His brush-and-spatter zinc-plate lithograph of Emilienne d’Alencon and Gabriel Tapie de Celeyran at the Cabaret des Decadents was his only American commission.

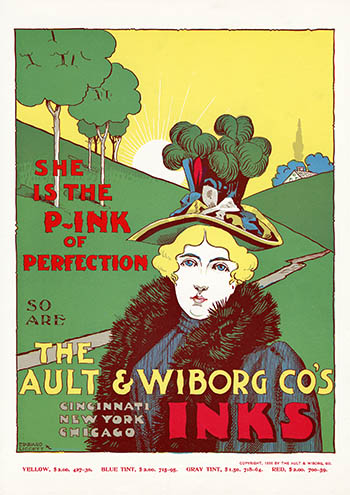

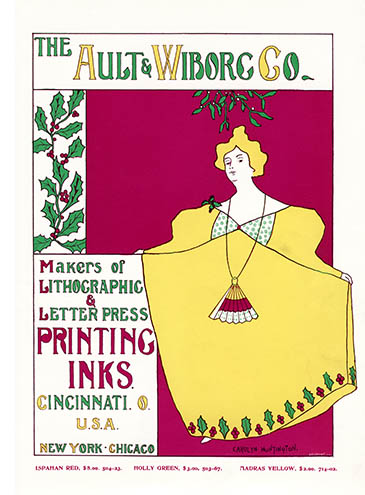

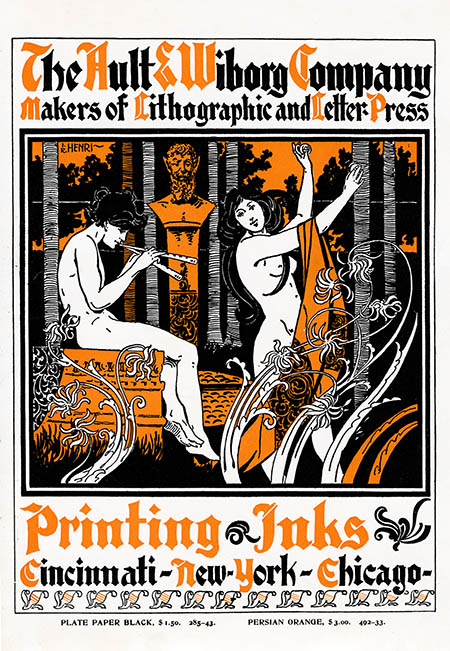

After the Toulouse-Lautrec poster, Ault & Wiborg began commissioning ads from American artists and illustrators including Edward Liggett, Carolyn Huntington, Robert Henri and Louis Rhead:

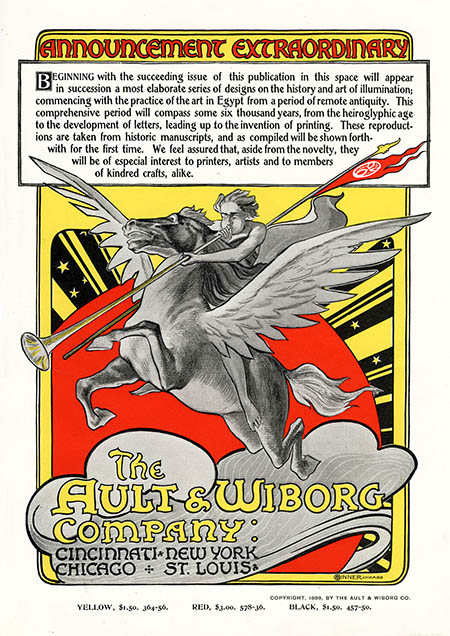

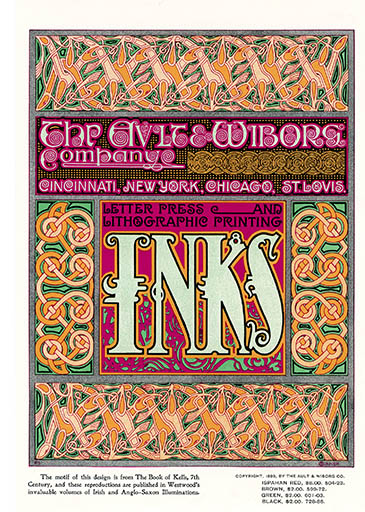

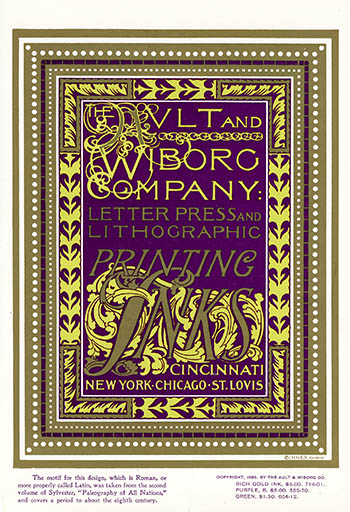

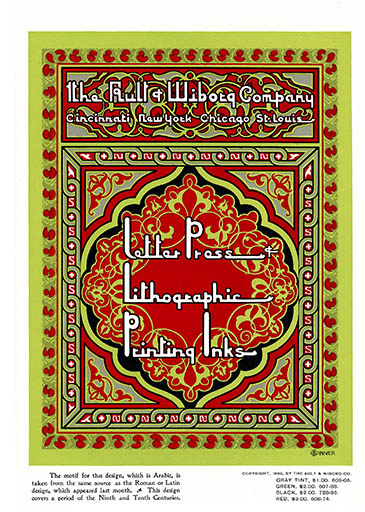

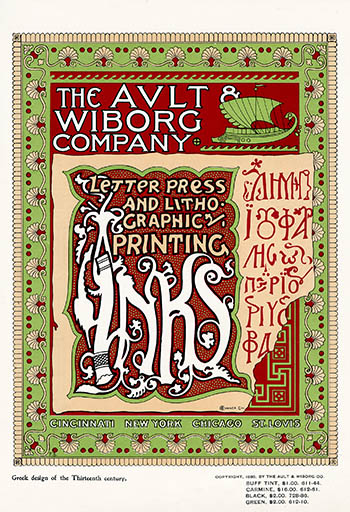

Again, they weren’t to only ink company who could hire popular commercial illustrators, so with the help of the Chicago advertising pioneer Oscar Binner, they commissioned a series of ads covering the history of illumination. The 13 ads, illustrated by Frank Swick, ran in several publications between July 1898–August 1899. The idea, as Binner wrote in a press release thinly disguised as an editorial, was:

“To call to the notice of possible purchasers the products of an ink factory, it is manifestly important that the colors should in some way be shown. In no better way could this be done than by inaugurating a series of unique designs, which would not only be attractive and enable the inkmakers to show their products advantageously, but at the same time be instructive to those who watch the pages of the trade publications in which the advertisements are placed.”

The Illumination series was so successful that other ink manufacturers, notably the Jaenecke Ink Company, the Queen City Ink Company and the Cooper Ink Company followed suit (although, perhaps, with less success). Swick, after his work on the series, became a regular artist for the company:

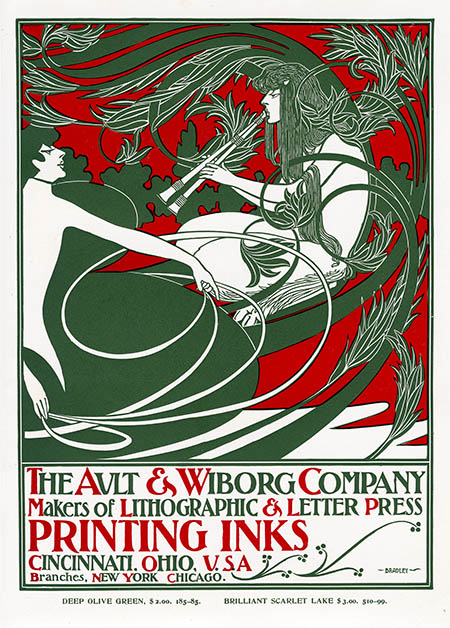

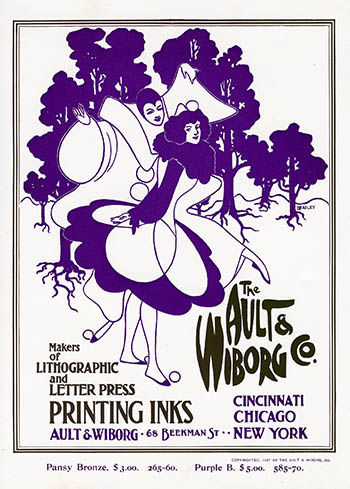

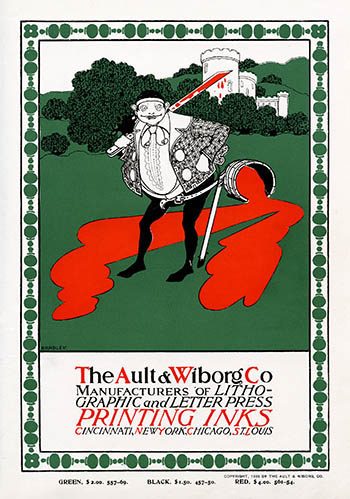

Of all their illustrators, however, it was Will Bradley—the dean of American design and an artist their competitors could ill afford—who would create their most memorable advertising. Between 1897–1900 he did no less than 20 ads for the company. Bradley’s work for Ault & Wiborg covered the entire range of his interests—everything from Beardsley-inspired Art Nouveau to Morris-inspired Arts and Crafts to Franklin-inspired Colonial printing.

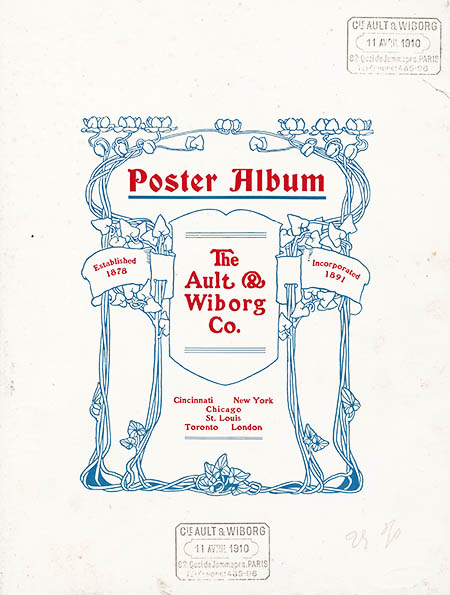

The poster ads proved so popular, both within the industry and with the general public, that the company was soon having a hard time keeping up with requests for copies. After they ran out of loose sheets they decided to reprint a selection of their ads in The Ault & Wiborg Poster Album. As The Inland Printer wrote in August, 1902:

“Readers of The Inland Printer who have watched with so much interest the attractive inserts of the Ault & Wiborg Company, will be pleased to learn that the firm has had a complete set of the sheets printed and bound in cloth and issued them under the title of “Poster Album.” The series by Will Bradley, and the one by the Binner Engraving Company giving the history and art of illumination, are the gems of the collection, but a number of other exceedingly striking and effective designs are to be found in the book. It is the intention of the firm to furnish these books to friends and customers on application, but the general public and poster collectors are expected to pay $3 for the work.”

The company continued to issue full-color posters until 1913, including a series of lithographs that were all but direct copies of Jules Chéret’s work. By the beginning of World War I they returned to single-color ads and by the 1920s had essentially ceased advertising in the trade journals altogether.

Wiborg had spent much of his time with the company abroad, establishing offices in Europe, the Caribbean, South America and Asia. He became an inveterate traveller and he and his family became friends with US politicians and European royalty.1 In 1906 he sold his stake in the company and moved to New York, eventually splitting his time between a Park Avenue townhouse and an estate in the East Hamptons. He died of pneumonia in his Park Avenue home on May 12th, 1930.

Ault had been grooming his son Lee to take over the business but after Lee’s untimely death in 1918 he began selling off the company in parts. The dye business was sold to Ciba, Geigy and Sandoz in 1920 and the ink business to the International Printing Ink Corporation in 1924. As an avid naturalist, he served on the Cincinnati Park Board for 20 years and eventually donated a 200-acre parcel which became Ault Park. He died in his Cincinnati home on February 6th, 1930.

1. In 1882 Frank married Adeline Moulton Sherman, daughter of the banker Hoyt Sherman and niece of the Civil War general William Tecumseh Sherman. They had three daughters: Mary, Sara, and Olga. In 1915, while living at the Dunes, their 30-room East Hampton mansion, Sara married Gerald Murphy, the boy next door and heir to the Mark Cross leather company. The couple had three children and in 1921 they left prohibition-era New York (and the scornful eyes of their parents) for the freedom of Paris. A year later they decamped for Cap d’Antibes on the French Riviera and eventually bought a house which they named the Villa America.

Sara’s direct, candid Americaness, her flair for a party and her unusual fondness of sunbathing on the beach in her pearls soon attracted a coterie of notable French artists and American expatriates, many who saw Sara as their muse. F. Scott Fitzgerald based Dick and Nicole Diver in Tender is the Night after the couple. Ernest Hemingway wrote about them in The Garden of Eden. Archibald MacLeash based the characters in his play J.B. on them. Man Ray photo- graphed them. Fernand Léger and Pablo Picasso (who may or may not have been Sara’s lover) painted them. They became, as Amanda Valli wrote in her biography, “the golden couple of the lost generation.”

—August 3rd, 2015. Updated January 17th, 2017. Design