William Ramsdell, The Edmund Fitzgerald, 2013

The Wreck of the Edmund Fitzgerald

The Annotated Gordon Lightfoot

The Canadian singer-songwriter Gordon Lightfoot (17 Nov 1938–) was an avid recreational boater on Lake Ontario, owning a stock 39-ft Erickson sloop (Sundown) then a Victor Carpenter custom 46-ft spruce-and-fiberglass cruising sloop (the Golden Goose).

It’s no suprise then that he took particular interest in a Nov 1975 Newsweek account of the loss of the Edmund Fitzgerald. 1 He was so moved that he began writing a song as a tribute to “the ship, the sea, and the men who lost their lives that night.” Within a month he had penned what was arguably one of the greatest topical ballads ever written – “The Wreck of the Edmund Fitzgerald.” 2

Here are the original song lyrics, lightly annotated:

The legend lives on from the Chippewa 4 on down

of the big lake they called Gitche Gumee.5

The lake 3 it is said, never gives up her dead 7

when the skies of November turn gloomy.6

With a load of iron ore twenty-six thousand tons more

than the Edmund Fitzgerald weighed empty,10

that good ship and true was a bone to be chewed

when the Gales of November came early.11

The ship was the pride of the American side 8,9

coming back from some mill in Wisconsin.

As the big freighters go, it was bigger than most

with a crew and good captain well seasoned.

Concluding some terms with a couple of steel firms

when they left fully loaded for Cleveland,10

and later that night when the ship’s bell 20 rang,

could it be the north wind they’d been feelin’? 11

The wind in the wires made a tattle-tale sound

and a wave broke over the railing.

And ev’ry man knew, as the captain did too

’twas the witch of November come stealin’.

The dawn came late and the breakfast had to wait

when the Gales of November came slashin’.

When afternoon came it was freezin’ rain

in the face of a hurricane west wind. 12

When suppertime came the old cook came on deck sayin’.

“Fellas, it’s too rough t’feed ya.”

At seven pm a main hatchway caved in; he said,

“Fellas, it’s been good t’know ya!” 15

The captain wired in he had water comin’ in

and the good ship and crew was in peril.13,14

And later that night when its lights went outta sight

came the wreck of the Edmund Fitzgerald.15

Does any one know where the love of God goes

when the waves turn the minutes to hours? (ed. note–No)

The searchers all say they’d have made Whitefish Bay

if they’d put fifteen more miles behind ’er.16,18

They might have split up or they might have capsized;

they may have broke deep and took water,19

and all that remains is the faces and the names

of the wives and the sons and the daughters.21

Lake Huron rolls, Superior sings

in the rooms of her ice-water mansion.

Old Michigan steams like a young man’s dreams;

the islands and bays are for sportsmen.

And farther below Lake Ontario

takes in what Lake Erie can send her,

and the iron boats go as the mariners all know

with the Gales of November remembered.

In a musty old hall in Detroit they prayed,

in the Maritime Sailors’ Cathedral.17

The church bell chimed ’til it rang twenty-nine times

for each man on the Edmund Fitzgerald. 21

The legend lives on from the Chippewa on down

of the big lake they call Gitche Gumee.

“Superior,” they said, “never gives up her dead

when the gales of November come early.”

1. Gaines, James and Lowell, Jon. “Great Lakes: The Cruelest Month.” Newsweek. 24 Nov 1975, 48 (online).

2. Lightfoot, Gordon. The Wreck of the Edmund Fitzgerald b/w The House You Live In. (Moose Music Ltd.) Reprise Records RPS 1369, Aug 1976. The single was from the album Summertime Dream. Reprise MS 2246, Jun 1976. The song peaked at #2 on the Billboard Hot 100 on 20 Nov 1976.

German single, Oct 1976

THE LAKE

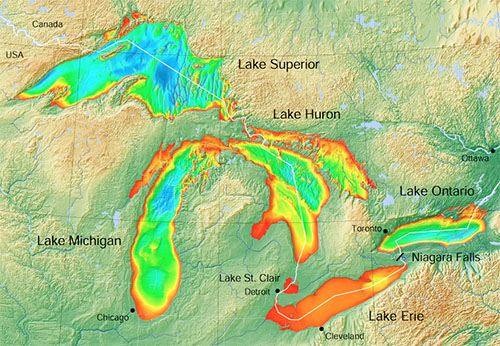

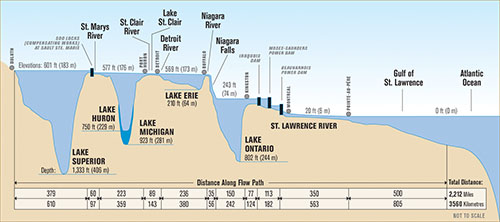

3. When the mile-thick Laurentide Ice Sheet retreated over the Mid-Continental Rift some 10,000 years ago it gouged out huge basins that filled with glacial melt creating the Great Lakes.

General bathymetry, 2015. Wikimedia Commons

Great Lakes System Profile. Michigan Sea Grant

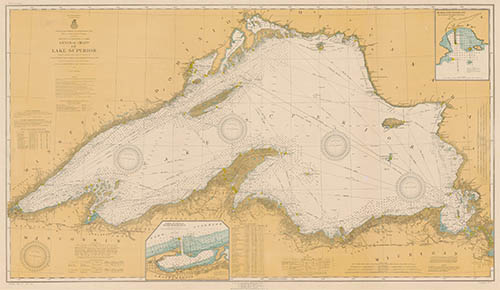

Lake Superior, the largest of the Great Lakes, contains nearly 10% of the world's fresh water (second to only Lake Baikal) and is big enough to include all of the other Great Lakes with a couple of extra Lake Eries thrown in. See: Grace, Lee Nute. Lake Superior. Indianapolis: Bobbs-Merrill, 1944 (WorldCat).

U.S. Army General Chart, 1917

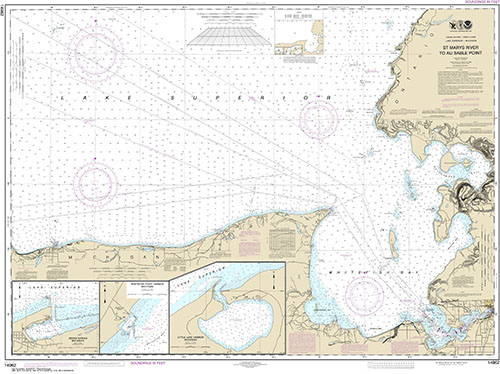

NOAA Chart 14962, 2015

4. After the Ice Age the area around Lake Superior was populated by several tribes including the Plano, the Laurels, the Woodlands and finally the Chippewa. The Chippewa, or more properly the Ojibwe, were originally from the Hudson Bay region and migrated along the St. Lawrence River after a prophecy, or miigis, fortold of the destruction of the tribe and their way of life if they didn’t move west. Around 1650 AD the tribe split and followed both the northern and southern shores of the lake as far west as Madeline Island. See: Densmore, Francis. Chippewa Customs. St. Paul: Minnesota Historical Society Press, 1979 (WorldCat) or Danziger, Edmund. The Chippewas of Lake Superior. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1978 (WorldCat).

5. The Ojibwe spoke Anishinaabemowin-Anishinaabe, one of the Algonquian languages. The phrase “Gitche Gumee” is an anglicized version of “gitchi-gami” or “kitchi-gami” which translates as “be a great sea.” “Gitche Gumee” was first used by Henry Wadsworth Longfellow in his 1855 poem The Song of Hiawatha (online).

In 1619 the French interpreter Étienne Brûlé, who had left Champlain’s expedition to live amongst the Hurons, described a large lake north of Lake Huron and named it lac supérieur (upper lake), hence the English name – Lake Superior. See: Butterfield, Willshire. History of Brulé’s Discoveries and Explorations, 1610–1626. Cleveland: Western Reserve Historical Society, 1898 (online).

6. The Great Lakes are large enough to effect weather patterns and even the climate. They act as a massive heat sink and make summer temps cooler and winter temps warmer. Although the most well-known weather is winter lake-effect snow, the most important weather affecting shipping occurs in late fall as cold, dry air moves south/southeast from northern Canada and warm, moist air moves north/northeast from the Gulf of Mexico. When the fronts converge over the Great Lakes they can create gale and hurricane force winds, snow squalls and waves over 30 ft high. These November storms have long been referred to by the local mariners as the “Witches of November.” For a primer see: Eichenlaub, Val. Weather and Climate of the Great Lakes Region. Notre Dame, Indiana: University of Notre Dame Press, 1979 (WorldCat).

7. There have been hundreds of significant shipwrecks on Lake Superior and more than 1000 lives lost. The area around Whitefish Bay (“the Graveyard of the Great Lakes”) is especially dangerous: since the loss of the Invincible in 1818 there have been more that 250 shipwrecks in the area. Not surprisingly most of these occurred during the Oct and Nov storms. For a comprehensive list see Dave Swazye’s The Great Lakes Shipwreck File.

The bottom of Lake Superior is a constant, year-round 39°F – cold enough to inhibit the methane-producing bacteria that normally decompose a body. The result is that bodies never float to the surface. So indeed, as Lightfoot wrote, the lake truely “never gives up her dead.” For a scientific analysis see: Ayers, Laura. “Differential Decomposition In Terrestrial, Freshwater, and Saltwater Environments: a Pilot Study ” Thesis. Texas State University-San Marcos, 2010 (online).

THE SHIP

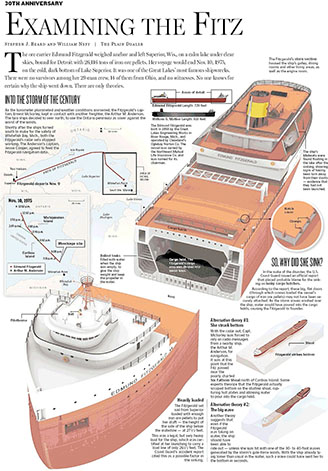

8. The S. S. Edmund Fitzgerald was conceived as a business venture of the Northwestern Mutual Life Insurance Company of Milwaukee, Wisconsin. Their plans called for a “maxiumum sized” freighter 729 ft long and 75 ft wide; i.e., as large as the Army Corps. of Engineers would allow through the Soo Locks. This infographic shows the overall construction:

On 1 Feb 1957 Northwestern contracted the Great Lakes Engineering Works of River Rouge, Michigan to build the ship. The keel (hull no. 301) was laid on 7 Aug 1957 and, using innovative prefabricated hull sections, construction was completed in only 10 months. At her launch on 7 Jun 1958 the Edmund Fitzgerald, named after Northwestern’s CEO, was the largest and most expensive lake freighter ever built. The Detroit News wrote that it was “The biggest object ever dropped into fresh water in recorded history.” For more on the early history of the ship see: Telescope. 1998 May–Aug 66(2): 47–68 (online).

Launch day

9. After successful sea trials the Fitzgerald, operated for Northwestern by the Columbia Transportation Division of Oglebay-Norton in Cleveland, began freighting iron ore in the form of taconite pellets from the Mesabi Range in northeast Minnesota to steel plants in Detroit and Toledo (hence one of her nicknames “The Toledo Express”). Over her 17-year career she made almost 750 runs and set seasonal haul records six times, often beating her own previous record. She was, indeed, as Lightfoot wrote, “The pride of the American side.” Here is an undated US Army Corp. of Engineers photo:

Here are two slide transparencies from 1971:

THE FINAL VOYAGE

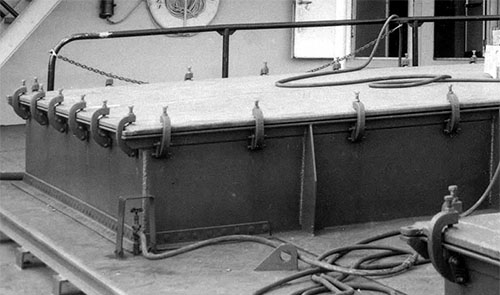

10. In the early morning hours of Sun 9 Nov 1975 the Fitzgerald – moored at the Burlington Northern Dock #1 in Superior, Wisconsin – was loaded with 51,000 gallons of diesel fuel and 26,116 long tons of taconite (or 58 million lbs, 15% more than she was originally certified for). After loading each of the 21 seven-ton rectangular hatches on the spar deck were dogged down (or maybe not, see note 19) with 68 Kestner clamps:

Detail, Fitzgerald’s hatch and Kestner clamps. 3dfitz

The Fitzgerald was bound for the Great Lakes Steel Plant at Zug Island, Michigan, where the taconite would be transformed into steel for auto parts – a 740-mile trip that should have lasted less then three days. According to some reports it was also to be her last scheduled trip before her winter lay-up in Cleveland.

Around 2:20 pm Capt. Ernest M. McSorley guided the ship into Lake Superior. At 4:30 pm the Fitzgerald was joined by by another ore freighter – the Arthur M. Anderson under Capt. Jesse Cooper, en route Gary, Indiana.

The Arthur M. Anderson, still plying the lakes, in the ice on Lake Erie, 22 Feb 2015. Boatnerd

For some book-length references on the Edmund Fitzgerald see: Schumacher, Michael. Mighty Fitz: The Sinking of the Edmund Fitzgerald. New York: Bloomsbury, 2005 (WorldCat), or Bishop, Hugh and Paquet, Dudley. The Night the Fitz Went Down. Duluth, Minn.: Lake Superior Port Cities, 2000 (WorldCat), or Hemming, Robert. Gales of November: The Sinking of the Edmund Fitzgerald. Chicago: Contemporary Books, 1981. (WorldCat), There are even more, but that’s what Google is for.

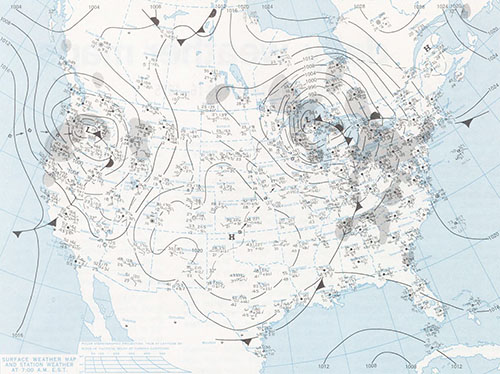

11. On 8 Nov a low-pressure system developed over the Oklahoma panhandle. As it moved across the midwest and intensified the National Weather Service predicted that it would eventually pass just south of Lake Superior. Aware of the forecast the two captains decided to take the standard downbound route. At 7:00 pm, 9 Nov the NWS issued a gale warning for the entire lake, but as Capt. Cooper recalled “at the time the gale warnings were fringe... 34–38 knots, which is not unusual for this time of year.” At 1:00 am 10 Nov the NWS upgraded the weather to a storm warning as the system passed over Marquette and the two ships plotted a new northernly course hoping that the lee provided by Isle Royale would protect them from the developing weather.

Weather map, 10 Nov 1975. NOAA Central Library Data Imaging Project

Although Lightfoot wrote “when the Gales of November came early,” historically the storm was pretty much right on time. See: Hultquist TR, et al. Reexamination of the 9–10 November 1975 “Edmund Fitzgerald” Storm Using Today’s Technology. Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society. 2006 May: 87(5); 607–622 (online).

12. The Fitzgerald first encountered the storm around 1:00 am, 10 Nov and reported NE winds of 52 knots and waves of 10 ft. McSorley radioed that he was reducing speed. To anyone who knew him this was a startling admission as he was known for “beating hell” out of the Fitzgerald and “very seldom ever hauled up [slowed down] for weather.”

During the afternoon of 10 Nov the storm center passed over the ships and by 2:45 pm sustained winds of 50+ knots were reported from the NW. The change in wind direction was an ominous development: with the wind coming off the lake there would be no lee from the Canadian shore and the fetch [the distance a wave could travel and build] was now greatly increased. For a wave dynamics primer see: Twardos, Michael. The Physics of Ocean Waves (for Physicists and Surfers). 2004 (online).

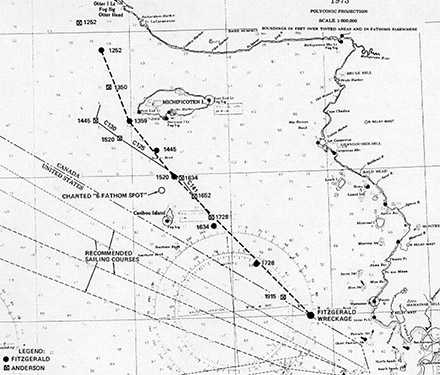

Around this time the US Coast Guard issued a warning that the Soo Locks had been closed and all ships should find safe anchorage. The Fitzgerald and Anderson charted a new southern course to seek the relative safety of Whitefish Bay:

Likely track of the Fitzgerald. From the NTSB report, ref. 19

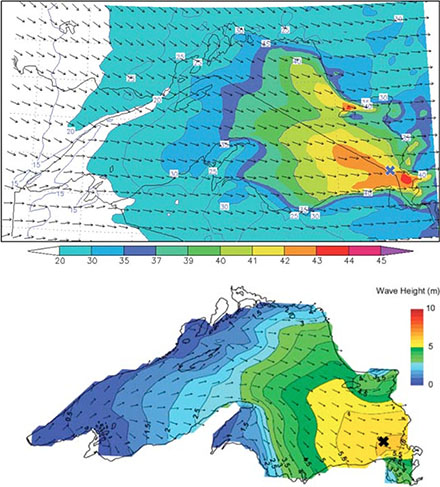

As the meteorologist Tom Hultquist (see ref. 11) noted, however, they were sailing into “precisely the wrong place at the absolute worst time:”

Wind speed and wave height, 1800h 10 Nov 1975. The “×” is the location of the Fitzgerald.

13. At 3:15 pm the Fitzgerald rounded Caribou Island and as Capt. Cooper later stated “[the Fitzgerald] was much closer to Six Fathom Shoal than I would want to be” (cf. note 19). Fifteen minutes later McSorley, via radiophone, contacted the Anderson:

“Anderson, this is the Fitzgerald. I have sustained some topside damage. I have a fence rail laid down, two vents lost or damaged, and a list. I’m checking down [reducing speed to allow the slower Anderson to catch up]. Will you stay by me til I get to Whitefish?”

“Charlie on that Fitzgerald. Do you have your pumps going?”

“Yes, both of them.”

At 4:10 pm McSorley radioed the Anderson again:

“Anderson, this is the Fitzgerald. I have lost both radars. Can you provide me with radar plots till we reach Whitefish Bay?”

“Charlie on that, Fitzgerald. We'll keep you advised of position.”

McSorley desperately attempted to locate the Whitefish Bay radio beacon and was advised by Capt. Cedric Woodard of the saltwater vessel Avafors that both the light and beacon were out of operation. For all practical purposes the Fitzgerald was now sailing completely blind in difficult seas. Around 5:50 pm Woodard radioed McSorley:

“Fitzgerald, this is the Avafors. I have the Whitefish light now but still am receiving no beacon. Over.”

“I’m very glad to hear it.”

“The wind is really howling down here. What are the conditions where you are?”

[Unintelligible shouts] “Don’t let nobody on deck!"

“What’s that, Fitzgerald? Unclear. Over.”

“I have a bad list, lost both radars. And am taking heavy seas over the deck. One of the worst seas I’ve ever been in.”

“If I’m correct, you have two radars.”

“They’re both gone.”

14. At 6:30 pm Cooper reported that two successive 30–35 ft waves buried the aft cabins and came over the bridge deck of the Anderson. Whether these rogue waves hit the Fitzgerald will never be known, but around 7:10 pm the Anderson first mate Morgan Clark radioed the Fitzgerald about an upbound ship and McSorley made no mention of high waves:

“Fitzgerald, this is the Anderson. Have you checked down?"

“Yes we have."

“Fitzgerald, we are about ten miles behind you, and gaining about 1½ miles per hour. Fitzgerald, there is a target nineteen miles ahead of us. So the target would be nine miles on ahead of you.”

“Well, am I going to clear?”

“Yes. He is going to pass to the west of you.”

“Well, fine.”

“By the way, Fitzgerald, how are you making out with your problem?”

“We are holding our own.”

“Okay, fine. I’ll be talking to you later.”

15. The Anderson never talked to the Fitzgerald again. The sea return [reflected radar signals] had intermittently obscured the Fitzgerald, but sometime around 7:15 pm its signal didn’t reappear. Cooper, unable to reestablish any form of contact or spot the Fitzgerald’s running lights on the horizon, assumed the ship lost. No one will ever know exactly what happened to the Fitzgerald – that knowledge now rests at the bottom of Lake Superior – but Schumacher (see note 10) tries to imagine the final moments:

“Throughout the tortured final moments of the Edmund Fitzgerald, the middle of the ship continued to twist and break. Hatch covers blew out, scattering taconite everywhere. The running lights flickered and went out. The ship’s two lifeboats broke free and rose with other flotsam toward the surface. The Fitz finally broke apart, the torque in the middle of the ship twisting the stern until it was actually upside-down when it broke away from the rest of the ship and dropped to the lake bottom floor. The bow came to a halt. The little air remaining in the Fitzgerald escaped and bubbled upward. Inside the remains of the Edmund Fitzgerald, 29 men lay dead or dying, some from drowning, others from the explosion of the boilers. Within a matter of minutes one of the Great Lakes’ finest ore carriers, the pride of the American flag, had become a grave site and no one on the surface had any idea of its fate.”

Although Lightfoot wrote “At seven pm a main hatchway caved in; he said, ‘Fellas, it's been good t’know ya!’” there was no distress call and no lifeboat launched. Whatever happened must have been “rapid and catastrophic.” In 2010 he changed the lyric – to absolve the crew of any negligence (see note 19) – to “At seven pm it grew dark, it was then he said; ‘Fellas it’s been good to know ya!’”

16. The Anderson eventually arrived safely in Whitefish Bay and at 8:30 pm Cooper radioed the Coast Guard on the distress channel stating “I am very concerned about the welfare of the steamer Edmund Fitzgerald. I can see no lights and don’t have him on radar. I just hope he didn’t take a nose dive.” He received a reply around 9:00 pm:

“Anderson, this is Group Soo [the Ste. Saint Marie Coast Guard Station]. What is your present position?”

“We’re down here, about two miles off Parisienne Island right now...the wind is northwest forty to forty-five miles here in the bay.”

“Is it calming down at all, do you think?”

“In the bay it is, but I heard a couple of the salties talking up there, and they wish they hadn’t gone out.”

“Do you think there is any possibility and you could...ah...come about and go back there and do any searching?”

Despite seas that “were tremendously large,” the Anderson along with freighter William Clay Ford returned to the Lake. They were joined around 11:00 pm by a Coast Gaurd Grumman Albatross aircraft from the Traverse City Station and two hours later by a Sikorsky Seaguard helicopter fitted with a Night Sun searchlight. They spent all night searching for the Fitzgerald with lights and flares but only found flotsam, including the Fitzzgerald’s two empty lifeboats.

THE AFTERMATH

17. News of the sinking spread quickly and it was widely reported the next day: “Ore ship feared sunk in lake storm” (Cleveland Plain Dealer), “Giant Ore Vessel, 29-man crew lost in Lake Superior” (Grand Rapids Press), “Freighter Sinks: Crew of 29 is hunted in Lake Superior” (Detroit News) and “Superior Ore Vessel Lost: November Curse Hits Again” (Kalamazoo Gazette). Walter Cronkite even briefly mentioned it on the CBS Evening News.

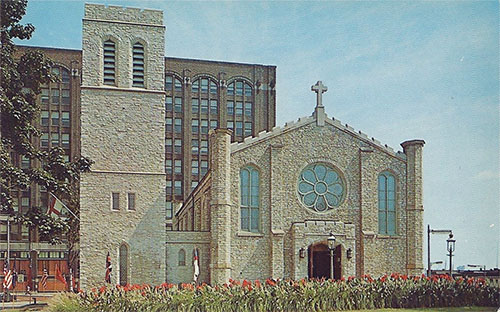

Hearing the news Bishop Richard W. Ingalls of the Anglican Mariners’ Church in Detroit held a silent prayer then rang the church bell 29 times – once for each member of the crew lost (see note 21). The remembrance was held every year until 2006. In 1985 Lightfoot attended the 10th anniversary service and after seeing the historic church changed his lyric from “In a musty old hall in Detroit they prayed in the Maritime Sailors’ Cathedral” to “In a rustic old hall...”

Postcard, Mariners’ Church, ca.1962

18. On the morning of 11 Nov a coordinated US-Canadian air/sea search was begun but was called off in the evening of the 13th after failing to find any trace of the ship or the crew. The next day, 14 Nov, a US Navy aircraft equipped with a magnetic anomaly detector (typically used to locate submarines) searched the area and found a strong signal in Canadian waters at 46° 59.9' N, 85° 06.6' W, some 17 miles from Whitefish Bay. The Coast Guard cutter Woodrush then followed up with side-scan sonar and found two large objects on the lake floor under 530 ft of water – presumably the wreck of the Fitzgerald.

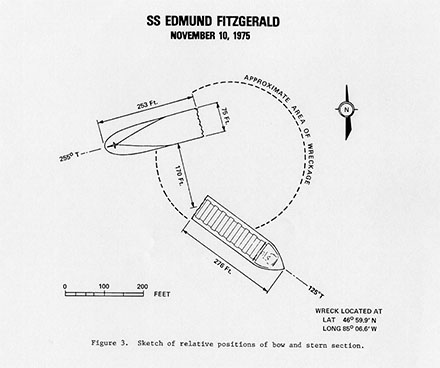

Six months later, between 20–28 May 1976, the Woodrush, carrying a borrowed Navy CURV-III submersible, positively indentified the wreckage of the Fitzgerald. They found the bow section upright on the lake bed and the stern section, separated by a 170-ft debris field, face down at a 50° angle:

From the NTSB report, ref. 19

19. The official inquiries began almost immediately and after a year of testimony the Coast Guard issued their report. They concluded that:

“The most probable cause of the sinking of the SS Edmund Fitzgerald was the loss a buoyancy and stability which resulted from massive flooding of the cargo hold. The flooding of the cargo hold took place through ineffective hatch closures as boarding seas rolled along the spar deck.”

The National Transportation Safety Board released their report in May 1978 and came to a similar conclusion:

“the probable cause of this accident was the sudden massive flooding of the cargo hold due to the collapse of one or more hatch covers. Before the hatch covers collapsed, flooding into the ballast tanks and tunnel through topside damage and flooding into the cargo hold through nonweathertight hatch covers caused a reduction of freeboard [the deck height above the waterline] and a list.”

See: Marine Casualty Report: SS Edmund Fitzgerald; Sinking in Lake Superior on November 10, 1975 with Loss of Life. Washington: Department of Transportation, US Coast Guard, 26 Jul 1977 (online), or for a summary: "The Sinking of the Edmund Fitzgerald" Proceedings of the Marine Safety Council. 1977 Dec 34(9–12), 160–172 (online) or Marine Accident Report: SS Edmund Fitzgerald Sinking in Lake Superior. Washington: National Transportation Safety Board, 4 May 1978 (online).

To many this conclusion wasn’t suprising. The maritime historian Frederick Stonehouse wrote that the typical Great Lakes ore carrier is the most commercially efficient vessel but also the least safe; without watertight bulkheads a puncture in the cargo hold as small as an inch could sink it. He called them “motorized barges.” See: Stonehouse, Frederick. The Wreck of the Edmund Fitzgerald. Au Train, Mich.: The Studios, 1982 (WorldCat).

Nevertheless the USGS/NTSB conclusions, which effectively absolved the carrier and blamed the hatch design and crew, were disputed by the families, the Lake Carriers’ Association and many seasoned Great Lakes mariners. As Capt. Brandon Durant of the Michipicoten stated: “You don’t head into any storm without even sending people around to re-dog the hatches.” Capt. Cooper, as close to an eyewitness as there was, testified that the ship sunk due to shoaling:

“I am positive he went over that six fathom bank! I know damn well he was in on that 36-foot spot, and if he was in there, he must have taken some hell of a seas. I swear he went in there. in fact, we were talking about it. we were concerned that he was in too close, that he was going to hit that shoal off Caribou, I mean, god, he was about three miles off the land beacon.”

Other theories included the ship breaking up on the surface due to successive rouge waves (the “Three Sisters”) or from stress-fractures in a poorly designed hull. See: “The Edumund Fitzgerald” Dive Detectives. Dir. Victor Kushmaniuk. Yap Films, 2009 (preview), or Kery, Shawn. A Forensic Investigation of The Breakup and Sinking of the Great Lakes Iron Ore Carrier Edmund Fitzgerald. Falls Church, VA: CSC Papers, 2013 (online).

Whatever the cause of the sinking Lightfoot’s lyric “They might have split up or they might have capsized; they may have broke deep and took water” pretty much covers all of the possibilities.

20. Over the years there have been a number of submersible expeditions to the wreck site, including Jean Michal Cousteau aboard the Calypso in Sep 1980 and Frederick Shannon’s “DeepQuest” Expedition in Jul 1994. None of these expeditions, however, offered any conclusive evidence to why the Fitzgerald sunk.

By this time the families of the Fitzgerald’s crew were becoming concerned about the increasing number of expeditions, and perhaps even more importantly, by advances in scuba gear that would allow divers access to the wreck. They considered the wreck a grave site and asked that a single artifact – the ship’s 200-lb bronze bell – be recovered to serve as a memorial. In a Canadian Navy/Great Lakes Shipwreck Museum joint expedition, sponsored in part by the Chippewa Nation, the bell was recovered on 4 Jul 1995. See: “Shipwreck: The Mystery of the Edmund Fitzgerald.” Dir. Christopher Rowley. Cinenova Productions, 1995 (YouTube).

The restored bell at the Great Lakes Shipwreck Museum

The families were determined not to allow the Fitzgerald site to become desecrated like the Titanic, Lusitania or Andrea Doria sites and petitioned the government of Ontario for help. In 2006 an amendment to the Ontario Heritage Act classified the Fitzgerald as a protected marine archeological site and dives, expeditions, even side-scan sonar is now prohibited.

APPENDIX

21. The crew list:

Ernest M. McSorley, Captain, 63 (29 Sep 1912 – 10 Nov 1975), Toledo, Ohio. McSorley began his career at age 18 aboard a saltwater vessel. He soon moved to Lake carriers and received his Master and First Class Pilot license (#398 598) and became captain of the Carrollton at the age of 38 – the youngest captain on the Great Lakes. He was the master of nine ships, most recently the Armco, before becoming the fourth captain of the Fitzgerald in 1972. “The sea was his life,” his stepdaughter said. Survived by his wife Nellie and three stepchildren.

John (Jack) H. McCarthy, First mate, 62 (14 Jul 1913 – 10 Nov 1975), Bay Village, OH. McCarthy began his career as a deckhand on the Yosemite and eventually earned his masters license. After shoaling the Ben E. Tate in 1956 his license was revoked but he ultimately regained it, serving as first mate on the Sylvania. He was McSorley’s first mate since 1970. Survived by his wife Mary Catherine and four children.

James A. Pratt, Second mate, 44 (29 Jan 1931 – 10 Nov 1975), Lakewood, OH. Survived by his wife and family.

Michael E. Armagost, Third mate, 37 (14 Oct 1938 – 10 Nov 1975), Iron River, WI. Survived by his wife Janice and two children.

George J. Holl, Chief engineer, 60 (11 Mar 1915 – 10 Nov 1975), Cabot, PA. Survived by his brother Wilmer.

Edward F. Bindon, First assistant engineer, 47 (7 Jan 1928 – 10 Nov 1975), Fairport Harbor, OH. Survived by his wife Helen.

Thomas E. Edwards, Second assistant engineer, 50 (28 Feb 1925 – 10 Nov 1975), Oregon, OH. Survived by his wife and family.

Russell G. Haskell, Second assistant engineer, 40 (19 May 1935 – 10 Nov 1975), Millbury, OH. Survived by his wife and family.

Oliver (Buck) J. Champeau, Third assistent engineer, 41 (4 Sep 1934 – 10 Nov 1975), Milwaukee, WI. Champeau quit school to support his mother, served in the Marines during the Korean War and began working on boats in 1961. He had been in the Fitzgerald’s engine room for three years. Survived by his daughter Deborah.

Frederick J. Beetcher, Porter, 56 (24 Feb 1919 – 10 Nov 1975), Superior, WI. Survived by his son Gene.

Thomas Bentsen, Oiler, 23 (10 Jan 1952 – 10 Nov 1975), St, Joseph, MI. Survived by his parents.

Thomas D. Borgeson, AB maintenance man, 41 (26 Nov 1934 – 10 Nov 1975), Duluth, MN. Survived by his three children.

Nolan F. Church, Porter, 55 (13 Jul 1920 – 10 Nov 1975), Silver Bay, MN. Church began his career on the Great Lakes well into his 40s and served on several freighters before the Fitzgerald. Survived by his wife and three daughters.

Ranson E. Cundy, Watchman, 53 (16 Apr 1922 – 10 Nov 1975), Superior, WI. Cundy began his career on the Great Lakes after his service in the Marines in WWII. He had been on the Fitzgerald for nearly eight years. Survived by his daughter Cheryl.

Bruce L. Hudson, Deckhand, 22 (10 Sep 1953 – 10 Nov 1975), North Olmstead, OH. Survived by his parents.

Allen G. Kalman, Second cook, 43 (7 Deb 1932 – 10 Nov 1975), Washburn, WI. Survived by his wife and five children.

Gordon F. MacLellan, Wiper, 30 (2 Aug 1945 – 10 Nov 1975), Clearwater, FL. MacLellan followed the footsteps of his father who was a Great Lakes master. He had served on the Fitzgerald for five years. Survived by his parents.

Joseph W. Mazes, Special maintenance man, 59 (13 Feb 1916 – 10 Nov 1975), Ashland, WI. Survived by his three siblings.

Eugene W. O’Brien, Wheelsman, 50 (17 Jul 1925 – 10 Nov 1975), St. Paul, MI. O’Brien first started as a deckhand at the age of 16 and had worked on the Fitzgerald more than once in his career. He had the 4–8 pm shift and was likely in the pilothouse when the Fitzgerald sunk. Survived by his son John.

Carl A. Peckol, Watchman, 20 (6 Sep 1955 – 10 Nov 1975), St. Paul, MI. Survived by his parents.

John A. Poviach, Wheelsman, 59 (6 Jun 1916 – 10 Nov 1975), Bradenton, FL. Survived by his wife Mary and two daughters.

Robert C. Rafferty, Steward, 62 (Jun 1313 – 10 Nov 1975), Toledo, OH. Rafferty was not originally scheduled to be on the Fitzgerald but was filing in for Richard Bishop who was home sick with bleeding ulcers. Survived by his wife Brooksie and daughter Pam.

Paul M. Riippa, Deckhand, 22 (15 Aug 1953 – 10 Nov 1975), Ashtabula, OH. Survived by his mother.

John D. Simmons, Wheelsman, 63 (25 Aug 1913 – 10 Nov 1975), Ashland, WI. Simmons was the senior wheelsman aboard the Fitzgerald and it was reportedly his last trip before retirement. Survived by his wife Florence and daughter Mary.

Willian J. Spengler, Watchman, 59 (11 Sep 1916 – 10 Nov 1975), Toledo, OH. Survived by his wife and family.

Mark A. Thomas, Deckhand, 21 (14 Aug 1954 – 10 Nov 1975), Richmond Heights, OH. Survived by his father.

Ralph G. Walton, Oiler, 58 (22 Jul 1917 – 10 Nov 1975), Fremont, OH. Survived by his wife and son Alan

David E. Weiss, Cadet, 22 (13 Nov 1953 – 10 Nov 1975), Agoura, CA. Weiss was a Maritime Academy cadet and was assigned to the Fitzgerald. Supposedly he was going to swap his assignment with cadet Dean Hobbs aboard the Amoco Indiana when the ships passed through the Soo Locks. Survived by his parents

Blaine H. Wilhelm, Oiler, 52 (12 Aug 1923 – 10 Nov 1975), Moquah, WI. Wilhelm began working on Great Lake freighters after an 11-year career in the Navy. Survived by his wife Lorraine and seven children.

11 Aug 2015, updated 19 Aug 2015 ‧ Unclassified