Betsy, Christina, Siri and Helga

Andrew Wyeth

On Andrew Wyeth’s 22nd birthday he ventured to Cushing, Maine to meet the artist Merle James but instead met James’ 17-year old daughter Betsy. Instantly smitten, he asked her to show him around town and she was more than happy to oblige. She thought “I’ll show him a real Maine building” and as something of a test took him to the Hathorne Point home of her friends Christina and Alvaro Olson.1

Throughout his life Andrew had a rather contentious relationship with women; indeed with anyone who didn’t in some way directly support his painting, but on that day in July 1939 he met what would become two of the most important women in his life.1

Like Andrew, Betsy had health problems as a child and grew up a loner. “I was the flawed child” she said. They married in May 1940 and she was initially dismissed by Andrew’s domineering father, N. C., as a lightweight dillitente. She would prove N. C. and the rest of Wyeth’s family wrong, becoming not only Andrew’s wife and model but his staunchest supporter and most severe critic, his business manager and eventually his archivist.

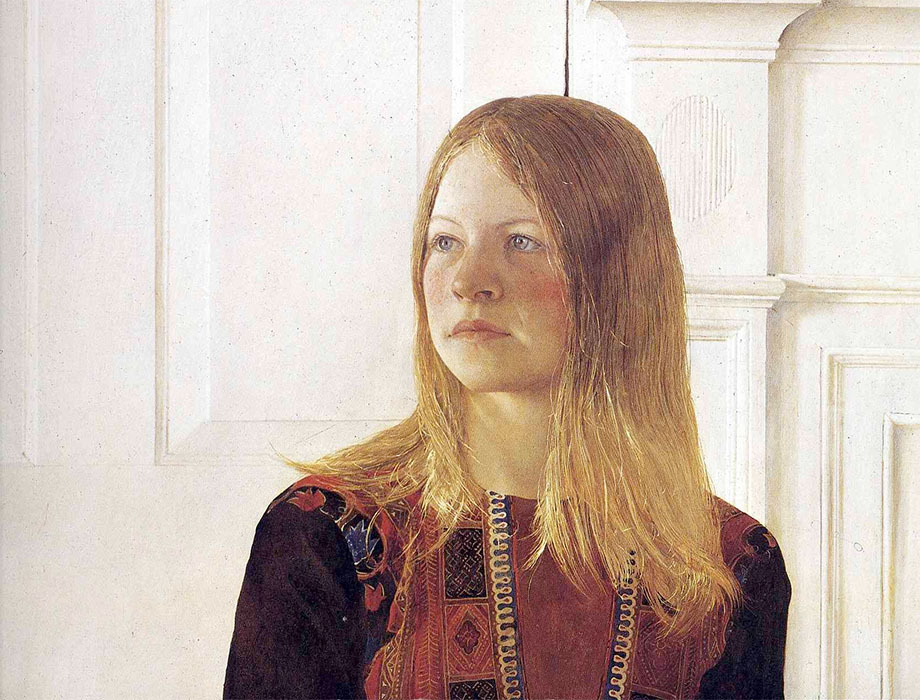

Sandspit, 1953

Maga’s Daughter, 1966

Betsy knew that the Olsen’s were difficult, reclusive people. Andrew, however, was completely unfazed by their dilapidated house and as he later recalled “Owing to Christina’s real fondness for Betsy, she accepted me much more readily than I suppose she ordinarily would have.”

By this time Christina, who had an undiagnosed neuromuscular disease (likely polio) was reduced to crawling and urinating on stacks of discarded newspapers. Andrew however felt that “she was so much bigger than all the little idiosyncrasies.” and found her a symbol of fierce independance - an extraordinary conquest of life. The result of this friendship was Christina’s World, one of the iconic paintings of the 20th century.

Andrew and Betsy spent their winters in Chadds Ford, Pennsylvania and their summers in Cushing where he routinely returned to the Olsons and their saltwater farm as a subject. He eventually had free run of their house, even setting up his studio in an upstairs bedroom.

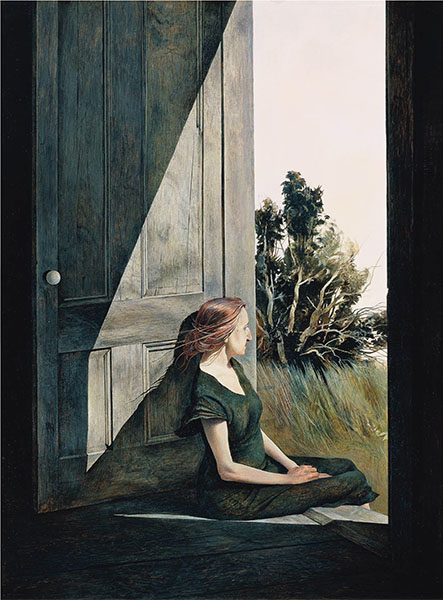

Christina Olsen, 1947

Christina’s World, 1948

Anna Christina Olsen, 1967

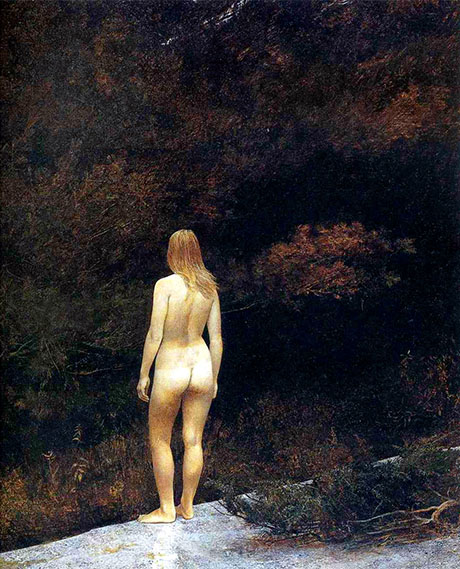

Christina’s death in Jan 1968 deeply affected Andrew and marked the end of a seminal two decade long period in his painting. Faced with a blank canvas – as it were – it was time for a reappraisal of his art. It was then that he met Siri, the daughter of the Cushing farmer George Erickson. Siri was exotic, untouched and had an electrifying effect on his work. “A burst of life,” he later said, “like spring coming through the ground, a rebirth of something fresh out of death.”

It was Betsy (much to her later chagrin) who pushed him to do nudes. Because his model was only 14 years old it became – as you could imagine – something of a scandal.

The Sauna, 1969

Indian Summer, 1970

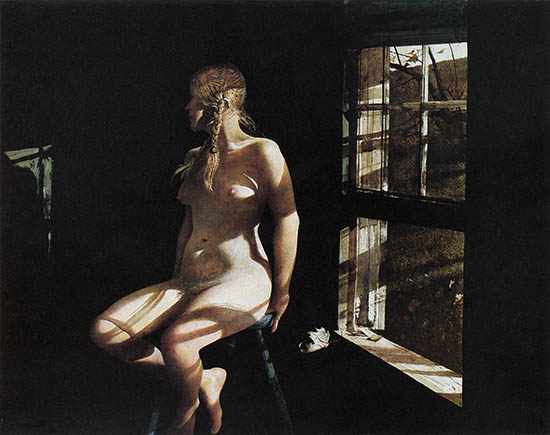

Wyeth painted Siri for ten years, until Betsy – worried that their relationship had turned sexual – put a stop to it. She told Andrew “If you do this again, don’t tell me.” Her request would have rather far-reaching consequences because Andrew had just met Helga.

Helga was born in Konigsberg, Prussia in 1939. After surviving the war her family was held as prisoners in Denmark. At age 16 she entered the convent but left a few years later and met John Testorf. They married, moved to Philadelphia and finally settled in Chadds Ford. By the time she met Andrew she was a lonely, unhappy, homesick housewife and posing for Andrew was her answer. “I became alive,” she said, “It shows in the pictures. I became young overnight. I’ve never done anything more worthwhile.”

Letting Her Hair Down, 1972 (from ref. 2)

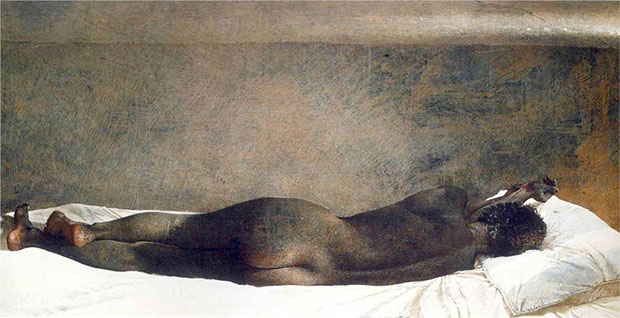

Wyeth spent the next 15 years painting Helga in near complete secrecy. To hide her from Betsy he shuttled her from studio to studio (“like a hamster in a cage”) and began finding excuses to remain in Chadds Ford while Betsy was in Maine. What few pieces he showed Betsy carefully concealed Helga’s identity. He even changed her skin color in Barracoon:

Barracoon, 1976

On Her Knees, 1977

Overflow, 1977

Lovers, 1981

Eventually he tired of the subterfuge and showed his work – some 240 pieces – to Betsy. Her first reaction was that “Whew, I was absolutely overcome,” and her next was “Who the fuck was this woman?” The Wyeths sold the entire collection to the publisher Leonard E. B. Andrews and in a masterful piece of public relations the story spread beyond art circles, with the salacious details of Wyeth’s secret model becoming the simultaneous cover story in both Time and Newsweek.

Wyeth’s artwork remains to this day a polarizing subject – either you love it or you hate it. It would be difficult, however, to deny his love of his models. As one of them stated “its a romance to to the degree where you’re the most important thing in the world to him.”

1. For a complete biography see: Meryman, Richard. Andrew Wyeth: A Secret Life. New York: HarperCollins, 1996 (WorldCat).

2. All of the Helga images are from Wilmerding, John. Andrew Wyeth: The Helga Pictures. New York: Harry Abrams, 1987 (WorldCat).

1 Dec 2013 ‧ Illustration