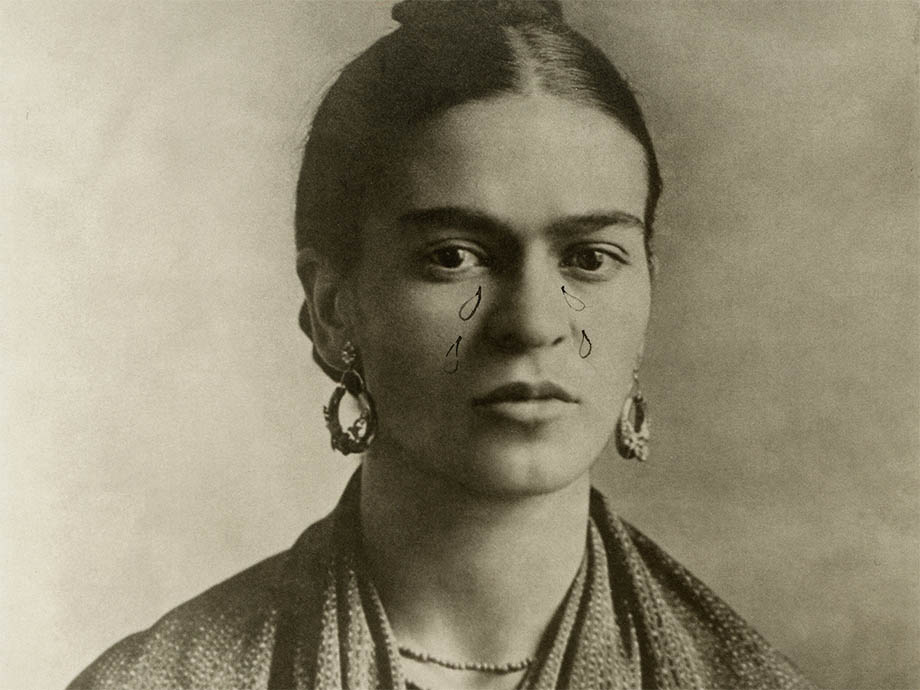

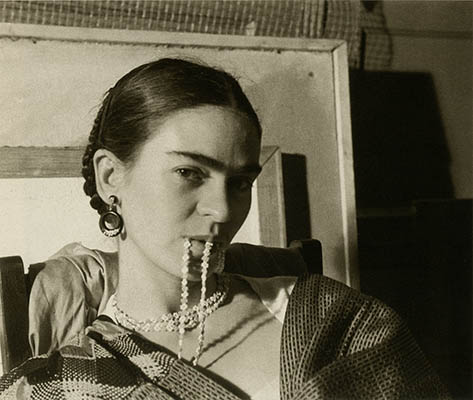

This photograph of the artist Frida Kahlo was taken in Oct 1932 by her father Guillermo.1 The silver gelatin print, a gift to her childhood friend Isabel Campos sent after the sudden death of her mother Matilde, was inscribed with “De tu amigo que está muy triste” (From your friend who is very sad). If this wasn’t already evident, she further annotated the photo with drawn tears. It’s a beautiful image and presages her recurrent themes of pain and sadness in her art.

Frida was born into a photographic family. Her paternal grandfather sold photographic supplies in Baden-Baden, her maternal grandfather was a studio photographer in Oaxaca and by the time she was born in 1907 her father had become a quite successful photographer in Mexico City.

By all accounts Frida was Guillermo’s favorite daughter and he taught her not only the technical aspects of his profession but the artistic ones as well. By the time she was a teenager she could not only operate a camera, develop film and print photos, but had learned quite a lot about staging and composition.

Guillermo Kahlo. Frida at 11 years old, 1919. Google Art Project

Guillermo Kahlo. Frida at 18 years old, 1926

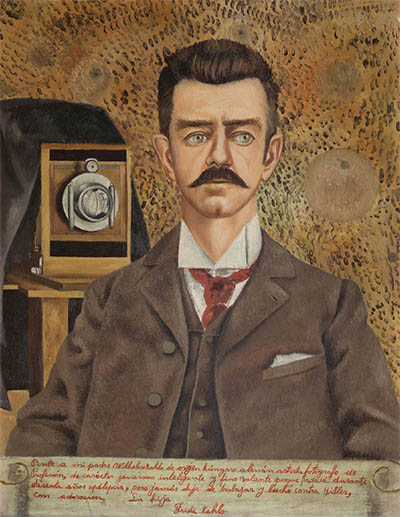

In 1925 Frida was involved in a horrific bus accident and spent a month in a hospital where “death dances around my bed at night.” While recuperating in a plaster corset she began to paint self-portraits from a mirror – her paintings completely informed by her father’s training in composition. Guillermo had hoped that she would follow in his footsteps and become a photographer, but she ended up doing even more – she spent her life channeling him through her art:

Portrait of my Father Wilhelm Kahlo, 1952. Google Art Project

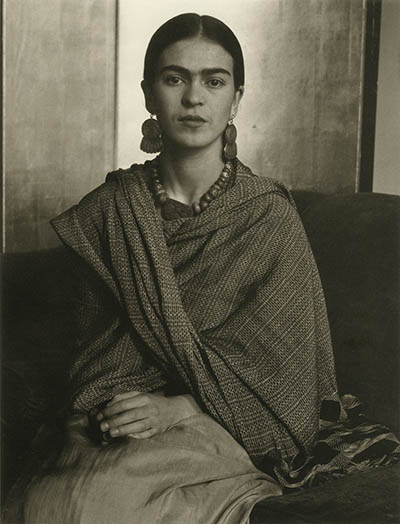

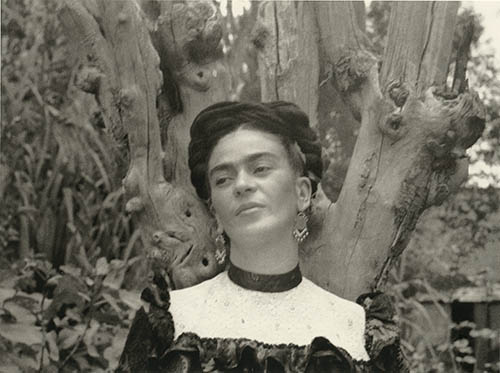

Even as a young girl Frida had a self-assuredness in front of the camera, but by her twenties she had internalized the composition lessons of her father. She could project any specific image she wanted portrayed. As Diego Rivera’s young, beautiful and fiery wife, she proved an irresistible subject for portraiture. After meeting her Edward Weston wrote in his daybook “[she was] a little doll alongside Diego... People stopped to look in wonder.” She would be photographed by a who’s-who of early 20th century masters including Weston, Imogen Cunningham, Martin Munkacsi and Lola Álvarez Bravo.

Edward Weston. Frida Kahlo, 1930

Imogen Cunningham. Frida Kahlo, 1930

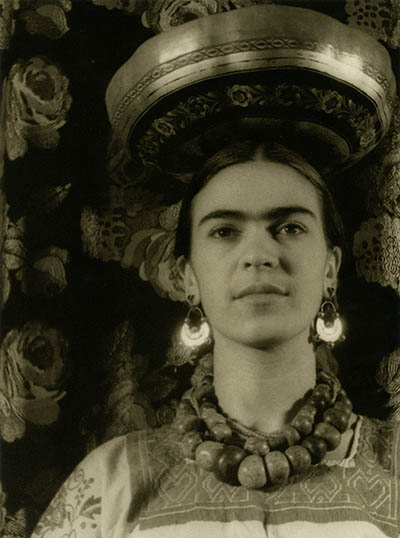

Carl Van Vechten. Frida wearing a Tchuantepee gourd, 1932

Lucienne Bloch. Frida biting her necklace, 1933

Nickolas Muray. Frida painting The Two Fridas, ca.1938

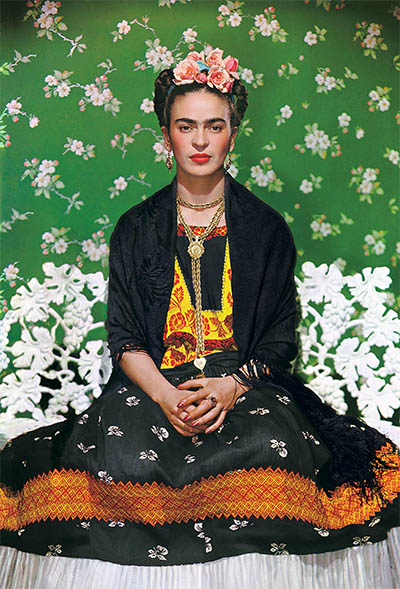

The most intimate portraits of Frida would be taken by her lover, the Hungarian-born master of color Nickolas Muray. Shortly after her marriage to Rivera, Frida began a decade-long on-again, off-again affair with Muray. These images, taken in his New York studio at the height of their romance, are perhaps the most beautiful and iconic portraits of Frida.

Nickolas Muray. Frida Kahlo, 1939. George Eastman House 2

Nickolas Muray. Frida on White Bench, New York, 1939

Nickolas Muray. Frida lying down, 1946. Google Art Project

Frida’s portraits hide as much as they reveal. The Tehuana dress and pre-columbian jewellery, especially later in her life, were carefully designed to conceal what she though were her physical imperfections. She was, as she wore in her diary “la gran ocultadora” (the great concealer).

Lola Álvarez Bravo. Frida leaning against a tree, 1942

Leo Matiz. Frida Kahlo, 1946

The injuries from her bus accident would plague Frida for the rest of her life. She endured countless surgeries and convalescences that would leave her bedridden for as long as nine months at a time. Her right leg was amputated in 1953 and after bout with pneumonia she died on 13 Jul 1954, only days after writing in her journal “I hope the exit is joyful – and I hope never to return.” 3

Among her archives, unsealed 50 years after her death, were more than 6500 photographs.4 It included her fathers work, her famed portraits, images of her lovers, friends and family, even her home and her pets. To Frida the photographs were important objects. Not just keepsakes but the visual document of her life; her way of saying “Here I am, do not forget me.”

Juan Guzmán. Frida holding a mirror in the hospital, ca.1951

Lola Álvarez Bravo. Frida on her death bed, 1954

1. Unless otherwise noted these images are from: Hooks, Margaret. Frida Kahlo, Portraits of an Icon. London: Bloomsbury, 2002 (WorldCat).

2. This was – aside from her father’s work – her favorite portrait. After receiving the print she wrote to Muray: “Nick darling. I got my wonderful picture you sent to me. I find it even more beautiful than in New York. Diego says that is is marvelous as a Piero della Francesca. To me is is more than that, it is a treasure.”

3. The coroner ruled the death a pulmonary embolism, although no autopsy was performed. Many consider her death, based on her diary entries and letters to her physician, a suicide.

4. For more information see: Ortiz Monasterio, Pablo. Frida Kahlo: Her Photos. Mexico City: Editorial RM, 2010 (WorldCat).

12 Jun 2013 ‧ Photography