Detail, ASL Beyond Valor countersheet 8225025/26

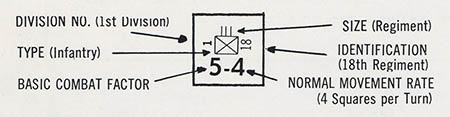

The Counter

Charles Roberts, Redmond Simonsen and Information Design

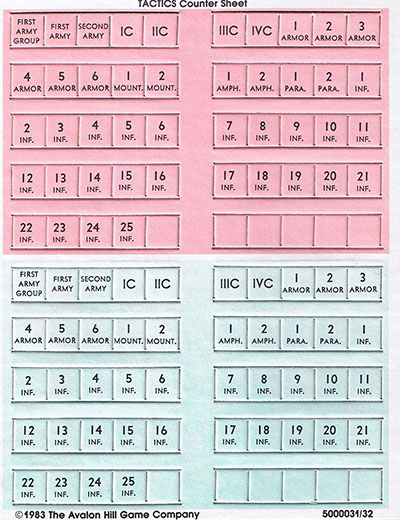

When Charles S. Roberts (3 Feb 1930 – 20 Aug 2010) began selling his wargame Tactics from his apartment in Avalon, Maryland in 1954 he, out of financial necessity, replaced the traditional wood, plastic or metal game piece with something he could afford to manufacture – a printed sheet of die-cut cardboard squares. These cardboard squares would be known by several generations of wargamers as the counter. The original ½" square Tactics counters included two pieces of information: the unit type and an identifying serial number:

Tactics 25th Anniversary countersheet, 1983

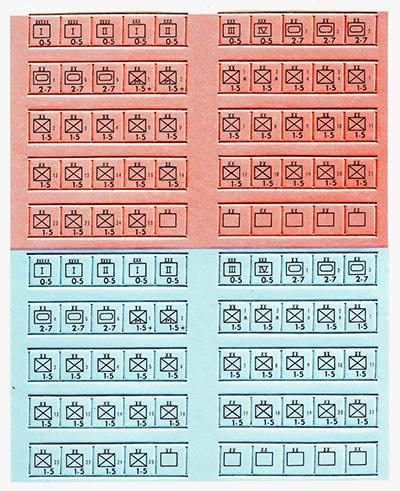

Roberts redesigned the game and released Tactics II in 1958. He updated the counters to include standard US military map symbols to identify unit types as well as values for combat strength and movement – a total of five pieces of information.1

Tactics II countersheet, 1958

Although you can argue that military symbols were somewhat inscrutable to anyone other than the armchair historian, that was exactly who Roberts was marketing the game to. For this crowd the symbols lent a certain verisimilitude, with the game board and pieces simulating a “live” military situation map during play. It turned out to be an inspired design choice.

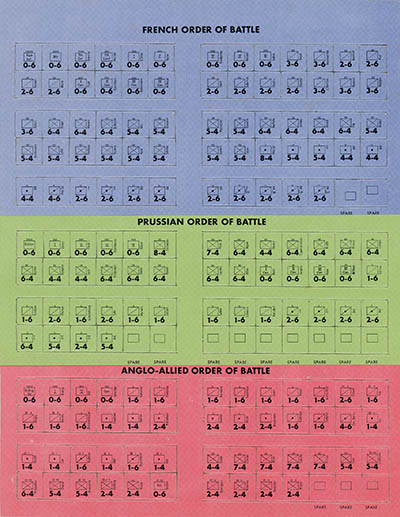

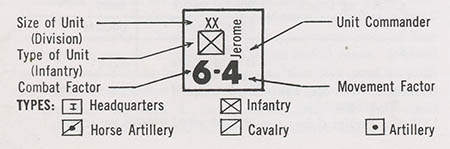

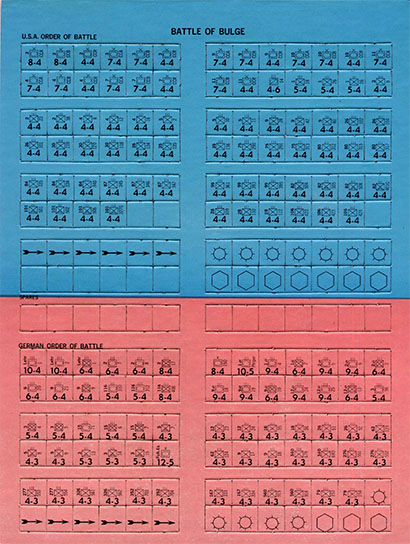

In 1963 Roberts was forced to turn over his game company to his major creditor – the printer Monarch Services.2 Nevertheless the newly re-structured Avalon Hill used Roberts’ counter design almost exclusively for the rest of the decade. Here, for example, are the counters from the 1962 Waterloo and the 1965 Battle of the Bulge, which add only two more pieces of historical data to the counter:

Waterloo countersheet, 1962

Battle of the Bulge countersheet, 1965

By the end of the 1960s the wargame hobby was taking off and the games shifted from a strategic scale to a more granular and complex tactical scale. The next breakthrough in game design was Jim Dunnigan’s tactical armor game Panzerblitz.

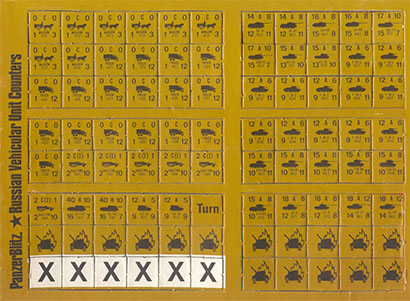

In 1969 Jim Dunnigan, former missile repairman, accountant, historian and game designer purchased the military history/wargame magazine Strategy and Tactics. His first hire was the Cooper Union trained graphic designer Redmod A. Simonsen (8 Jun 1942 – 8 Mar 2005). For the next 14 years they featured a complete game in nearly every issue of the magazine. In the summer of 1969 S&T featured Dunnigan’s platoon/company level Tactical Game 3, which was bought by Avalon Hill and developed into PanzerBlitz.3

Simonsen considered the design of games as deeply and as essentially as anyone ever. In a process he termed “physical system design” he considered the interrelationship of every facet of the game: the rule system, the playing aids, the game board and the counters. To him proper design wasn’t just art direction but a process where the information on the game components were reduced to the absolute essentials – “the more complex the game system, the less decorated it should be,” he said. In regards to counters he wrote:

“...what is the information load of the counter and is it appropriate to the game system? Traditionally, the designer attempts to put as much useful information as possible on the counter face. It may be possible, however, to eliminate some information as redundant. It may also be possible – and desirable in specific games – to pull the information from the counter and place it on a data sheet separate from the playing pieces.” 4

For the ⅝" PanzerBlitz counters Simonsen included offensive and defensive values, range and movement values, an ID and name and finally, as a nod to miniture gaming, a recognizable silhouette – a total of seven pieces of information. It was an elegant solution to the increasing amount of information necessary to the play the modern wargame. His work on Panzerblitz stands as a high point in the history of game design.

PanzerBlitz, Russian Vehicular countersheet, 1970

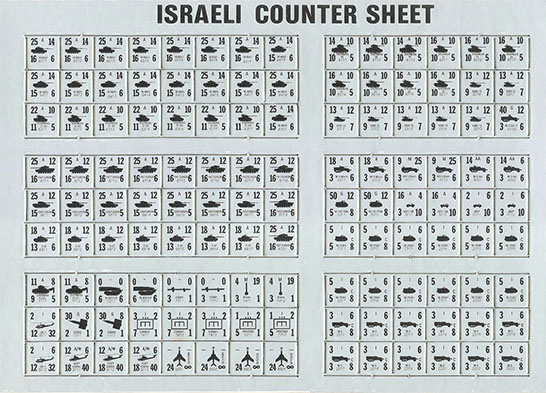

Arab-Israeli Wars, Israeli countersheet, 1977

The PanzerBlitz system spawned several sequels and was the dominant game system until John Hill’s Squad Leader was published in 1977.5 Hill (21 Feb 1945 – 12 Jan 2015), a civil war miniaturist and one-time game store owner, based Squad Leader on his love of miniatures and introduced a level of detail previously unseen in a boardgame.

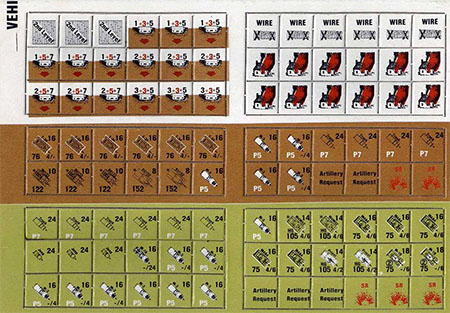

The ⅝" counters, prepared by Roger MacGowan, represented a single vehicle or piece of ordinance and included values for the weaponry, movement, a name and a top down silhouette. A second level of information was presented with typographic conventions (circles, boxes, asterisks, etc.) and yet another level was presented with color. In all, as many as a dozen pieces of information:

Detail, Squad Leader Vehicles and Fortifications countersheet, 1978

Squad Leader turned out to be so popular that a series of expansions (or gamettes) were published. Each gamette presented new rules, obsoleting previous rules and in many cases the previous counters. The end result was – to be kind – something of a hot mess. Realizing this, Avalon Hill decided to completely scrap the system and start over. The idea was to condense, simplify and clarify the byzantine rule system. But that’s not exactly how things turned out.

Edward Tufte famously wrote “to clarify, add detail” and the designer Don Greenwood apparently took this to heart with Advanced Squad Leader. When released in 1985 it included a 150+ page read-the-entire-thing-before-you-can-play rule book. To the wargame community it was either charmingly complex or too complex to be charming. Greenwood even conceded this point in the introduction, writing “ASL is still a bit much for the uninitiated.”

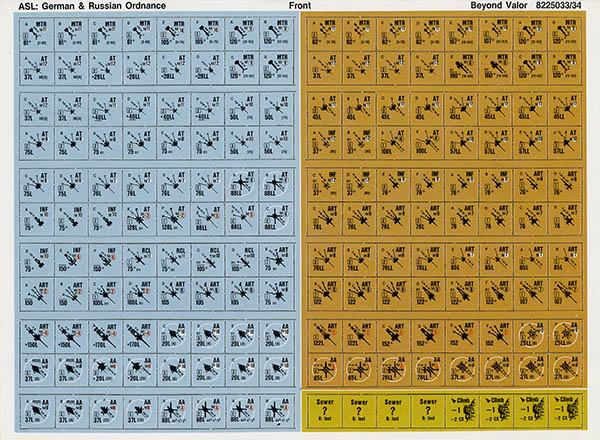

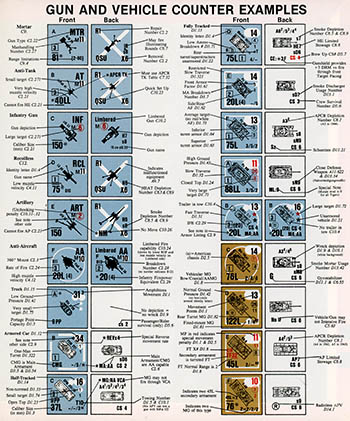

The new ASL counters, prepared by Charles Kibler, included an extraordinary amount of esoteric information: everything from vehicle ground pressure to target size to turret armor thickness to the presence of gyrostabilizers, radios and bizarre one-off German weapon systems. It was so much information that it took the entire back cover of the rulebook to show just the basics:

ASL Beyond Valor countersheets, 1985

Back cover, ASL rulebook, 1985

ASL represented the last great attempt at a tactical-level game system before the rise of computer simulations. The counters included as much as 10× more information than Robert’s Tactics counters 30 years earlier and are pretty much at the outer envelope for how much data could be put on a cardboard square and still be playable (and to some that last point is debatable). These playability issues aside, Greenwood, et. al. managed to abstract, model and differentiate nearly every weapon used anywhere in the world from the early 1930s to the late 1940s on a ½ or ⅝" counter. They are a classic of not only game design but of information design.

1. Robert’s symbols were likely based on the WWII field manual FM 21-30 Conventional Signs, Military Symbols and Abbreviations 1941-11-26. (online). For more on military mapping vis-a-vis game design see: Hershey, Andrew. “Not Just Lines on a Map: A History of Military Mapping.” Strategy & Tactics 274: May–June 2012, 23 (online).

2. Monarch Services began as a Baltimore envelope/direct mail circular printer. After they acquired Roberts’ game company their focus shifted to strategic wargames. Realizing that their fortunes were now tied to adolescent boys they diversified into magazines, publishing the tween title Girls Life. Strange bedfellows, indeed.

3. See: Arvold, Alan. “An Informal History of the Development of PanzerBlitz. Imaginative Strategist, 2009 (online).

4. See: Emrich, Alan and MacGowan, Roger. “Our View is Better Because We Stood on the Shoulders of a Giant: Redmond A. Simonsen.” (online).

5. True story: Your humble narrator bought this game, sight unseen, via mail-order in 1977 when it was first announced by Avalon Hill. When it finally arrived I was so engrossed that, lets just say I failed a few grade school science tests. Eventually my parents confiscated the game and it lived in their bedroom closet for several months. By the time I gave up the game for girls the counters had been worn down to a koan-like smoothness. File this note under “the wistful memories of childhood.”

23 Jun 2015, updated 6 Aug 2015 ‧ Design