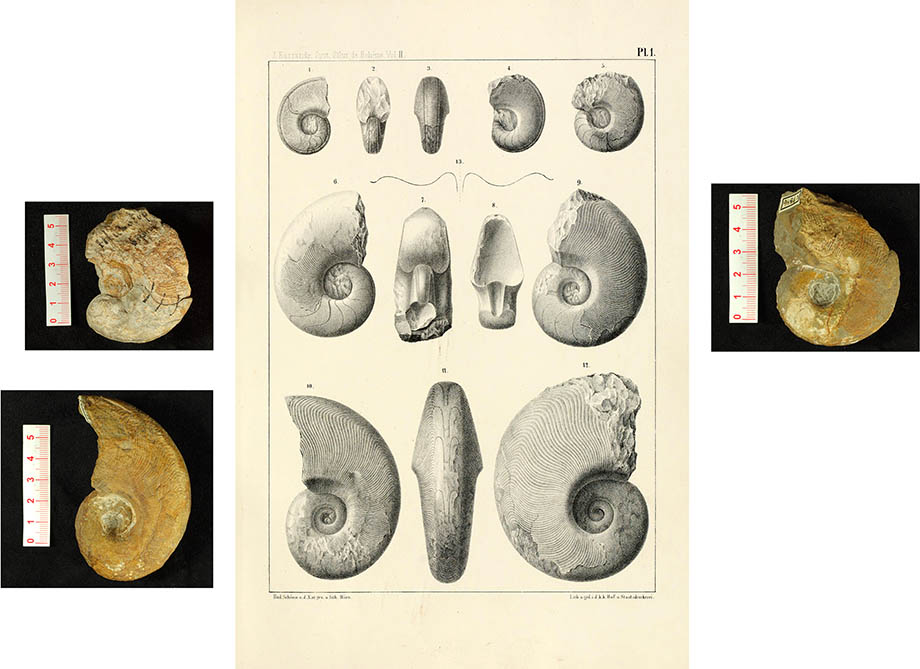

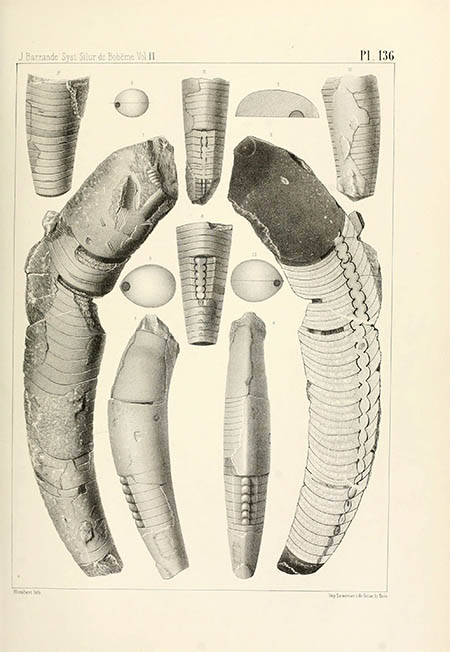

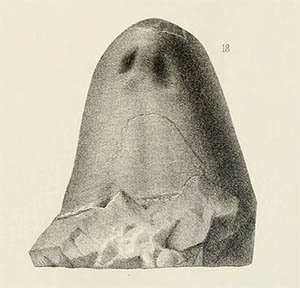

This lithograph of Goniatites bohemicus appeared in Joachim Barrande’s Systême Silurien du Centre de la Bohême.1 The artist, M. Humbert from Lemercier in Paris, prepared the Solnhofen lithographic limestone plate to Barrande’s exacting requirements using fossils from his extensive collection (as shown). It is one of more than a thousand similarly executed plates in the monumental Systême.

Joachim Barrande, the son of the shopkeeper Augustin Barrande and his wife Charlotte, was born on 11 Aug 1799 in Saugues, Haute Loire.2 He studied civil engineering at the École Polytechnique in Paris, graduated at the top of his class and in 1826 he came into the service of King Charles X as the science tutor of his grandson Henry, the Comte du Chambord. After Charles X was forced to abdicate in the July Revolution of 1830 Barrende followed the royal court to Dorset, Edinburgh and finally Prague.1

Charles X and his family eventually moved on to Trieste but Barrande stayed in Prague where he began work as a road and bridge engineer. Barrande had a keen interest in the natural sciences and the story goes that his interest in paleontology was piqued while observing fossils found during his surveying work on the planned Radnice-Plzeň-Budějovice railway. Whatever the reasons he started collecting fossils, however, it was the publication of Murchison’s Silurian System in 1839 that focused his interest.3 He realized that his finds were the same ones that Murchison was describing and soon he began a much more systematic study.

Goniatites bohemicus

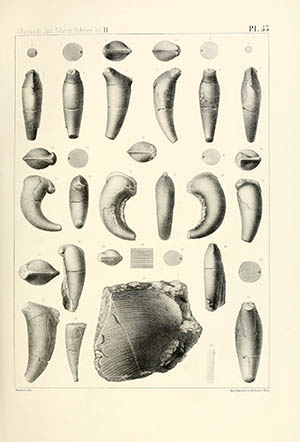

Phragmoceras sp. (left), Trochoceras and Gyroceras sp. (right)

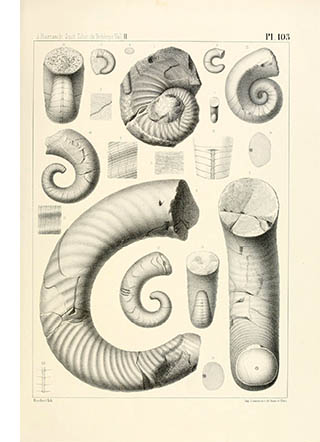

Cyrtoceras sp.

Between 1840–50 Barrande travelled on foot through the mountains between Prague and Beroun and created a stratigraphic map of Central Bohemia. He identified Paleozoic rock formations and hired workers – as many as 20 or 30 at a time – to dig for fossils. He was so successful in finding fossil beds that his laborers “attributed to him a mastery of the black art of divination and a possible intimacy with the devil himself.” By the time he died he had amassed a collection of more than 100,000 specimens.

He began organizing his notes and in 1852, under the fitting motto of “C’est ce que j’ai vu” (this is what I have observed), published the first folio of his remarkable Systême Silurien du Centre de la Bohême.

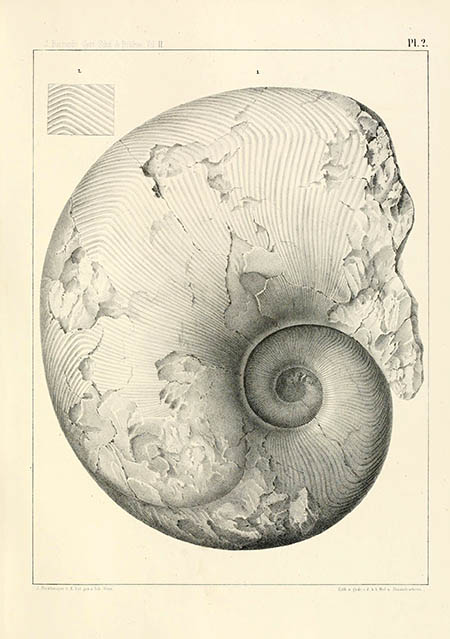

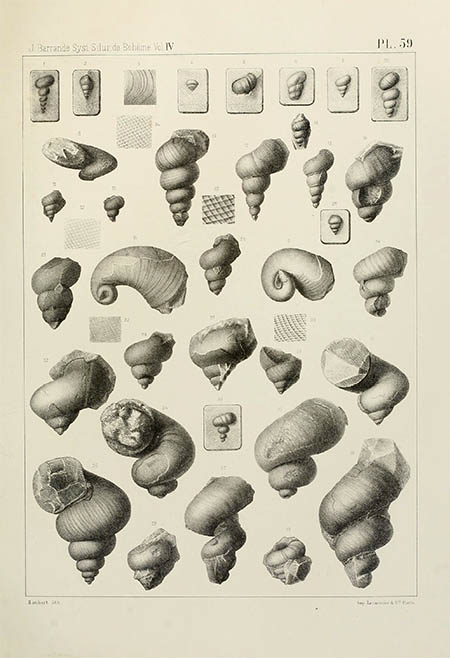

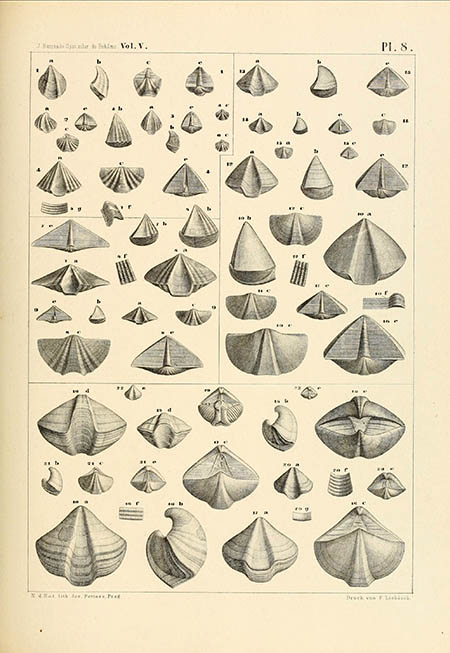

Over the next 31 years – until his death in 1883 – he published 22 quarto folios covering trilobites, cephalopods, pteropods, brachiopods and molluscs. In all the Systême included 6887 pages of text, 1078 plates and described 3560 Lower Palaeozoic species. It was a monumental work that simply has no parallel in the history of palentology.

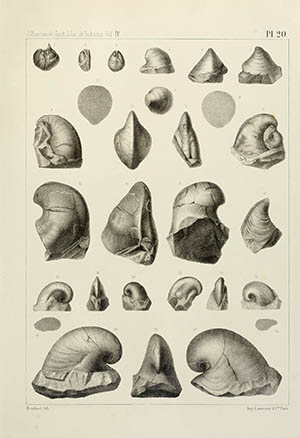

Monomercella and Orthonychia sp. (left), Herecynella bohemica and Philhedra humillima (right)

Loxonema sp.

Barrande found it necessary to act as his own publisher and set up his own press in Prague. There was no part of the project that escaped his obsessive supervision – especially the plates. He personally designed and laid out the illustrations and left extensive instructions to his artists including J. Fetters (Prague), A. Swoboda (Vienna) and M. Humbert (Paris). He routinely demanded revisions and even discarded perfectly usable plates at the last minute when a better specimen became available. As Science noted in their 1888 obituary “[they] could not have been printed with greater technical elegance by any press in Paris.”4

Of course Barrande’s obsessiveness was expensive. The project required continual financial support from the Academy of Science in Vienna and the Comte du Chambord. Even with a prohibitive price of 1575 francs the publication never broke even.

Certina and Spirifa sp.

Barrande’s publication would turn out to be critically important to Charles Darwin. He mentioned his work no less than five times in the Origin of the Species.5 Barrande, on the other hand, felt that his work was “to ascertain the reality, not to create ephemeral theories” and his idea of “colonies” would become one of the chief scientific alternatives to Darwin’s theory of evolution.

Barrande had amassed so much material that after his death in 1883 three volumes describing an additional 1000 species were published. Today, more than a century later, his work is still routinely referenced by paleontologists.

1. Barrande, Joachim. Systême Silurien du Centre de la Bohême (the Silurian System of Central Boehmia) (8 volumes). Prague: Chez l’auteur, 1852–1911. Volumes 2–8 are online. The missing volume, unfortunately, is the trilobite volume – hence no trilobite scans in the post. Sorry. If a version of volume 1 ever becomes available – trust me – I’ll be all over it.

2. For a more complete biography of Barrande see Radvan Horný, Radvan and Turek Vojtěch. Jaochim Barrande: His Life, Work and Heritage to World Palaeontology. Prague: Praha Národní Muzeum, Přírodovědecké Muzeum, 1999. (WorldCat, online), or Kříž, Jiří. Joachim Barrande. Prague: Český geologický ústav, 1999 (online)

3. Murchisen, Roderick. The Silurian System. London: John Murray, 1839 (online).

4. Joachim Barrande, His Life. Science. 30 Nov 1883; 2(43): 699–701 (online)

5. Darwin, Charles. On the Origin of the Species. London: John Murray, 1859 (WorldCat, online).

Orthonychia dorsata, AKA, fossilized Pac-man ghost

4 Jun 2014 ‧ Illustration