Robert (Bob) McCall was born in Columbus, Ohio on 23 Dec 1919. Although he always had a strong interest in popular science and science fiction he knew, even as a child, that he would become an artist. After attending the Columbus Fine Art School on scholarship he served in the Army Air Corp during the War. In 1946, with his new bride Louise (an artist herself) he moved to Chicago a began a career in commercial art. By 1949 he was in New York where freelanced as an editorial and commercial illustrator.1

Although he did any commission he could get, including romance illustrations for The Saturday Evening Post and outdoor illustrations for Field and Stream, his heart was still with the popular science topics of his childhood – aviation, aeronautics and aerospace. He was soon doing editorial work for Popular Science and commercial work for Boeing, Northrop and General Dynamics.

This work caught the attention of the Air Force who invited him to participate in their new art program.2 Eventually he contributed more than 45 paintings.

B-24s over Ploesti, Romania, August 1943, ca.1955

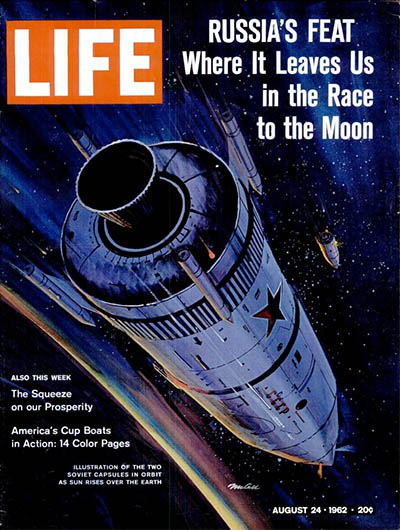

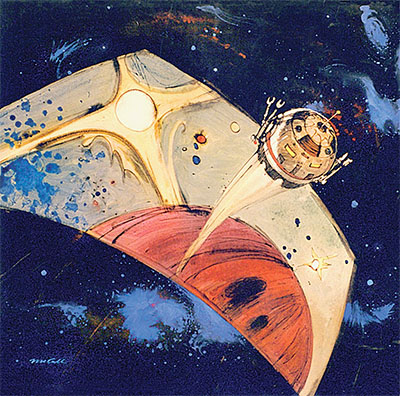

In 1956, in what he later called a “defining moment,” Life magazine commissioned him to illustrate the space race. His dramatic vision of the future was both technically accurate and wildly imaginative. Perhaps more than any artist of the time, he captured the excitement and optimism of the early efforts in space.

All of this high-exposure work led him to be selected as one of the first artists to contribute to the NASA Art Program. Beginning with the last Mercury launch in 1963 McCall would document the American Space Program.

Apollo 8 Coming Home, 1969. NASM

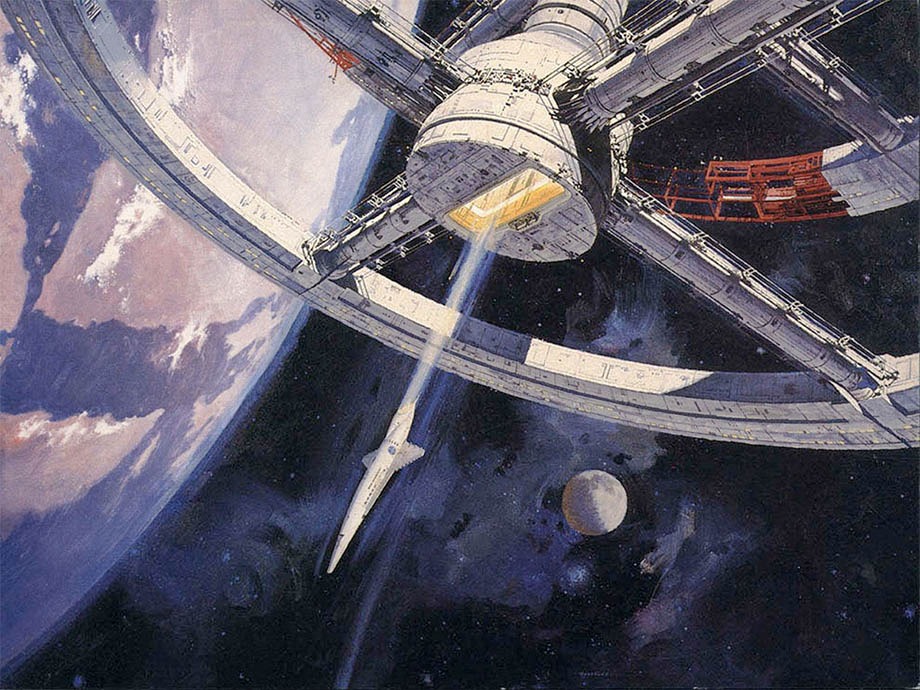

Stanley Kubrick and Arthur C. Clarke became aware of McCall through his work for Life. As he was completing production on 2001 Kubrick invited McCall to the MGM Studios in Borehamwood to prepare some conceptual drawings. McCall eventually spent spent three months in England working on illustrations for the film.

Concept art, 1968

For a director so famously concerned with verisimilitude, down to the last minute detail, the choice of McCall was perfect. His illustrations captured Kubrick’s vision of the future but made that vision look like a NASA promo piece – as if it was science rather than science fiction.

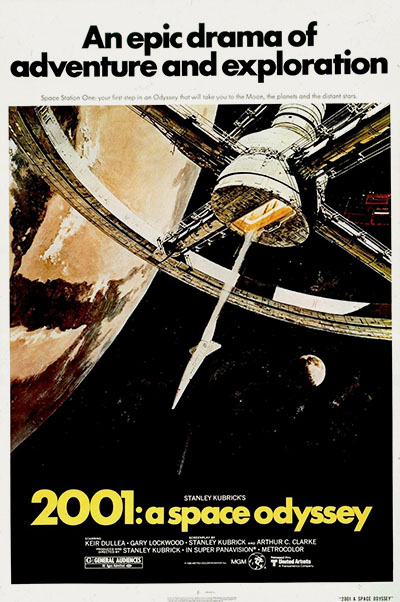

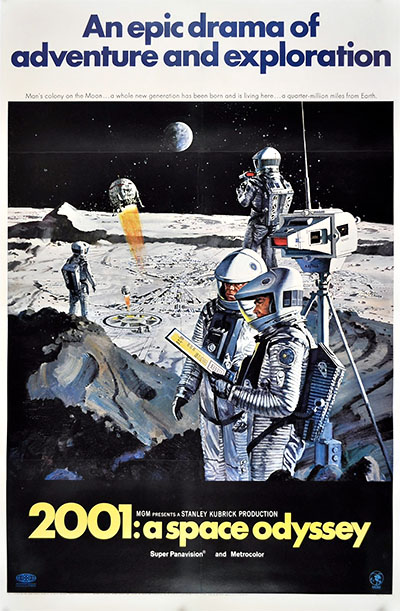

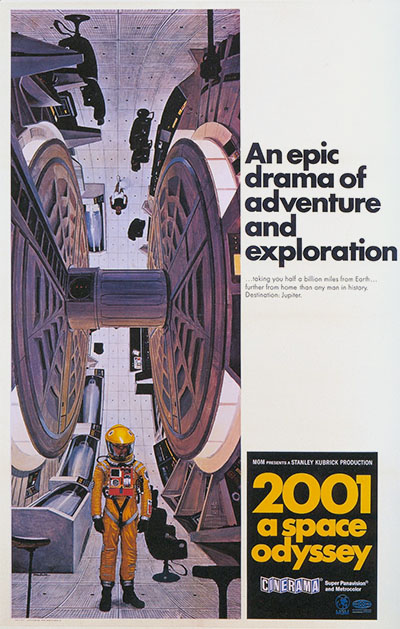

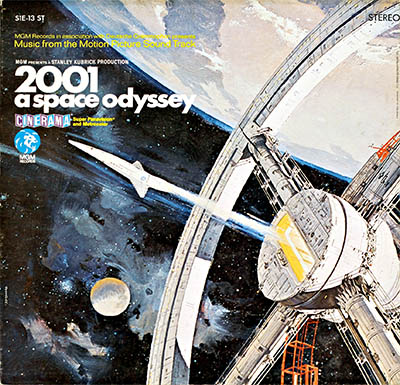

McCall’s illustrations (along with stills from the movie) became the basis of MGM’s marketing. They appeared on theater marquees, posters, lobby cards, programs, print ads - even on record albums.3

Orion Leaving Space Station One, 1968

Clavius Base, 1968

The Centrifuge, 1968

And here’s that album cover:

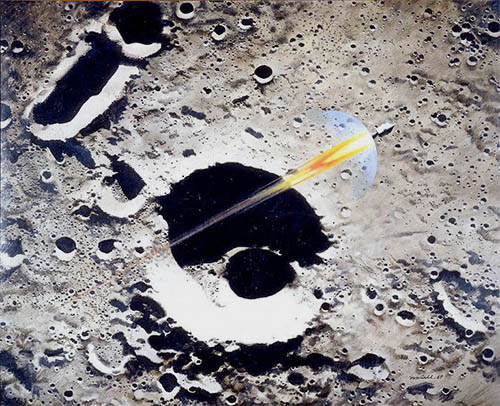

His work on 2001 led McCall to several more film commissions, including the Black Hole and Star Trek, but his passion was still with actual space travel. During the 1970s and 80s he continueed to document, often at his own expense, every NASA milestone including the Apollo, Apollo-Soyuz, Skylab and the Space Shuttle programs.

First Man on the Moon, 1970. NASA

Handshake in Space, 1974. NASA

McCall’s work appeared on not only canvas, but on postage stamps, official mission insignia and finally, as a capstone to his long career, on several murals, including at the Air and Space Museum and the Johnson Space Center. He had become, in the words of Isaac Asimov, the “nearest thing to an artist in residence from outer space.”

Detail, Opening the Space Frontier, The Next Giant Step, 1979. NASA

1. For more information about McCall and his art see the McCall Studio site.

2. McCall wanted to be a B-29 pilot, but because of his color-blindness, be ended up being a bombadier. This color-blindness, however, didn’t stop him form being an artist.

2. The United States Air Force Art Program began in 1950. Artists (typically illustrators) were invited to visit bases and observe exercises then document them in a way that would show the public the activities of the then new branch of the military. NASA used the Air Force program as the model of their own Art Program, begun in 1962. It was, according to the director James Dean, “an effort to present NASA's discoveries and cutting-edge research to the public in a way that would be more accessible than complex scientific reports.” In addition to McCall, other early artists included Robert Rauschenberg, Norman Rockwell and Jamie Wyeth.

3. True story: I first saw 2001 in the early 1970s when I was perhaps eight or nine years old. The fact that I got to go see a movie in a theater with my Dad on a school night was awesome enough but the movie completely blew me away – until I fell asleep, because – you know – I was only eight. Looking back I can only imagine what the 8-yo me would have thought had he stayed up for the stargate sequence.

2 Jun 2013 ‧ Illustration