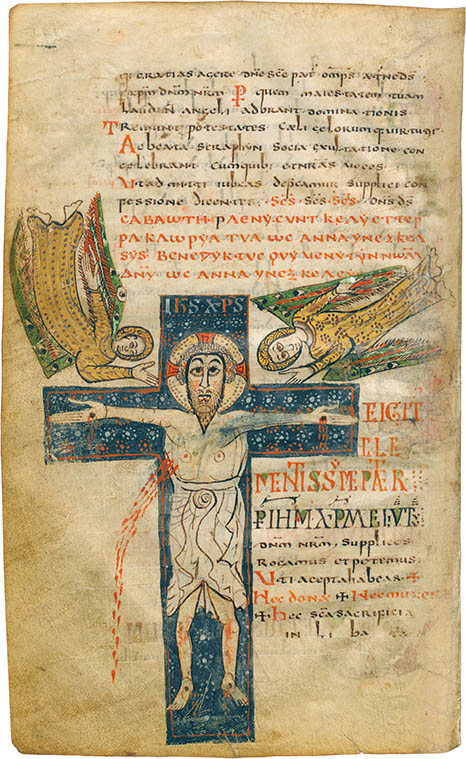

Folio 143, verso

50

Sacramentaire de Gellone

Carolingian Minuscule

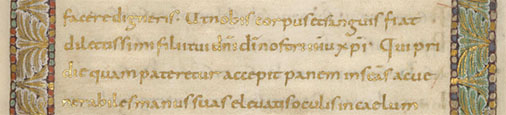

This classic leaf from the Sacramentaire de Gellone (Gellone Sacramentary) shows the crucified Christ attended by two angels. The angels are singing the sanctus (directly above the image in red) and the cross forms an elaborate historiated T, the beginning of Te igitur, the eucharistic prayer which asks for Jesus’ blessing of the offering. So the image integrates with the text and visually separates the prayers. A masterful design.

Although the origins of the manuscript are unclear, Deshusses suggests that it was written either at Meaux or Cambrai around 790 for Bishop Hildoard of Cambrai.1 The sacramentary ended up at Saint-Guilhem-le-Désert, near Lodève, perhaps as one of the gifts Louis the Pious and Duke William of Toulouse presented to the monastery shortly after it was founded by William of Gelone in 804. The manuscript is now held by the Bibliothèque nationale de France.2

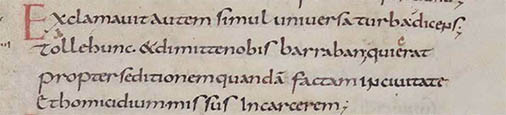

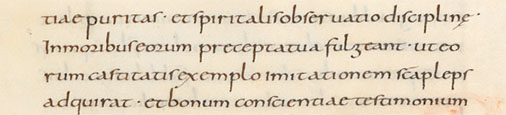

The text, of which 270 pages remain, presents most of the liturgy of the Merovingian church, a combination of Roman and Gallican rites – the so-called mixed Gelasian text. It just barely predates Charlemagne's reforms and the introduction of the Gregorian sacramentary. If you are so inclined there is plenty of literary and historical criticism,3 but for now lets just talk about the design.

The illuminations, miniatures and historiated initials represent a high point of late Merovingian book art and the script represents an excellent example of early Carolingian minuscule. It is, as Bischoff states: “A demonstration of what richness in initial forms and motifs a virtuoso and imaginatively inspired late-eighth-century miniaturist could employ...”4 Here are several more pages:

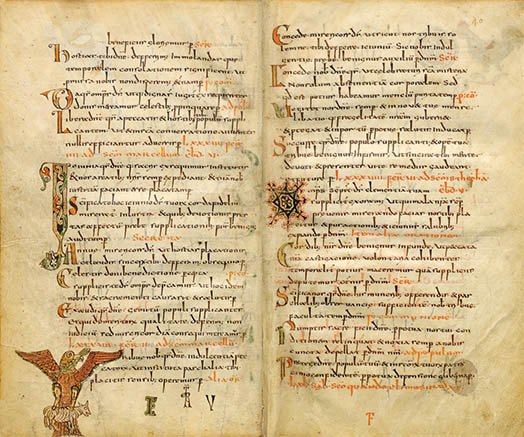

Folio 39, verso and 40, recto

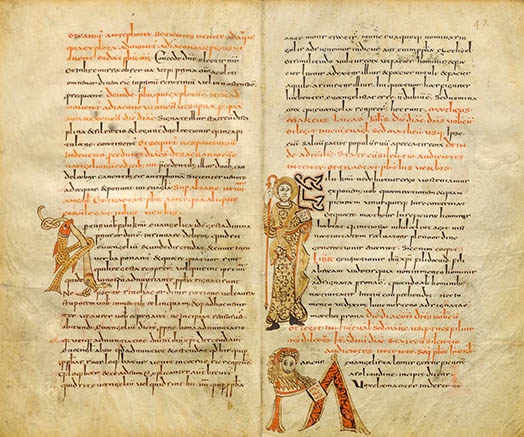

Folio 41, verso and 42, recto

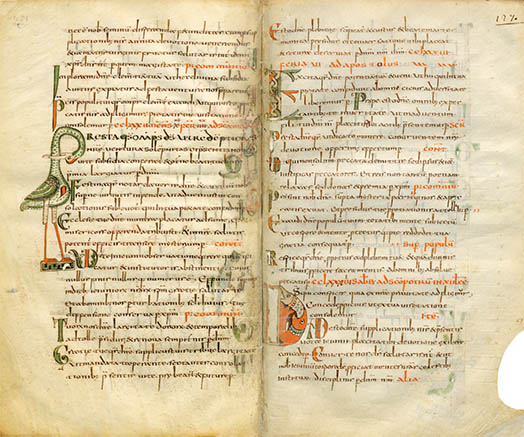

Folio 126, verso and 127, recto

The Roman scripts of the fourth century evolved over the next several hundred years into many different regional styles, e.g.: Roman cursive minuscule became Insular Majuscule in Ireland and England, or Merovingian and Luxeuil minuscules in France, or Lombardic and Beneventan minuscules in Southern Italy, or Visigothic minuscule in Spain, or Germanic minuscule in Germany, etc. The point is that by the eight century the situation was a mess5 and this, not surprisingly, proved rather problematic for Charlemagne’s administration of his Frankish empire.

To rectify this situation Charlemagne, in his 789 Admonitio Generalis, set new standards for copying texts, including the adoption of a new more uniform and more legible script to replace the various, and often nearly illegible, regional styles. This script, Carolingian (or Caroline) minuscule, was based on the Merovingian and Germanic scripts and the Roman half-uncials and featured an uncial d, a modern a and g, and clubbed ascenders.

Most importantly, and this was kind of the point, Carolingian minuscule set a new standard for legibility. It employed a a systemized hierarchy of scripts, a clear difference between majuscule and minuscule forms, relatively few ligatures or stylistic flourishes, and perhaps most importantly, spaces between the words.

Gospel book, Tours, ca.820–830

Drogo Sacramentary, Metz, ca.850

Sacramentary of Charles the Bald, Metz, ca.870

The script spread from Charlemagne’s scriptoria at Aachen, Corbie, Lyon and Tours and by the 11th century was used in most of Europe. It was eventually replaced by the various gothic scripts.

It would be difficult to overestimate how influential Carolingian minuscule would become, although this was largely by accident. When Sweynheym and Pannartz, working for the Benedictines at Subiaco, were looking for ancient Roman exemplars for their humanist designs they mistakenly choose ninth century carolingian minuscule texts. The early Italian type cutters, such as Jensen, followed Swynheym and Pannartz’s lead, and the uppercase and lowercase alphabets and word spacing have become the standard of western typography to this day.

1. J. Deshusses, Le sacramentaire de Gellone dans son contexte historique. Ephemerides liturgicae 1961 75: 193–210.

2. Specifically: Bibliothèque nationale de France Latin 12048. For more details see the wonderful 2007 online exhibition Trésors Carolingiens. The images here are all from the exhibitions’ Livres á feuilleter. Even more details of the manuscript are presented in the BNF Banque d'Images.

3. For more analysis of the manuscript see: A. Dumas, ed., Liber Sacramentorium Gellonensis. (Corpus Christianorum ser. Lat. CLIX). Turnholti: Typographi Brepols Editories Pontificis, 1981, or Chazelle, Celia. The Crucified God in the Carolingian Era: Theology and Art of Christ's passion. Cambridge; Cambridge University Press, 2001.

4. Bischoff, Bernard. Latin Paleography: Antiquity and the Middle Ages. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1990.

5. Where “the situation as a mess” really means that the situation was far too complex for your humble narrator to deal with. I may revisit some of this material in the future but don’t hold your breath. In the meantime see Dianne and Jack Tillotson’s excellent Medieval Writing site for much more detailed review of these scripts, as well as a more general primer on paleography.

23 Dec 2009 ‧ Typographia Historia