The Paige Compositor

Twain, Paige and the Machine that Destroyed Them

“I must speculate in something, such being my nature,” Mark Twain told his editor William Dean Howells in 1883. Indeed, over his life Twain had invested—and lost—on dubious schemes ranging from a new engraving process to a novel magnetic telegraph to a miracle protein powder (which could “end the famine in India”). But among his many investments it was James Paige’s Compositor—a dazzling machine that promised to revolutionize the printing industry by completely automating hand composition—that had truly captured his imagination (and later his wallet). While Twain didn’t know much about engraving or magnetics or, for that matter, proteins, he intimately knew printing and was “entirely certain that the [Compositor] would turn up trumps eventually.”

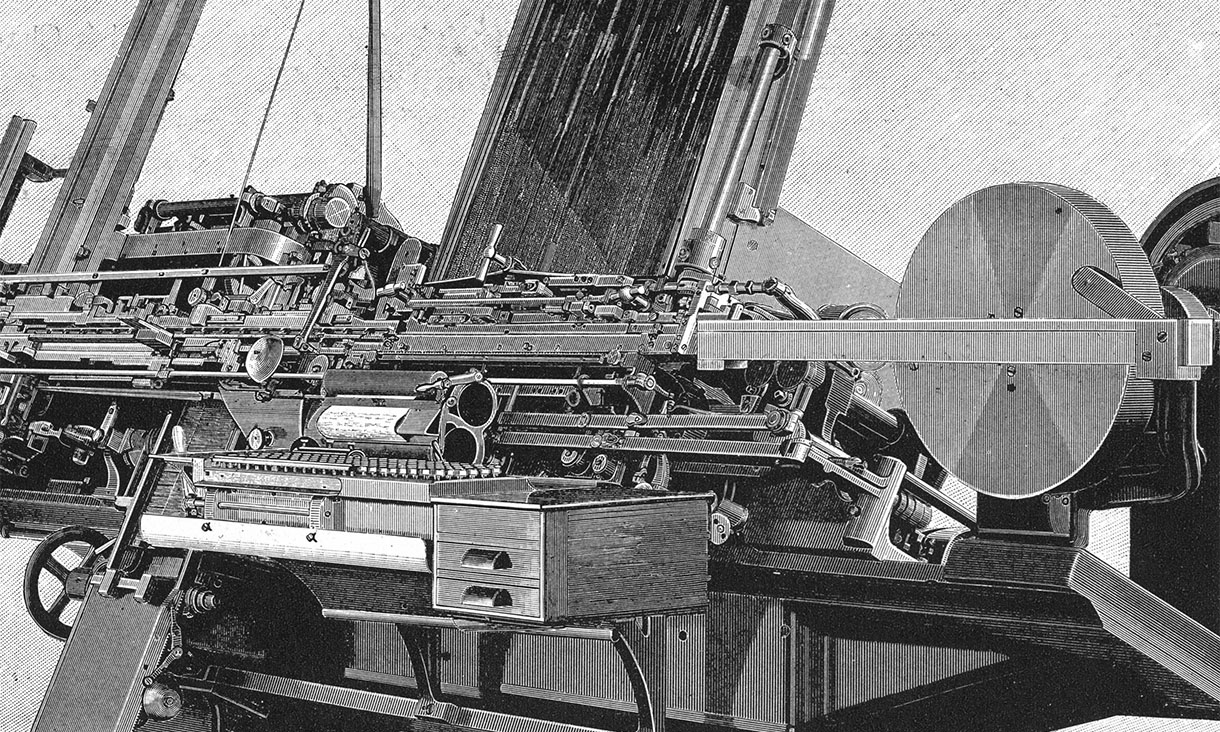

The 1911 edition of the Encyclopedia Britannica called the Compositor “one of the most remarkable pieces of mechanism ever put together.” Legros and Grant, in their classic, Typographical Printing-Surfaces, said it was “the formost example of cam mechanism ever produced in the United States.” However, Albert Paine, Twain’s official biographer, called it “a remorseless Frankenstein monster.” As it turned out, the Compositor was all of these things.

I.

In 1848, a year after his father died, Samuel Langhorne Clemens of Hannibal, Missouri, left the fifth grade to began an apprenticeship as a printer’s devil for the Missouri Courier. Two years later he become a typesetter for his brother’s paper, the Western Union. Promising his mother that he wouldn’t “throw a card or drink a drop of liquor,” he left Hannibal at the age of 17 and spent the next four years as a travelling “jour” printer; first in St. Louis (where it was noted that “he could not have set up an advertisement in acceptable form to save his life”), then New York, Philadelphia, Iowa and finally, Cincinnati.

In 1857 Clemens left the printing trade to seek his fortune in South America but made it only as far as New Orleans, where he became a steamboat pilot on the Mississippi. Later he became a Confederate irregular, correspondent, editor, inventor, investor, prospector and publisher. Of course along the way he also became Mark Twain and wrote the novel that, as Hemingway said, “all modern American literature comes from.”

While Twain is perhaps the most celebrated and studied American of the 19th century, James William Paige was an enigma—there isn’t even a known photograph of him. He was likely born in January 1842 in Rochester, New York and spent his youth with his father in the oil fields. Although he wasn’t a printer by trade, he was certainly mechanically inclined and at the age of 30 applied for a patent for “a device, by means of its special construction, to set type more rapidly and accurately than has been before done.”

In 1877 the Farnham Typesetting Company, operating out of a workshop in the Colt Arms factory in Hartford, Connecticut, asked Paige to combine his newly-patented typesetter with their distributor. Paige soon found that marrying the two machines was impossible. Rather than simply drop the matter, however, he began building a completely new machine—the Paige Compositor.

Twain first met Paige in 1880 on the urging of his friend (and Farnham stockholder) Dwight Buell. At first Twain was skeptical: “I knew all about type-setting by practical experience, and held the settled and solidified opinion that a successful type-setting machine was an impossibility.” After seeing Paige’s prototype in action, however, he changed his mind. “[Its] performance did most thoroughly amaze me.” By this time Twain had some success with The Adventures of Tom Sawyer and was willing to take a risk, telling a friend that he was “always taking little chances like that—and almost always losing by it, too.” He bought 2000 dollars, then another 3000 dollars of Farnham stock and later wrote “it is here that the music begins.”

Paige, whom Twain described as “a small, bright-eyed, alert, smartly dressed man,” was, if nothing else, a convincing spokesman for his obsessive vision; “He has a crystal-clear mind...He is a poet; a most great and genuine poet, whose [sublime] creations are written in steel. He is the Shakespeare of mechanical invention.” But Twain also noted that Paige “is an extraordinary compound of business thrift and commercial insanity.” In other words, he was no different than Twain himself.

II.

The industrial revolution had brought great advances to commercial printing. Fourdrinier invented the continuous-roll paper machine in 1806. Koenig invented the steam press in 1811 and Hoe introduced the rotary press in 1846. Less successful, however, were attempts to mechanize composing. To replace hand composition, the most labor-intensive part of printing, a machine had to select the appropriate type, compose and properly space (justify) the type into a line of text and then, after printing, correctly return the used type back into the machine. It would be one of the great mechanical challenges of the late 19th century. Church (1822), Young and Delcambre (1840) and Mitchel (1853) all tried designing mechanical typesetters, but by the time the young Samuel Clemens was setting type in Hannibal he was still using a composing stick the same way Gutenberg had done in Mainz 400 some years earlier.

Paige studied the work of practicing composers and tried, wherever possible, to design mechanisms that would replicate their hand movements with gears, cams and an inspired level of machine logic. When Twain next saw the Compositor in early 1886, now being built at the Pratt and Whitney factory in Hartford, it could successfully set and automatically redistribute type. He wrote “a setter and a justifier could turn out about 3,500 ems an hour on it; possibly 4,000. There was no machine that could pretend rivalry to it.” Here, he said, was a typesetter that “does not get drunk, does not join the Printers’ Union [and] does not distribute a dirty case.”

On February 6th, 1886, Twain signed a contract with Paige, not only financing the completion of the Compositor but agreeing to capitalize and promote it in exchange for half of the profits. His business partner warned that this could bankrupt him but Twain, flush with the receipts from a recent speaking tour and royalties from Huckleberry Finn, didn’t seem too worried. “I can get a thousand men worth a million apiece to go in with me,” he wrote, “then I can get a perfect machine.” Twain began doing some back-of-the-envelope calculations and determined that the Compositor could be worth millions, perhaps hundreds of millions of dollars. He told his nephew that it would take ten men just to count his profits.

Twain pledged another 30,000 dollars to complete the machine. Paige, however, thought the Compositor needed a mechanical justifier. Rather than try to shoehorn one on to the existing machine he redesigned and rebuilt the machine from scratch. It was a “total violation of [our] agreement,” Twain said. The 30,000 dollars lasted about a year but the justifier assembly took nearly four years to complete. Eventually Twain was financing Paige to the tune of some 4000 dollars a month—including not only his book royalties, but a good portion of his wife Olivia’s inheritance as well.

III.

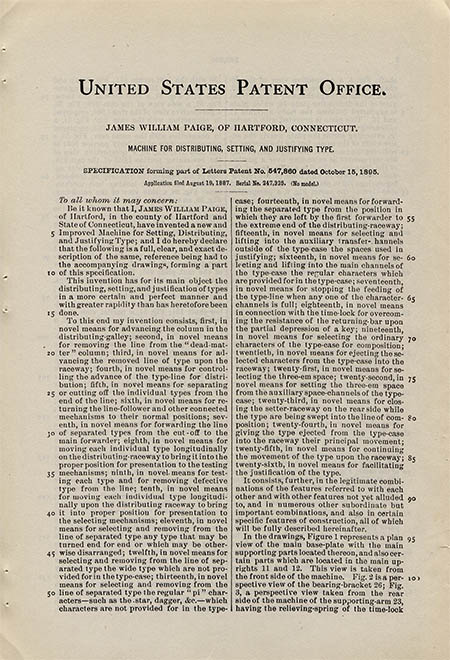

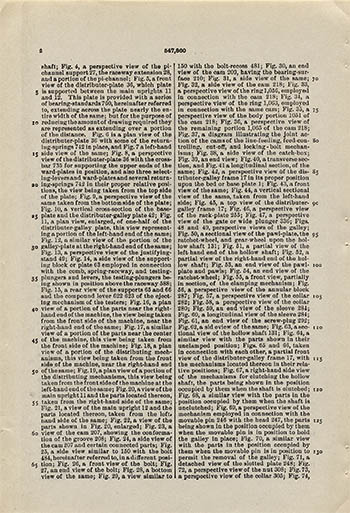

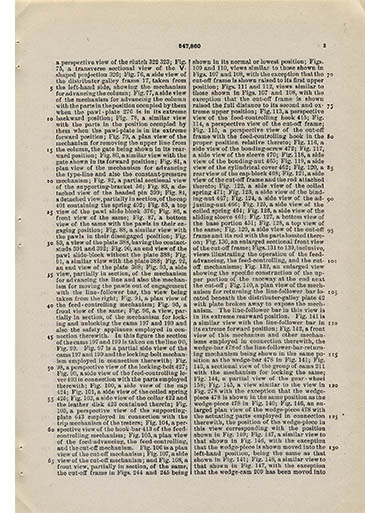

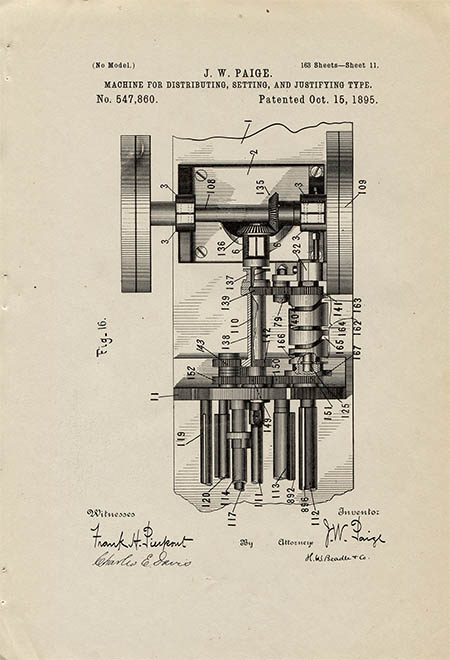

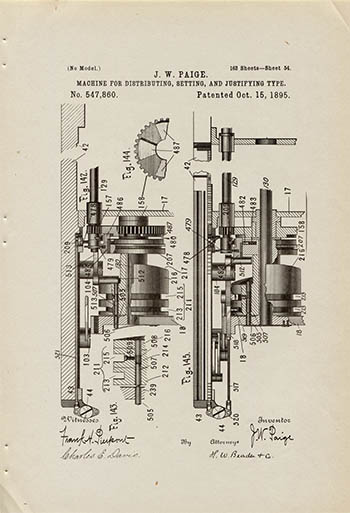

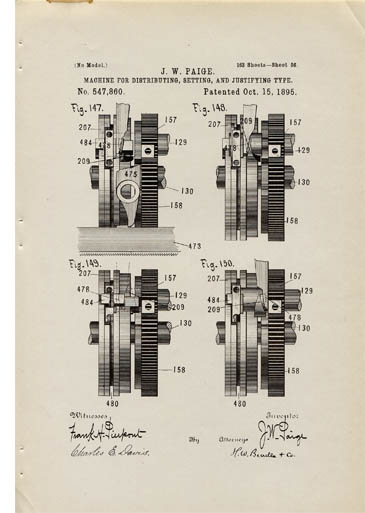

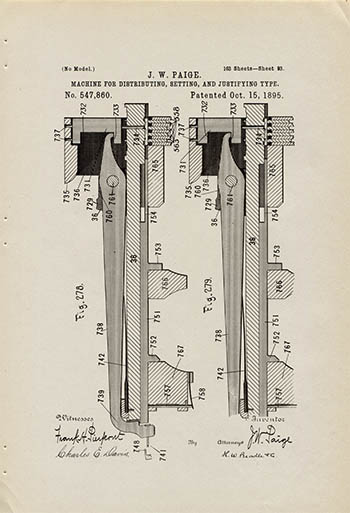

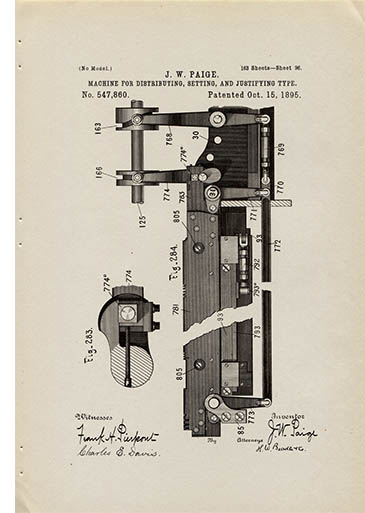

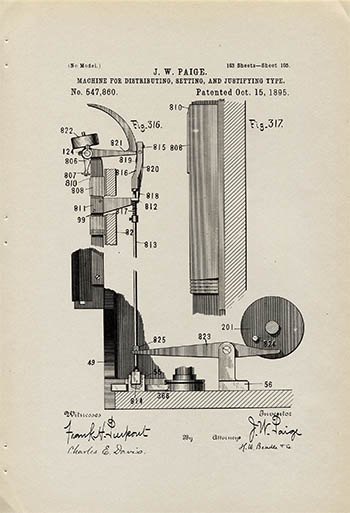

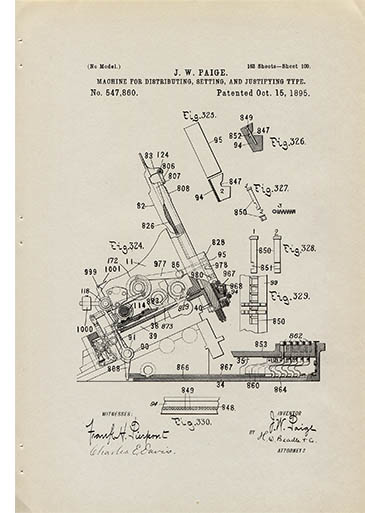

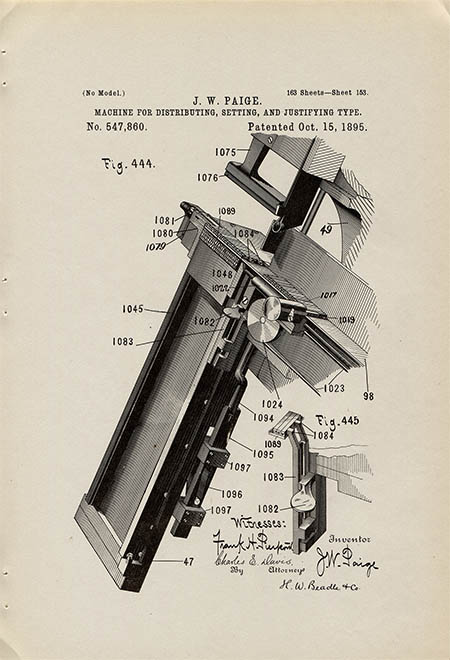

By late 1887 Paige thought the Compositor was sufficiently complete to apply for a patent, or more specifically, for three separate patents which included more than 440 claims supported by more than 850 figures. “[Paige] evidently became lost in the wilderness of appalling details,” said his attorney David Fletcher, “The machine was, regardless of construction, function or operation, divided into Three ‘Grand Divisions.’ Each division was in turn, divided into subdivisions, and these again divided until the ‘Sixteenth sub-sub-division’ was reached.” The application was so convoluted that Fletcher had to completely rewrite the specifications.

The second of the patents—concerning the composer and the distributor—was 218 pages long. It was the largest application ever received by the Patent Office and earned the nickname “the Whale.” Because Paige, obviously, couldn’t provide a model, an examiner spent a month on site with the machine. In all it took eight years for the Patent Office to approve Paige’s applications. One examiner died during review and the rumor was that yet another went insane.

IV.

While Paige was trying to perfect his Compositor other inventors were also trying to solve the problem of mechanical composition. In 1872 the German watchmaker Ottmar Merganthaler immigrated to Baltimore and soon begin working on his own typesetter. Unlike Paige, he was unconcerned with replicating hand movements and developed a completely different, and relatively simpler solution. Rather than using thousands of individual pieces of foundry type like the Compositor, Merganthaler’s machine—the Linotype—used brass matrices, inspired by the traditional cookie molds of his childhood, to cast a single line of type out of molten lead. As soon as the line was cast the few dozen or so matrices were distributed back into the machine. After the cast-lead slugs were used for printing they could simply be melted down and used again.

Merganthaler’s first version of the Linotype was installed at the New York Tribune in 1886 and the next year it was used to compose the 500-page Tribune Book of Open-Air Sports. Still other typesetters, including the Rogers Typograph and the Thorne Simplex, were being tested in pressrooms as well.

Twain was well aware of these developments but his inside sources at the Tribune told him that the Linotype was both slow and unreliable. After Twain, Paige and his engineer saw Merganthaler’s machine in action Twain wrote “we considered it liberal to call it a 3,500-em machine.” By that time the Compositor was reportedly operating at a rate of 5000 ems an hour and he was sure that it would eventually put Merganthaler out of business. He wrote in his notebook, “I [am] unaffrighted [and] am still at work building my type-setter.”

In January, 1888, Paige promised Twain a finished machine by the 1st of April. In April he promised it for September, and in October he promised it in another two or three months. Finally, on January 5th, 1889, Twain saw the supposedly completed Compositor. “Eureka,” he wrote in his notebook, “I have seen a line of movable type spaced & justified BY MACHINERY! This is the first time in the history of the world that this amazing thing has ever been done.” He wrote to his friend in London, “a death-warrant of all other type-setting machines in this world was signed at 12:20 this afternoon.”

However the Linotype wasn’t quite dead yet and the Compositor wasn’t quite finished yet. As Paige worked on his typesetter, so too did Merganthaler. A new, more reliable version of the Linotype was built in 1890 and by the end of 1891 there were some 300 in operation at more than 20 different newspapers.

V.

By this time Twain’s publishing house had collapsed and the family was having financial troubles. His book royalties weren’t even enough to cover the household expenses, yet he continued to sign notes financing Paige and the Compositor—“a foot farther into the ledge and we shall strike the vein of gold,” he wrote. “When the machine is finished everything will be all right again,” he told his wife. Reporters remarked that his literary success had made him crusty and sour, but it wasn’t his successes, it was his financial failures that were now weighing on him.

Eventually Twain, along with the financier Joseph Goodman, organized a capital-stock company to sell off some of his interest. He contacted Senator John Jones, a friend from his Nevada prospector days, but when Twain took him to see the Compositor in January, 1890, it was in parts on the floor—Paige decided the machine needed an (unnecessary) air-blast and had yet again dismantled it. Jones left unimpressed and never did invest. Soon Twain was offering a twentieth or a hundredth or a thousandth part of the enterprise, but found few takers. In June, 1891, partly for health reasons and partly to escape their financial troubles, Twain and his family left their Nook Farm home for Europe. He had apparently given up on Paige; “I have shook the machine & never wish to see it or hear it mentioned again,” he wrote.

VI.

It had become clear to the newspaper industry that it wasn’t a matter of if mechanical composition would take over the pressroom, but rather when and how. The trade journals of the day, including the Inland Printer and the Journalist, were filled with articles (and advertisements) describing new typesetters and linecasters. In October, 1891, the American Newspaper Publishers’ Association (the ANPA) organized a competition of various typesetters. Notably absent was the Compositor; Paige told the organizers that a public exhibition would interfere with his pending patents.

In his report, committee chairman Fredrick Driscoll said that the Rogers Typograph had won the contest, producing the best and most economical results. The Linotype, he said, because of its delicate and complicated mechanism, fell short of the claims of its inventor (although he also noted that the Linotype operator was both reckless and sulking during the trial).

In early 1892 Paige persuaded the ANPA to conduct a private test of the Compositor in Hartford and the results were nothing short of stunning. At times the Compositor reached speeds more than twice what the Typograph or the Linotype could do. The committee was greatly impressed with the ingenious construction of the machine and reported no drawbacks. Their report was so favorable that Paige quickly prepared a prospectus and soon several papers made provisional orders.

That same year Merganthaler built another, even better, version of the Linotype and, perhaps even more importantly, won a patent infringement case against Rogers and his Typograph, effectively removing it from the market. By the end of 1892 there were more than 500 Linotypes in operation.

VII.

Others were paying attention to these developments and in 1892 a consortium of New York businessmen, known only by their last names of Ward, Frink and Kneval established a new firm, the Compositor Company, which contracted with the Webster Manufacturing Company in Chicago to build a new model of the Compositor en masse. In March, 1892, Paige moved his disassembled machine in a 10-ton safe from Hartford to Chicago with “every precaution being taken to prevent loss or disclosure.”

Paige told the New York Times that the company would employ 500 men building some 4000 secured orders at 20,000 dollars apiece. The venture, he said, was backed by six million dollars in capital. While at Pratt and Whitney every gear and cam was built by hand, the new company would have vast floors of machines dedicated to building parts for Compositors.

Twain had returned from Europe on business in 1892 and 1893 and once again became excited about the prospects for the Compositor. Perhaps, he thought, his long sought-after payoff was finally in sight. Nevertheless, after 20 years of delays, he still doubted Paige’s ability to deliver. After he met Paige in a Chicago hotel in 1893 he wrote: “Paige shed even more tears than usual. What a talker he is. He could persuade a fish to come out and take a walk with him. When he is present I always believe him; I can’t help it.”

The Compositor Company’s 4000 secured orders became 50, then 10 and finally just one. They hoped to demonstrate the machine at the 1893 Columbian Exposition (the Chicago World’s Fair), but a working prototype simply wasn’t ready in time.

In February, 1894, Twain, with the industrialist Henry Rogers (of Standard Oil fame), entered into yet another contract with Paige. Twain had lost on every other investment scheme and now the Compositor was the only thing he had left. But

things appeared to be looking up; in September James Scott, president of the ANPA and publisher of the Chicago Herald & Post, agreed to test the finally completed Compositor in his pressroom.

VIII.

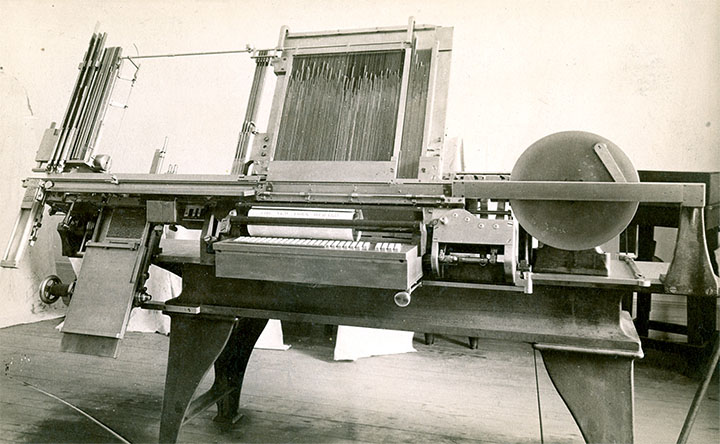

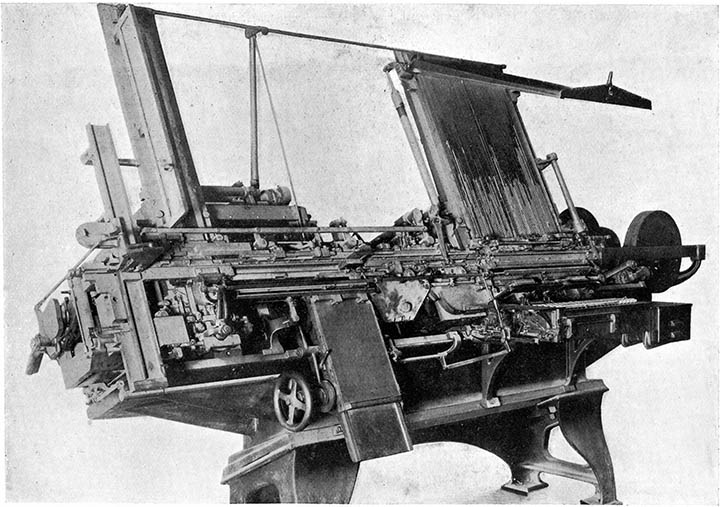

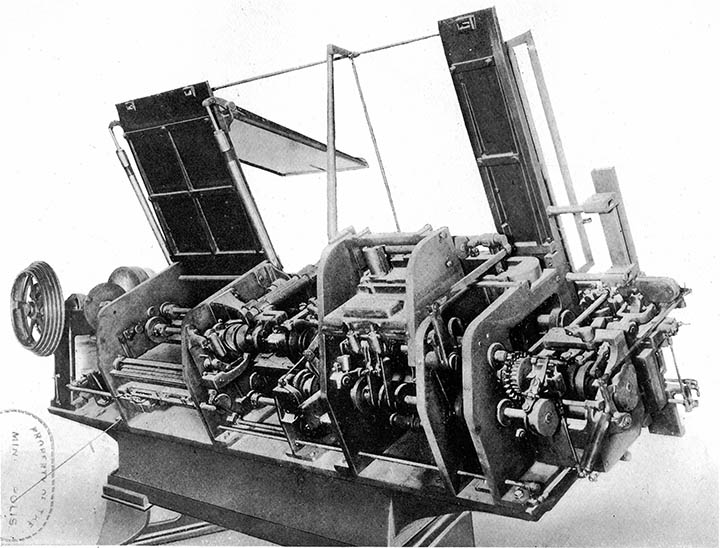

The Compositor was a testament to Paige’s singular vision and ingenuity— It was like a Jacquard loom that could unravel and rewind what it had just weaved. The keyboard allowed syllables—even complete words—to be instantly composed. The justifier utilized 11 different-sized spaces and was sensitive to hardly more than the width of a human hair. The distributor would independently return the type back to the magazine and even remove bent or dirty type. An mechanical “time-lock” would automatically stop the machine if there was a problem and even tell the operator where the fault was. It was so automated that nearly anyone could use it; “The operator need only know how to read and punctuate correctly,” Paige said in his prospectus.

It was “as complicated as a French watch, and runs as smoothly as a chronometer,” wrote Journalist editor Allen Forman. L. L. Morgan of the New Haven Register stated that “there is probably no other other machine that is so attractive when working.”

“When working...” was the issue. With more than 18,000 parts including annular blocks, bearings, bearing brackets and standards, clutches, collars, combs, contact studs, cross bars, distributor plates, eccentric shafts, flywheels, gears, levers and lever arms, line-following bars, locking bolts, pawl plates, pins (hollow and moveable), rack plates, rings, screws and screw plugs, shafts and shaft bearings, springs (relieving and returning), supporting arms, testing plungers and levers, ward plates, wedge pieces and, especially, cams (and more cams, then even more after that), the Compositor was impossibly complex, delicate and temperamental.

When the 60-day trial at the Herald began on September 20th, 1894, the Compositor initially produced 9000 ems an hour and with a skilled operator as much as 12,000. It “delivered more corrected live matter to the imposing stone, ready for the forms, than any one of the thirty-two Linotypes in the same composing department.” Upon hearing the reports Twain was ecstatic, “It seems to me that things couldn’t well be going better at Chicago.”

But soon the Compositor began mangeling type and the delays began mounting. Paige had to be summoned to repair the machine; it was simply too complex for a composing room mechanic to understand, let alone fix. Eventually Scott stopped the trial. He found the Compositor unsuitable for the workaday requirements of a newspaper. Although the Compositor wasn’t particularly less reliable than the Linotype, Paige’s investors realized that they could never build an 18,000-part machine in commercial quantities and could never compete with the much less expensive Linotype (Twain’s royalty alone was almost half the cost of a Linoype). Several months later they dissolved the Compositor Company. Paige’s invention was now dead—Merganthaler’s Linotype had won the war.

At the time Twain was living in Paris and Rogers wrote to him with the news. “I seemed to be entirely expecting your letter, and also prepared and resigned. It hit me like a thunder-clap,” he wrote back. “I wish that you had been in at the beginning. Then we should have had the good sense to step promptly ashore.”

IX—Epilogue.

In all investors had poured some two million dollars into Paige’s grand vision. Twain himself lost more than 180,000 dollars (or more than five million in todays money) and in 1894 was forced to declare bankruptcy. However, through speaking tours and new books he eventually repaid all of his creditors. Although he made good on his debts, he never forgave Paige. In his autobiography he said, “Paige and I always meet on effusively affectionate terms; and yet he knows perfectly well that if I had his nuts in a steel-trap I would shut out all human succor and watch that trap till he died.”—a far cry from “the poet written in steel” that Twain had called him 20 years earlier.

Paige had once been worth 1.5 million dollars, but, according to the New York Times, had lost it all in the Panic of 1893. He died, penniless and alone, in an Oak Park, Illinois, poorhouse in 1917.

Twain had clearly bet on the right race, just on the wrong horse. Merganthaler’s Linotype, which he had so publicly derided, became one of the most important inventions of the 20th century. Thomas Edison, who knew a thing or two about invention, call it “the eighth wonder of the world.” At its peak in the 1950s the Linotype was used in more than 85 countries to compose material in several hundred different languages. It was the dominant typesetting machine until the introduction of computerized photo-composition in the late 1970s. The New York Times was composed using 64 Linotype machines until 1978. The National Archives and Records Administration employed an entire floor of Linotypes to compose the Federal Register until 1979.

This example—one of two ever built—was given to the

Mark Twain House in 1957.

—June 19th, 2012. Updated December 23rd, 2017. Typographica