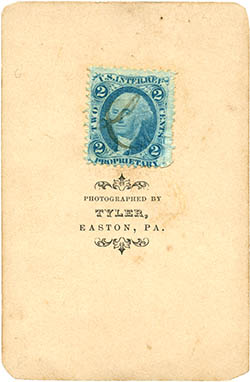

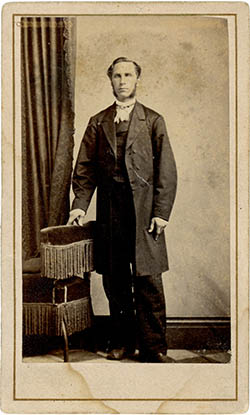

These carte-de-visites (or just cartes or CDVs) of a rather handsome young couple and presumably the young brides’ sisters were photographed by the Tyler studio, Easton, Pennsylvania. The hand-cancelled 2-cent revenue stamp date the photos to 1864– 1866.1 They are completely typical Civil War era CDVs.

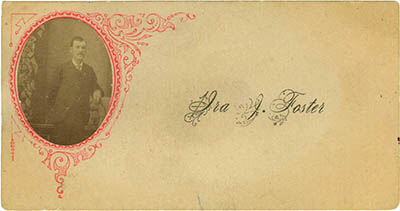

The carte-de-visite, or calling card, has its roots in French social custom. The cards were presented by visitors and, often, saved by the recipients in albums. Originally the cards displayed a simple engraved or calligraphic name but over time they became more decorative and complex. Eventually the more well-heeled began to include a gem-sized (½ × 1") photograph on their cards:

French calling card

Calling card with gem-sized photo. ca.1860s

So by the mid-19th century it it wasn’t much of a jump to include a full-size albumin print on the card. Exactly who though of this first is unknown, perhaps Louis Dodero or E. Delessert, but the credit would go to André Disdéri.

André Adolphe Eugène Disdéri (28 Mar 1819 – 4 Oct 1889) started as a daguerreian in Brest in 1848 and by 1852 had a studio in Paris. On 27 Nov 1854, he applied for a patent for a process where eight 6 × 9 cm images could be shot on a single full size wet plate:2

Clara Silvois, Andre Disdéri. 1862. Metropolitan Museum of Art

Napoleon III and Empress Eugenie, Andre Disdéri. 1865. Metropolitan Museum of Art

Disdéri’s process, obviously, greatly reduced cost and soon the popularity of the CDV spread; first throughout France, then England (1857) and America (1860). Their popularity made Disdéri a rather wealthy and renowned photographer and at one point he had studios in Paris, Toulon, Madrid and London.3

Second Empire and Victorian families would collect CDVs of friends and family and, after John Mayall mass-produced images of Queen Victoria and the royal family in 1860, images of famous persons and celebrities. Collecting cards became so popular, both in Europe and America, that the term “cardomania” was coined to describe it. As Oliver Wendell Holmes wrote in 1863: “Card portraits, as everybody knows, have become the social currency, the ‘green-backs’ of civilization.”

The Royal Family. John Mayall, 1860

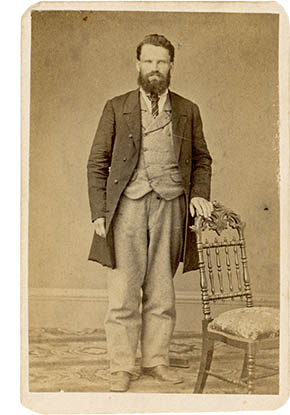

Here is a representative example of American CDVs taken between 1864–1866:

Oline M. Boomer of Mendota, IL

Hannah Cook of Washington, PA

1. As part of the Revenue Act of 1864 Congress passed a law adding a new tax on all “photographs, ambrotypes, daguerreotypes or any other sun-pictures,” This tax, to help fund the war, was in effect from 1 Aug 1864 – 1 Aug 1866. In addition to photographs, alcohol, tobacco, matches, perfume, Playing Cards, Bank Checks, Certificates, Bill of Lading, etc were taxed. Some of these revenue stamps have some philatelic value (although, sadly, not the ones shown here)

IYI, CDVs were taxed based on the cost of the photo: less than 25 cents: 2 cents tax (blue/orange stamp), 25 – 50 cents: 3 cents (green), 50 cents – $1: 5 cents (red). More than $1: 5 cents for each additional dollar or fraction of a dollar. The penalty for failing to charge tax was 10 USD, so compliance among photographers was rather high.

2. “Pour des perfectionnements en photographie, notamment appliqué aux cartes de visite, portraits, monuments, etc.” Disdéri is also credited with inventing the twin-lens reflex camera.

3. Of course, it never ends this way, does it? By the end of his life Disdéri was a penniless, nearly blind beach photographer in Nice.

12 Dec 2009, updated 21 Dec 2014 ‧ Photography