Patty and Michael

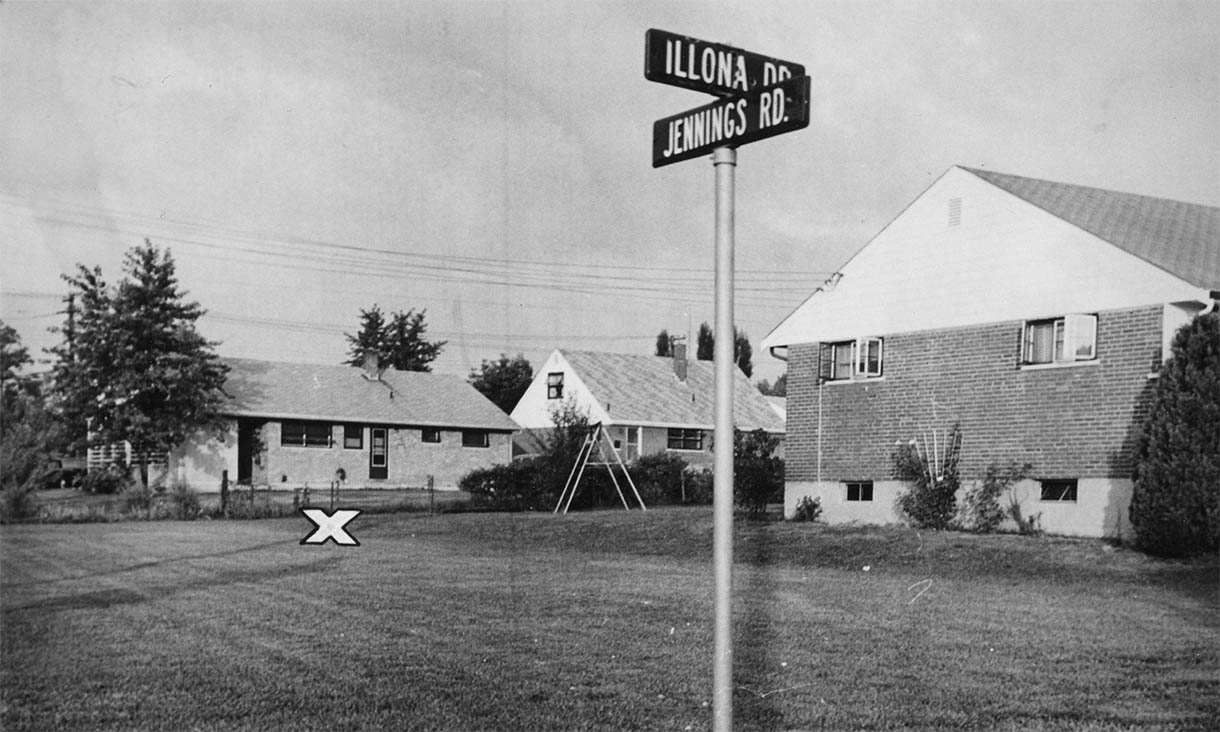

The Corner of Jennings and Illona

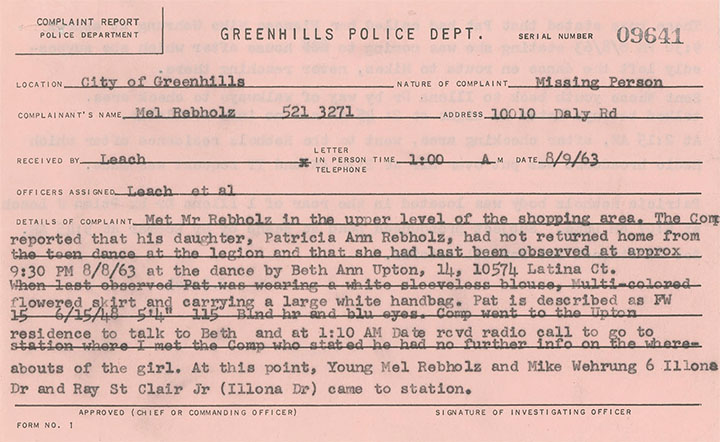

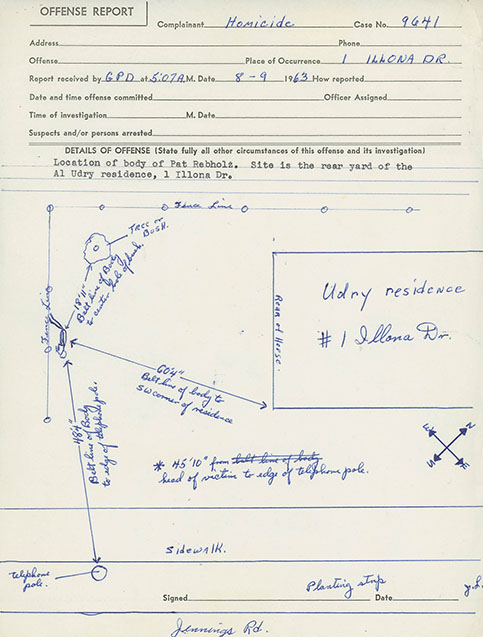

At 5:07 am on Friday, August 9th, 1963, patrolman Jack Leach was traveling north-west down Japonica Drive in one of the two patrol cars owned by the Greenhills Police department. As he turned left at the corner of Jennings Road and Illona Drive his headlights swept across Alphonse Udry’s side yard and he saw what he described as a “peculiar-looking mound.” He stopped his car, grabbed his flashlight, walked across the dew-covered lawn and found the body of 15-year old Patricia Ann Rebholz.

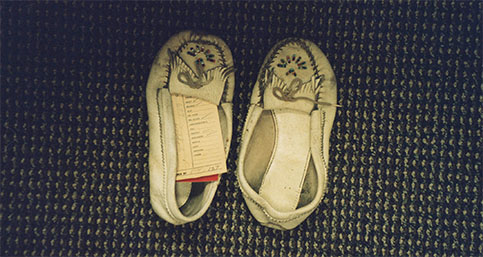

Leach had been with the department for four years but had never encountered anything even remotely like this before. His first instinct was to radio for backup and within minutes—13 minutes to be exact—chief John Baldwin and patrolman Randolph Morgan arrived. Morgan began circling the body taking photographs. Patty was lying on her side next to the wire fence at the property line—her moccasins doubled over her heels, her disheveled skirt pulled up around her waist and her handbag still dangling from her shoulder. Her head, blouse and even the grass beneath her was saturated with blood. Next to her head was a two-foot section of fence post which Leach noted was covered in dark stains, hair and “particles of what I believe to be flesh.”

As Morgan’s flashbulbs lit up the pre-dawn darkness, police from neighboring departments arrived and fanned out into the yard. Dr. Roemer, the local family physician, was summoned and pronounced Patty dead. Later, while the volunteer life squad was loading her body onto a stretcher, someone—it’s unclear exactly who—alerted 15-year old Michael Wehrung, Patty’s boyfriend of four months who lived just across the street. Only half-awake, Michael looked out his front door which had a direct view of the activity in the yard, turned to his sister Cheryl and asked, “Is she dead?” He then went back to sleep on the sectional sofa in his living room.

Why the police had taken all night to find Patty was one of the first of many questions about the case. Why Michael responded the way he did that morning was another. Why an activist judge shut down the initial investigation, then decades later, why a new prosecutor decided to reopen the case were yet even more questions. It’s now been more than a half century since Patty’s murder and for her friends and classmates—indeed, for the entire community of Greenhills—there are still more questions than answers.

I.

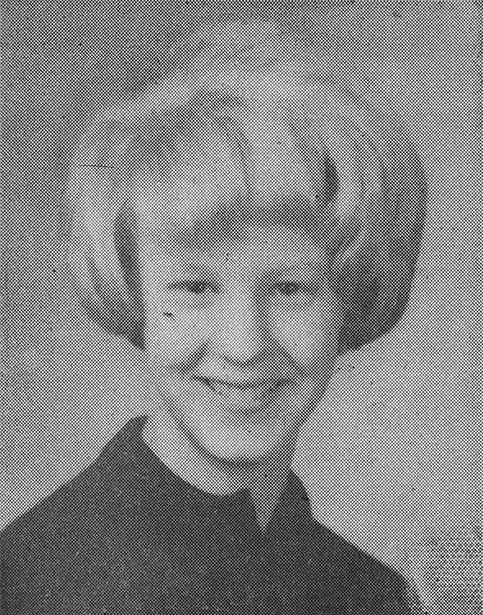

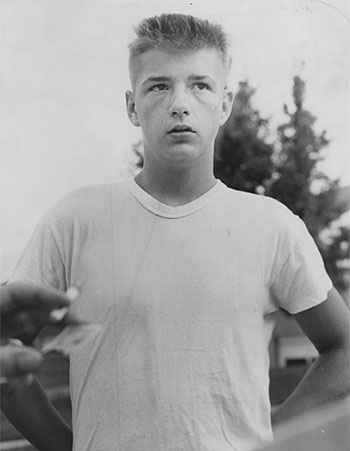

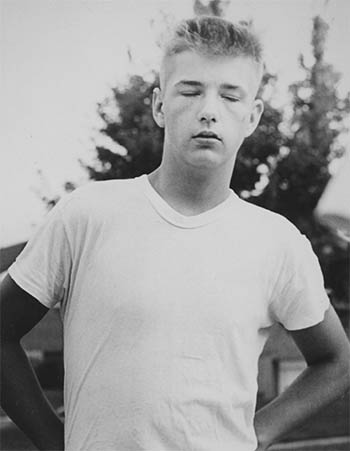

Michael first met Patty when they began attending middle school together. At the time, however, he was apparently busy with other girls. He first began dating at the age of 13 and by his count had already gone steady twice by the time he was 15. “He was cute and kind of dangerous, and the girls liked that,” said one classmate. Meanwhile Patty was becoming a petite blue-eyed blonde who had no problem attracting the attention of boys. “She changed so much over the next two years you wouldn’t believe it,” Michael said. “In the ninth grade she looked real tough.” Michael learned through Patty’s friends that she had something of a crush on him and they went on their first date in May 1963.

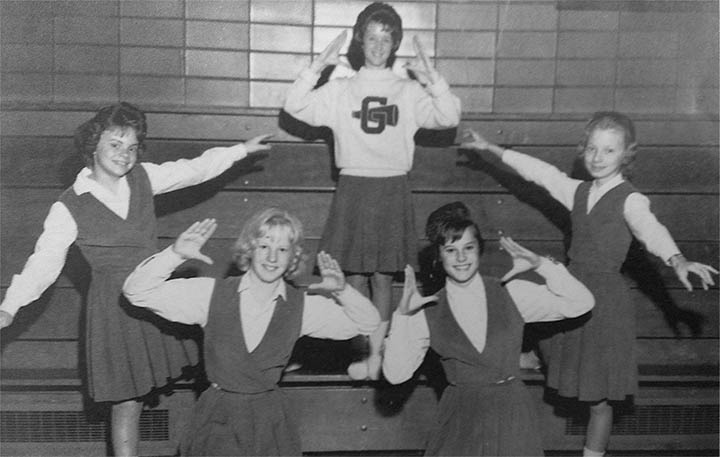

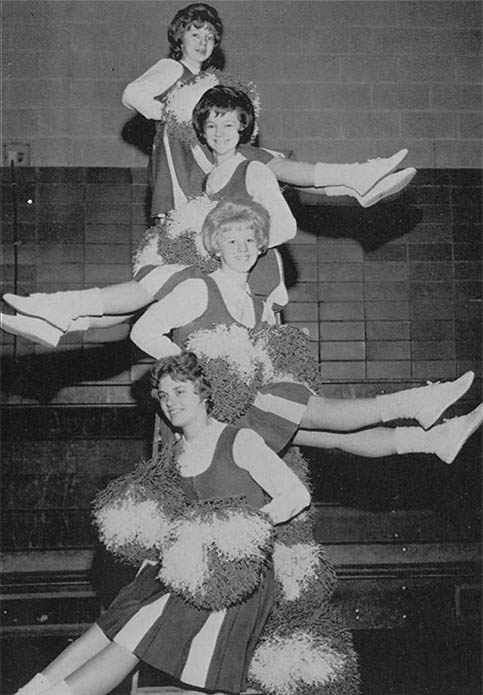

Their uniforms were green and white. Greenhills Pioneer, 1963.

To everyone who knew her Patty was sweet, outgoing and disarmingly friendly. “Girls rarely spoke to me. I was shy and self-conscious, but Patty always said hello like we were pals,” said a classmate. “She had a smile, even for the smallest children,” her father told a reporter. It was this easy manner and magnetic personality that made her one of the most popular underclassmen in school. She was a conscientious student and was active in the school band and chorus. She had been a cheerleader since middle school and was on the reserve squad as a freshman, where she cheered at Michael’s football games. She was even elected captain of the upcoming sophomore squad. “Perfect in every way,” her older brother Mel Jr. said. “She made me look bad.”

Stocky, crew-cut Michael came from a decidedly more blue-collar family and was a little rougher around the edges, but to his friends and neighbors he was a real-life combination of James Dean and Wally Cleaver. “He was the brother I never had,” said neighbor Dee Hinton. “Everybody in the neighborhood loved him.” Michael liked girls, sports and cards, but had little interest in school. He played on the freshman football team but due to his poor grades he was ineligible for the JV team that coming fall. “Sports lazy,” his sister called him.

Initially Michael was somewhat ambivalent about Patty. When they first started dating, he continued to go out with his sister’s friend Lois Schuehler, knowing full well that Patty would be hurt if she ever found out. That June he went out with another girl named Jackie, but, as Lois told investigators, “it was just for kicks to see what he could get.” He eventually settled on Patty and that summer he gave her the onyx ring he had received from his grandmother as a confirmation gift years earlier. It was official—they were now going steady.

Patty, however, didn’t act like a girl going steady and seldom wore Michael’s ring. Her friend and neighbor Terry Hutchinson recounted a story where Patty took off the ring and placed it on the radio. Michael saw it and put it in his pocket. “Where’s my ring?” he asked Patty. “It’s on the radio,” she said. “No, it’s in my pocket, Patty.” He gave her the ring back and she dutifully slipped it on. The incident apparently flustered Patty, but as far as Michael was concerned if she wanted his ring, she had to wear it all of the time. As Lois said, “he just didn’t care if her feelings got hurt, or if she was mad or not.”

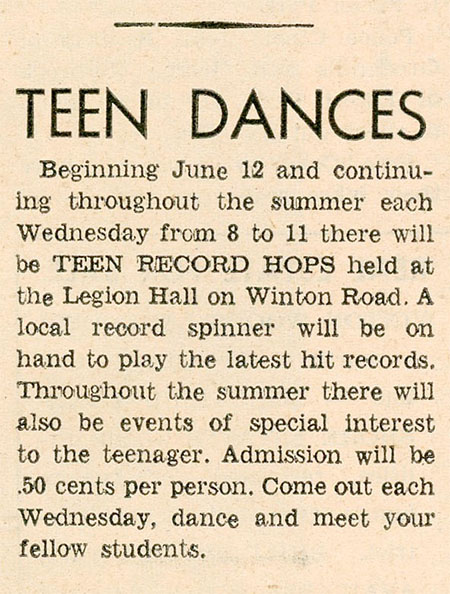

Lois wasn’t the only one to notice how Michael treated Patty. Michael’s best friend Ray St. Clair, who admitted that Michael had something of a temper, said, “He was a mean boyfriend. Whenever Mike took Pat out he tried to belittle her and would usually embarrass her in front of other kids.” The couple began bickering about small, petty things and Michael, more often than not, reduced Patty to tears, dismissing her reaction as just being a “baby.” Michael complained about her smoking (he smoked but didn’t think she should). Patty chided him on his poor grades (he failed two classes his freshman year and was making up one in summer school). Michael didn’t like going on double dates with her friends. Patty didn’t care for many of his friends at all. Perhaps their most serious disagreements, however, were about the weekly teen dances sponsored by the local American Legion post. Patty loved going to the dances and hanging out with her friends. Michael, who claimed he couldn’t dance and didn’t especially like the kids who went, didn’t want her going and flirting with other boys.

After one of the dances in July, Patty went with 16-year old Tom Stonefield to the Parkmoor Restaurant, a drive-in complete with roller-skating carhops, and they kissed in the back seat of the car. “It wasn’t a fleeting kiss, either,” Tom later said. The next morning, she called Michael and tearfully confessed her indiscretion while he silently listened. “Say something,” she begged. After a long pause he told her “there’s nothing to say.” She offered him his ring back, but he refused. Patty’s best friend, 14-year old Beth Upton, said they made up and appeared “lovey-dovey,” but Patty’s cousin later said that Michael was so angry over the incident that he hit her. This was apparently the last straw for Patty. She had had enough of Michael and by the end of the summer it was now no secret among her friends that she was interested in Tom, who had asked her to go steady with him that night in the car. She confided in her friend and teammate Diane Fisher that she was going to break up with Michael the next time she saw him.

Thursday, August 8th, 1963—the last day of Patty’s life—began as typical busy summer day. Patty arrived at cheerleading practice at 10:30 am. Afterward she walked to the drug store at the shopping center, met her father, Mel, and went home for lunch. That afternoon her older brother Mel Jr., who had his own car and spent much of his last summer before college ferrying Patty and her friends around, drove her to her friend Janet’s house where they admired Patty’s new puppy. Around 5:30 pm her father picked her up after work and they went home for dinner. That evening, around 7:30 pm, Mel Sr. dropped her off at Beth’s house on his way to a school board meeting.

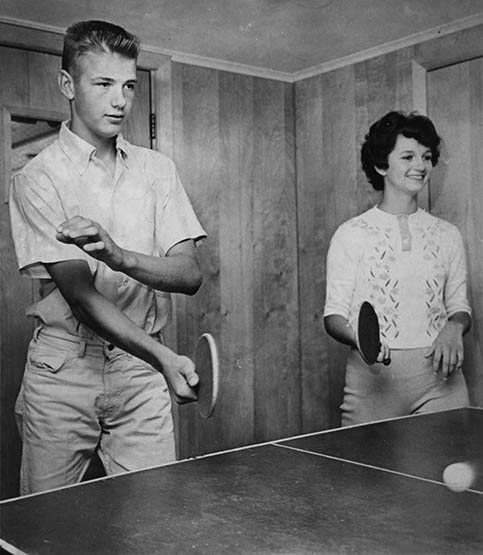

Sometime shortly after 7:00 pm Michael left his house and drove to the stables a few miles south on Winton Road to pick up his sister Cheryl who, along with Ray (who was not only Michael’s best friend, but Cheryl’s boyfriend), was riding Ray’s horse. Cheryl, who had a driver’s license, then drove them to their grandfather’s tavern in Corryville to pick up a keg of beer for their family rec room. “My dad didn't want to mess with the bottles,” Michael said. Michael arrived back home around 8:30 pm and he invited his friends over for a ping-pong tournament in the basement. Around the time Michael was beginning his tournament, Patty, Beth and several of their friends arrived at the weekly dance.

The turnout at the Legion Hall that night—on a Thursday that week instead of Wednesday—was larger than usual. Margaret Boyle, who was collecting the 50-cent admission at the door, counted more than 100 kids, including plenty from outside Greenhills she didn’t recognize. It was even rumored that some boys from the West End were there. “A rougher crowd,” said sophomore Craig Hatfield. Although Michael’s ring wasn’t on her finger but tucked in the bottom of her purse, no one recalled Patty dancing or even talking with any of the boys that night. As Beth said to an investigator, most of the boys were just standing around so the girls danced to the fast songs among themselves. They soon became bored and after only an hour they made plans to go to the Frisch’s down in the valley, then back to Beth’s boyfriends house to jump on his trampoline. Patty, however, decided to go see Michael.

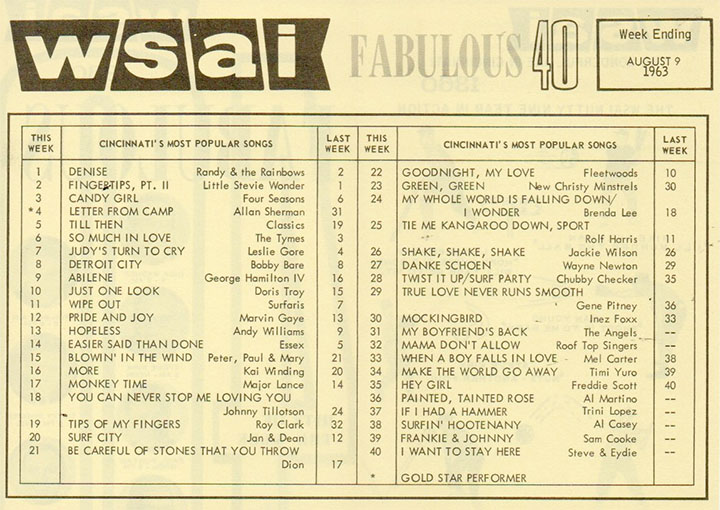

Compare with that week's Billboard Hot 100.

Around 9:20 pm Patty called Michael’s house from the pay phone at the Legion Hall, but he was busy in the basement drinking beer from a Dixie Cup and finishing his ping-pong game. “Well I can’t call back because this is my last dime,” she said, so Cheryl relayed her message to Michael, and he said it was OK if she came over. Patty told Beth that she was disappointed that she couldn’t speak directly with Michael but, nevertheless, left the dance for his house after the call. She didn’t tell Beth why she was going to Michael’s this late, but the only time she had ever done this before was to discuss a problem and apparently tonight would be no different; she intended to break up with Michael in person. She gave her cigarettes to her friend Sue for safekeeping then left the dance at 9:30 pm. Several of her friends and at least one adult chaperone saw her leaving alone.

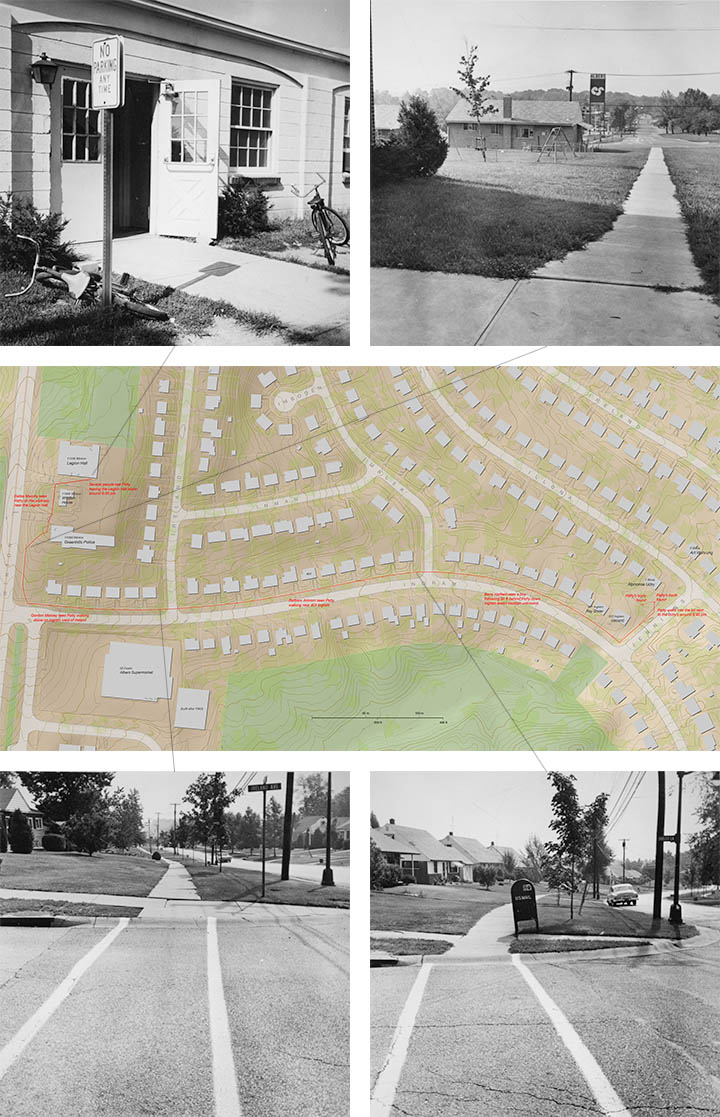

After she left the Legion Hall Patty walked a short distance down Winton and turned left onto Ingram Road. She then walked down the hill on Ingram and at the bottom turned left onto Jennings, a short 300-foot street which ended at the intersection of Japonica and Illona, just one house away from Michael’s. In all it was a half-mile walk that shouldn’t have taken more than ten or so minutes.

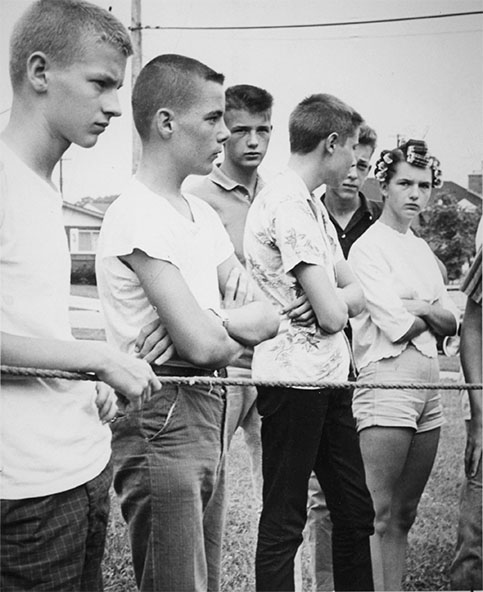

Cincinnati Post photos, August 13th, 1963

Several people later reported seeing Patty on her way to Michael’s. Gordon Massey, age 30, was driving to work and told police that he saw Patty walking alone and swinging her purse at the top of Ingram above Ireland Road. Barbara Ankrom told investigators that she saw Patty walking by herself on Ingram near her house between Ireland and Imbler.

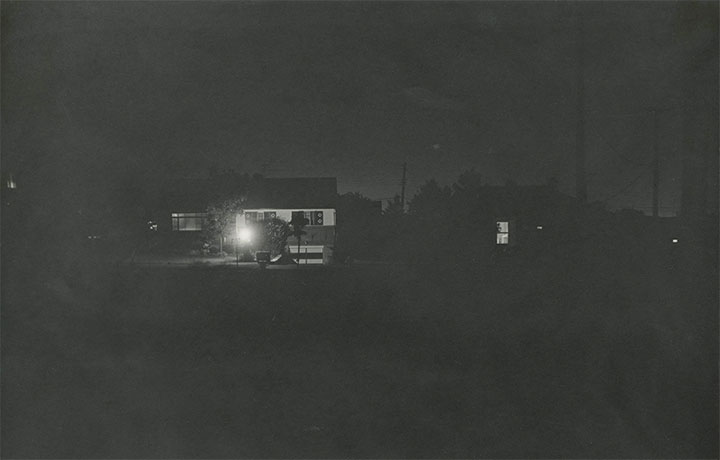

The moon was nearly full that night, but once Patty turned onto Jennings the only thing she could make out in the darkness was the distant gaslight in Michael’s front yard. It was likely the last thing she ever saw.

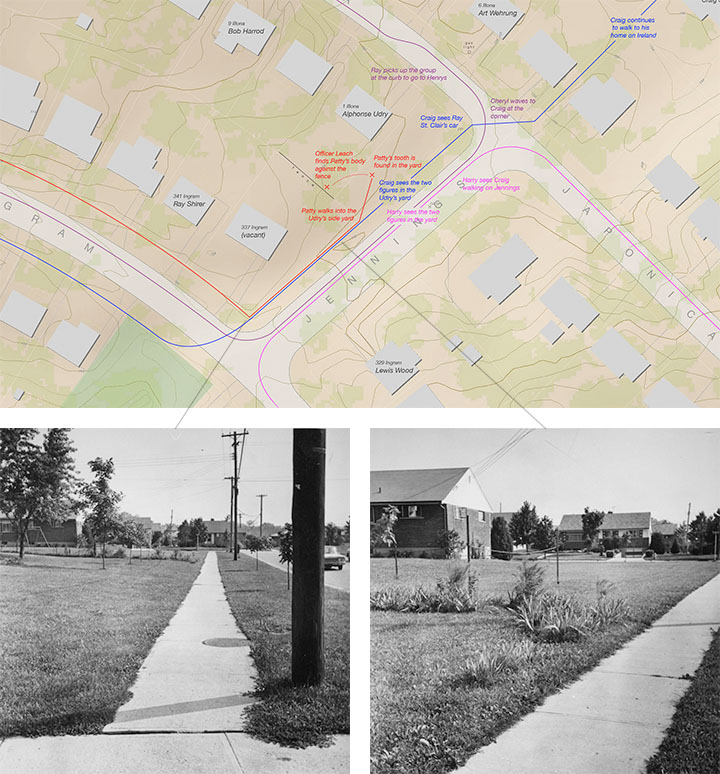

Around 9:35 pm 15-year old Craig Smith, who was filling in that evening for his friend as a clean-up boy at a doctor’s office in the shopping center, followed the same path down Ingram that Patty had taken only minutes earlier. He told the police that he saw two people in the Udry’s side yard—one lying down and another kneeling—but he couldn’t identify either of them. “I should have been wearing glasses in high school, but didn’t,” he told me. “My batting average dropped way off because of my vision, and the two figures I saw were just as indistinct as a curve ball.” He thought he had perhaps interrupted some kids making out and continued to walk to his home a block away. At the corner he said he was cut off by Ray’s car as it turned onto Jennings. The group in the car recognized him and someone even waved.

61-year old Harry Eckstein and his wife were returning home after visiting their son in nearby Brentwood. As he was driving down Japonica and turned his car onto Jennings, he saw two people in the Udry’s side yard: one straddling another on the ground as if in a “conquering position.” He thought something was amiss and slowed his car but after noticing Craig casually walking by, he assumed it was just some kids playing and continued to drive to his home on Ingram. He was certain the one on top was wearing a light-colored shirt and dark pants but told the police that “If I had any idea that the person lying on the ground was a girl I would have quickly investigated because I am positive the one on the top was a boy and that picture just don’t go together.” He estimated the time to be around 9:45 pm.

Cincinnati Post photos, August 13th, 1963

Around 9:50 pm Ray, Cheryl and Michael’s friends from the ping-pong game, Steve Tillett and Dale Boyd, left the Wehrung house in Ray’s red Chevy Nova to pick up hamburgers from Henrys in Finneytown, a 4.5-mile drive south on Winton. Cheryl even picked up an extra hamburger for Patty. Michael stayed home with his parents and younger sister waiting for his girlfriend to arrive. When Cheryl and Ray returned around 10:45 pm Michael was in the living room watching television with his mother. Patty had never shown up. Assuming her brother had picked her up after the dance everyone went downstairs to play cards. Ray later told police that is was then he first noticed Michael wiping off blood from a fresh cut on his wrist.

Mel Jr., however, hadn’t picked up his sister. He was patiently waiting at the shopping center for her. It wasn’t like Patty to be late and when she didn’t show by midnight, he drove home in a panic to wake his father. Patty’s parents began desperately calling her friends for any information; Beth told them Patty left the dance for Mike’s and Michael told them she never arrived. “[Patty’s mom] then started crying,” Michael said. Mel Sr. then met with officer Leach and reported his daughter missing. Mel Jr. soon showed up and enlisted Michael and Ray to help him search for Patty. They met officer Leach and on his instructions the boys traced a path from the Legion Hall, via the crosswalks between houses, to Michael’s house. It was precisely the route that Patty didn’t take that night. But after only 20 minutes of searching Michael begged off, claiming that his mother wanted him home. “Mike didn’t seem too concerned,” Mel Jr. later said. “He was very quiet.” Mel Jr. reported their findings to Leach and, after he spoke with Mr. Rebholz, a county-wide all-points bulletin was broadcast at 2:30 am, August 9th (Female, White, 15, 5'4" 115#, Blond hair and blue eyes. Last seen at…).

Mel Jr. spent the rest of the night canvassing the streets around the Legion Hall searching in vain for his little sister.

Leach, who had spent much of the night coordinating the missing persons report, finally resumed his regular patrol and found Patty in the Udry’s yard in the hour before dawn. She was only 25 feet away from where Craig Smith and Harry Eckstein had seen the figures the night before. Mel Sr., after what was no doubt a sleepless night, was notified by a county detective and soon arrived at the scene. The police, hoping to spare him the sight of his daughter’s bludgeoned body, tried to have him identify her from the contents of her handbag (54 cents in a red coin purse, several pieces of costume jewelry, various scraps of paper, a bottle of Midol and Michael’s ring that she never had the chance to give back). When he couldn’t they pulled back the wool blanket covering her body. 15-year old Carolyn Udry, who was asleep just 50 feet away, said she was awakened by her German Shepard, looked out her bedroom window at the commotion and saw Mel Sr. beating on the hood of a police cruiser shouting “No, no, no!” By daybreak the quiet corner lot had become an active crime scene. By that afternoon it was overrun by newspaper reporters and TV crews. By that weekend lines of cars—nearly 2000 that Sunday alone, some from as far away as Indiana and Michigan—were filing past the crime scene.

Patty’s body was found. Michael’s house is right of center behind the telephone pole.

Note the 1962 Pontiac Tempest in the foreground. ~12:30 pm, August 26th, 1963. GHPD

Mel Sr. drove home to break the news to his family. “He walked in the house, probably about six in the morning, and said she was dead,” Mel Jr. recalled, “At that point we just went crazy.”

II.

In March 1963, Greenhills, one of three “utopian” greenbelt towns built during the Depression by Roosevelt’s Resettlement Administration, celebrated its 25th anniversary. By then the city had become the picture postcard of white, privileged, middle-class suburbia; a close-knit, insular bedroom community of 5000 where everyone knew their neighbor and their neighbor’s business. It was seen as a safe place to raise a family and a refuge from the crime of urban Cincinnati. The five-man police department spent most of their time writing traffic tickets and issuing dog-at-large citations. That summer they were investigating a rash of bicycle thefts from the community swimming pool and the burglary of a vending machine truck. There had never been a murder in Greenhills before and Patty’s death caught both the police and local officials completely unprepared. As county prosecutor Ray Shannon later said they were soon in way over their heads.

The news of Patty’s death spread like wildfire. “My alarm clock that morning was my sister Cindy [Patty’s teammate] screaming,” said Craig Smith. “My mom came into my bedroom and said she had terrible news,” said another classmate. The story was reported on the radio, then on TV, and by that afternoon all of Cincinnati was aware of Patty’s murder. “Everybody was just really shaken up by it. It was just out of the blue,” recalled neighbor and reporter Bob Harrod. Almost any Cincinnatian of a certain age can still remember when and where they first heard the story.

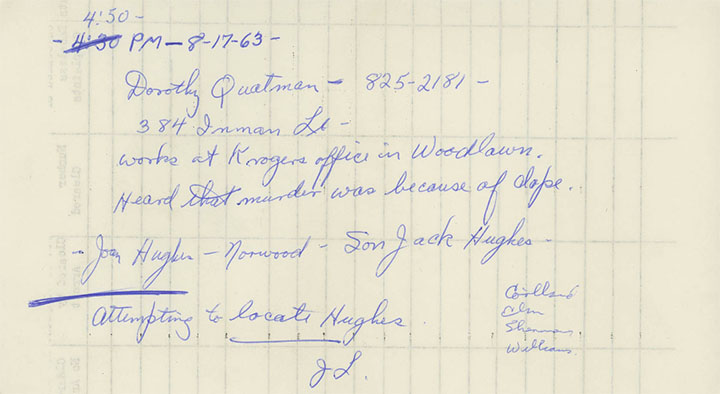

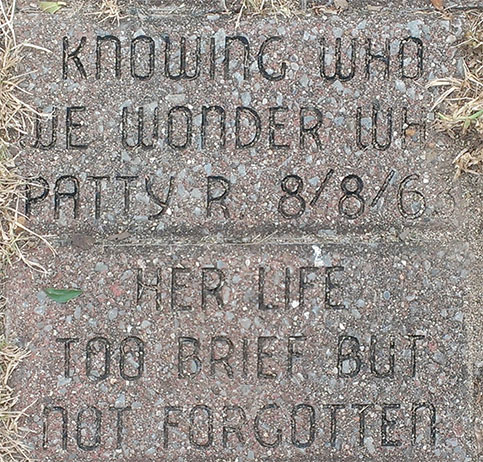

Note the Henry Wadsworth Longfellow quote

By that afternoon the Greenhills police department was deluged with more rumors and tips than it could possibly handle: Patty was killed because she was pregnant or involved with drugs, Patty was killed by Michael’s father or patrolman Leach in a jealous fit, or Patty was killed by a mysterious handyman or a weird neighbor who handed out pencils instead of candy at Halloween. There were so many calls that eventually the mayor and a secretary from the local school board were pressed into service to help take and transcribe them all. “Were not geared for this sort of thing.” said chief Baldwin, “We can’t keep up with the paperwork.”

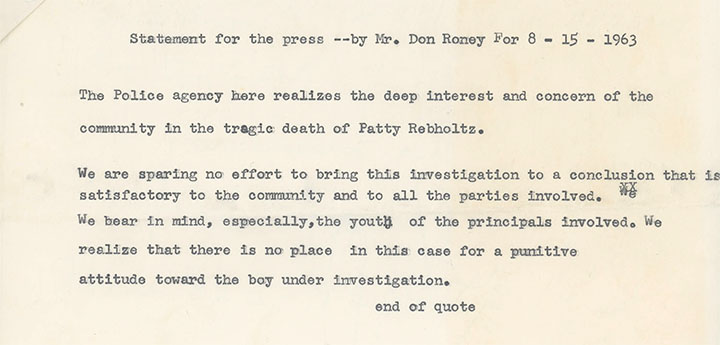

To quell the growing swirl of rumors and calm some of the fears, special investigator Donald Roney, from the Hamilton County prosecutor’s office, told a reporter over the weekend that “It was an unfortunate murder, not a madman’s,” and the community shouldn’t worry because Patty wasn’t the victim of a “maniac” or a “sexual deviant.” “I believe we will have an early solution.”

In fact, by this time Roney was quite sure he knew who killed Patty.

Assistant county prosecutor Donald Roney began his career in the prosecutor’s office on New Year’s Day in 1950. After his efforts in uncovering welfare fraud he became their chief investigator, working on nearly every major case over the next decade including several capital cases. Roney, a staunch Republican with political aspirations, had, even for that time, a particularly unnuanced, black-and-white view of crime and the criminal element. “It does little good to catch the offender then try to cure him. The crime has been committed,” he said in a 1960 newspaper article. “The 98% of law abiders have a right to expect that the other 2% will be kept in check.” His zeal for justice, however, occasionally caused problems: In 1956 he acted as the “bad cop” during the questioning of the meter reader Robert Lyons in the high-profile murder of the socialite Audrey Pugh. He lied about fingerprints lifted from the scene and told Lyons that he “was a cinch for the electric chair.” After a marathon 13-hour interrogation Lyons finally caved in and signed a lengthy confession. Lyons later recanted and his lawyer, the legendary Foss Hopkins, won him an acquittal at trial, largely because of Roney’s improper questioning. Later, in 1965, Roney abruptly resigned from the prosecutor’s office after they began investigating his role in the financial misconduct of the Ringgold Building and Loan Co. In a suprising reversal he, along with fellow assistant prosecutor Burton Singer (another Ringgold officer), became defense lawyers and within a week were representing their first client, Posteal Laskey, the infamous Cincinnati Strangler.

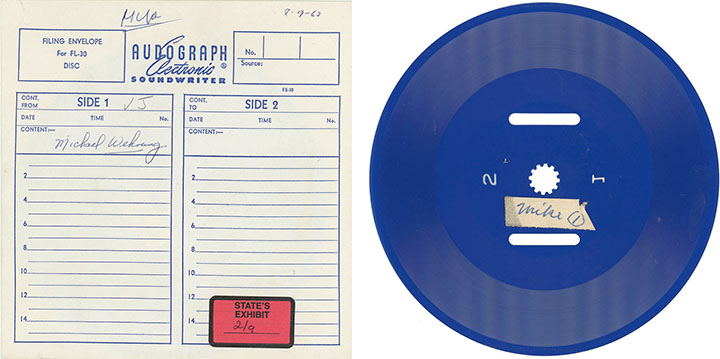

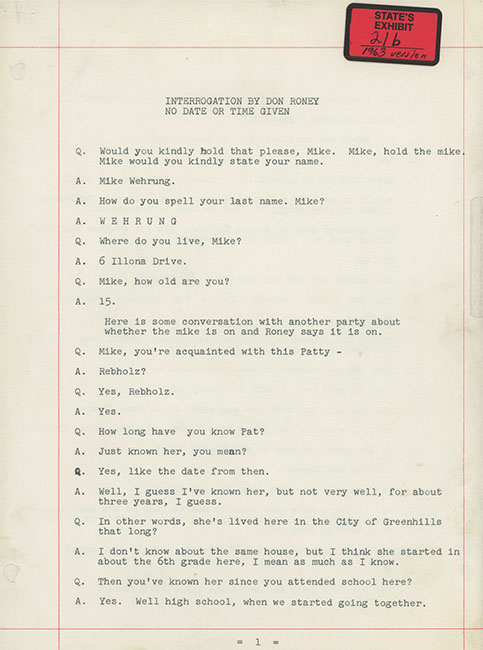

On the afternoon after Patty’s murder, however, criminal defense work was likely the furthest thing from Roney’s mind. After a long day of interviews, Roney sat across from Michael at the Greenhills Police station, turned on the Audograph Soundwriter, asked Michael to hold the microphone close and began his interrogation:

“Did you leave the house between 9:30 and 10 pm?”

“Oh, yes I forgot to tell you. I decided to—you know—to walk over down Jennings and see if I could see anything of her coming… so I cut across [the] Udry’s grass… so I walked over there and looked both ways and I didn’t see anything and I whistled, and you know, I didn’t hear anything so I figured her brother picked her up so I went back home.”

It was an offhand remark, but Michael had placed himself at the scene of the crime. The seasoned investigator zeroed in pressing him on his whereabouts that night, the fresh cut on his wrist, his unusual change of clothing and his relationship with Patty:

“How many arguments did you have in the course of the four months?”

“What do you mean by arguments? You mean small things?”

“Right.”

“I guess about 50 of ’em.”

“In other words the two of you weren’t too compatible. You didn’t really see eye-to-eye… Why go steady with someone you argue with?”

“We didn’t argue. Just small things.”

Michael was understandably nervous and Roney, somewhat disingenuously, tried to reassure him:

“You are just a young lad; you are just a boy, and there is nothing in the world that can happen to you because you’re just a boy. No matter what, if the very worst came to pass, nothing could happen to you because you’re a boy.”

“Ummmmmm”

“You have no reason to fear for your life.”

“I’m just shaky, I’m not really scared.”

“I know what you mean. No matter what—if you did it—still nothing could happen to you because you are only a boy.”

“Yes.”

“There’s no reason for you to be upset and shaky. We’re just trying to find out how the girl came to an end.”

By the end of the questioning Michael was so shaken he simply didn’t know what to say:

“At this time awhile ago you said you had on your striped zippered shirt, Levis and a pair of shoes. How did the shirt get down to the hamper with the Levis upstairs?”

“I don’t know. I don’t know what I’m talking about.”

“Mike, we’re in a very serious position here.”

“I know we are. You have me so confused I don’t know what I’m doing.”

The Warren Commission relied heavily on Audograph transcriptions in their investigation of

JFK’s assassination.

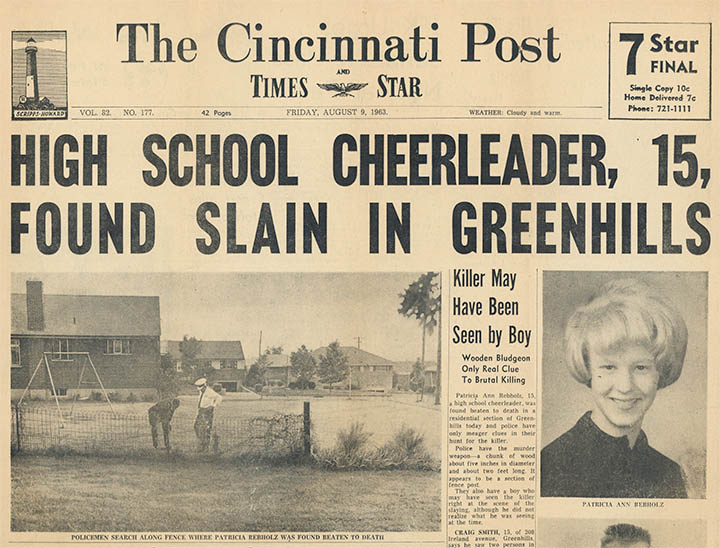

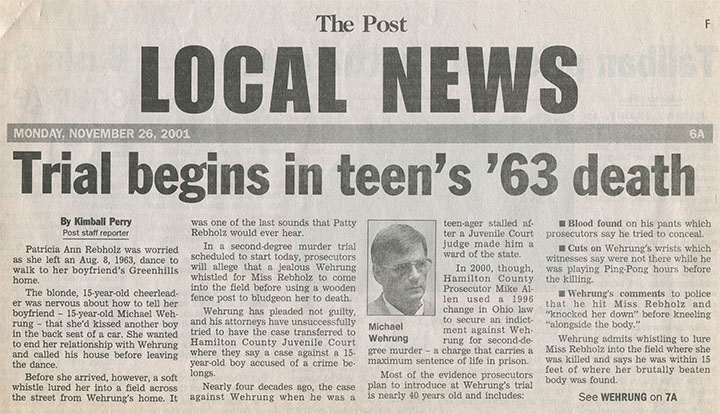

The murder of a pretty teenage cheerleader in a quiet Cincinnati suburb was a sensational story and even bumped the death of president Kennedy's premature son from the headline in that afternoon's Post. For the next several weeks Patty and Michael—especially Michael—were the headline in morning and afternoon papers and the lead story on TV and radio newscasts. Despite the fact that most of the subjects were just teenagers, jaded beat reporters had no problem publishing names, photographs and even addresses and phone numbers. One reporter was a neighbor, and another even befriended the Wehrungs and ultimately became a witness in the case. It was the most important story in Cincinnati that summer and the media frenzy was simply unprecedented.

The Post 7-Star Final was published in the afternoon for home delivery. It was the first newspaper

account of the murder. Nearly two full pages were devoted to the story

The Enquirer was published for morning delivery and this was their first account of the story.

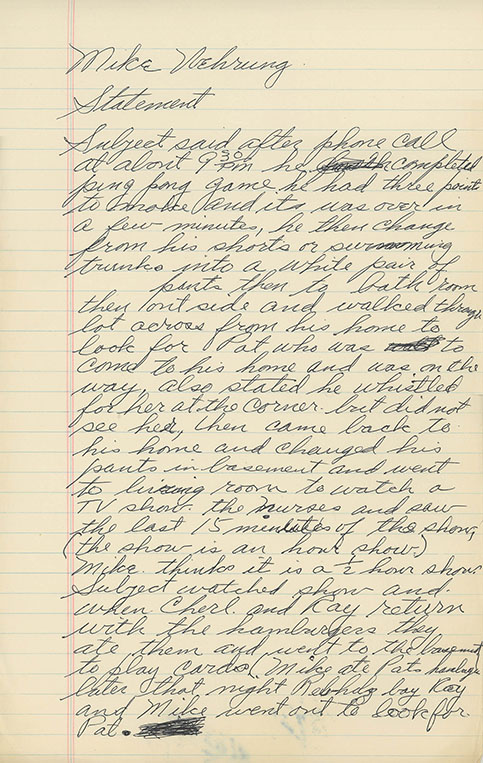

Meanwhile, Greenhills’ overwhelmed police force did what it could. They interviewed witnesses, sent Patty and Michael’s clothes to the crime lab and even, with the help of the coroner, made molds of the crime scene. To assist the beleaguered department, detective Chris Waldeck from the North College Hill police was assigned to the case. As part of his investigation he began compiling a series of undated, hand-written notes that portrayed Michael and his family in the worse possible light (“Subject was drunk the night before and was asked to leave a drive-in theater; Subject may have set fire to barns; Mother changed story about that night; the mothers argued about the murder on the phone.”).

Nearly 1500 mourners—mostly teenage girls—came to Patty’s visitation that Monday evening to pay their respects. Funeral director Clifford Hodopp said it was the largest crowd in all his years of operation. Almost two hundred attended her funeral the next morning but everyone’s attention was focused on Michael. An Enquirer reporter wrote “not once during [her] brief last rites did a sign of emotion touch his handsome face. And Mike’s flowers were there. A dozen red roses, standing on a little table near the casket.”

Several hours after the funeral Michael was escorted to the Norwood Police Station and hooked up to a Burns and Wilhelm Electric Psychometer for polygraph questioning. Gerald Lawson, the county sheriff’s former polygraph expert, was skeptical and told the Enquirer that the B&W device, which only measured fingertip responses, wasn’t even a real polygraph, but Roney replied that it was “one of the best machines in the area,” and he had complete confidence in it. The operator, Norwood Police captain Harry Schelie, questioned Michael for nearly six hours. Roney later told reporters that the results “were not disappointing.”

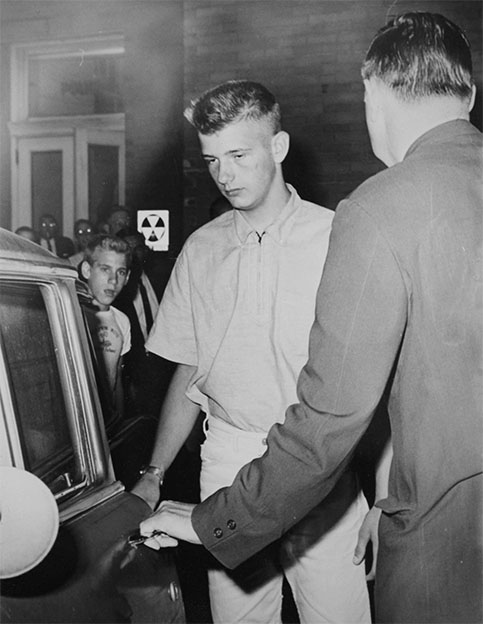

The next day, as a crowd of some 100 curious onlookers gathered at the Norwood station, Michael was again interrogated using the B&W Psychometer—this time for more than nine hours. During a break in the questioning Schelie and Michael were sitting around smoking cigarettes and talking about football. Michael said he wasn’t sure, but he thought he remembered kneeling next to Patty in the moonlight and could feel Smitty’s (Craig Smith’s) eyes “burning” into his. He thought that there was the possibility that he killed Patty, but it wasn’t his “real self,” because “the real me would never strike a girl.” He couldn’t help think, however, that his “other self” could have done it. He also told Schelie that he didn’t have to go over to the Udry’s yard that morning because in his mind he already knew who was on the stretcher. Whether this constituted a confession or were just the ramblings of a rattled, confused teenager remained to be seen, but afterward county prosecutor Raymond Shannon made no mention of it, saying only that Michael was “attempting deception.”

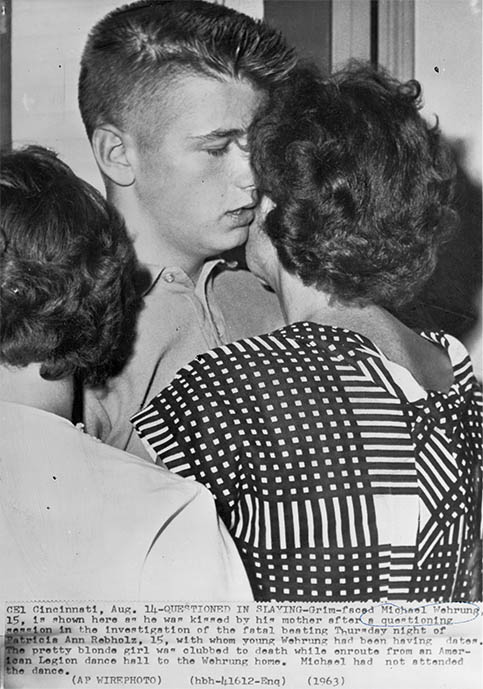

Cincinnati Post photo, August 14th, 1963

There is no record of all the time Michael spent in interrogation, but all of it was done several years before any Miranda rights and without the presence of a parent or lawyer. His mother told reporters that they didn’t think he needed a lawyer.

“Son, did you tell them the truth? Yes mom, I told them the truth but they won’t believe me”

That Wednesday the forensics tests came back. The blood spots below the knee on Michael’s pants were found to be type B—Patty’s blood type. Although there were no recoverable fingerprints on the log, the hair and bloodstains were both Patty’s. The case against Michael was quickly mounting: he couldn’t verify his whereabouts in the critical minutes around the time of the murder; he gave several different accounts of how he got the cut on his wrist; he couldn’t explain how Patty’s blood got on his pants and he never did produce the shirt he was wearing that night (and despite an extensive search, including the sewer system around his house, it was never recovered. One rumor was that his mother disposed of it on a trip to Indian Lake that weekend). “I know bloodstains don’t lie. I know the lie detector doesn’t lie. I know I don’t lie. I don’t understand it,” Michael told reporters.

Cincinnati Post photo, August 12th, 1963

are both already unhappy with the reporters’ camera. Cincinnati Post photo, August 12th, 1963

The non-stop media scrutiny and the relentless questioning of Michael eventually pushed the Wehrung family to the breaking point. “I don’t like this grilling. I don’t want the interrogations to go on endlessly.” said his father Art. “I’m tired of cooperating,” said his mother Dawn. “The press are taking pictures making Michael look like a criminal.” Roney said that during questioning every consideration was being shown for his well-being but others following the case disagreed. The local chapter of the ACLU sent a letter to the prosecutor expressing the “strongest possible exception to the procedures of Mr. Shannon’s office” and considered it “abusive and harmful to grill a 15-year old child over four consecutive days.” Furthermore, they wrote “If the crime remains unsolved the ruin of a young man’s reputation cannot then be mended by the tardy recognition of those in charge.” There was an almost overnight change in public sentiment and the backlash from the media caught Roney off-guard. He soon found himself defending charges that he was abusing Michael. A new investigator, Ernest Taylor, who was recalled early from his summer vacation, began working on the case. When asked if Roney had been removed from the investigation Shannon said, “He’s just been spelled off, he needed a rest.” Nevertheless, Roney never questioned Michael again.

The next week—the second week after Patty’s murder—the press began reporting that the case was “stymied.” Shannon replied that the investigation was continuing and entering a phase of routine police work, but behind the scenes the small team of investigators were working feverishly; Baldwin and Leach were logging 15 hour shifts every day. “It consumed us,” said Shannon. They were diligently preparing their evidence for the grand jury and hoped to bind Michael over to the court’s general division and charge him as an adult. Among those paying attention to these developments was judge Benjamin Schwartz.

Schwartz, who spent 17 years as a Hamilton County Juvenile Court judge, was never one to shy away from controversy. He believed in the traditional values of God and family and would often hand out medallions inscribed with the Lord’s Prayer. “90% of the youth appearing before me do not attend church or Sunday school regularly. This is not coincidental or accidental,” he wrote. His screed against the Beatles corrupting influence on teen girls after their 1964 Cincinnati appearance is now legendary. At the same time, he also modernized the court with new programs and services for the delinquent—everything from psychiatric counseling, to weekend traffic school, to job placement programs. To his detractors he was seen as too lenient, but to his defenders he was seen as a progressive child-rights activist who believed in rehabilitation and used his authority in innovative ways. “This is not a court of injunctions and damages and corporate suits,” he said in a 1971 profile. “This is a court devoted to human beings.”

At least in principle Schwartz believed in scientific aids, including voluntary polygraphs, to help in his court. “Imagine the terror, the anger, the hatred for society of an innocent boy behind bars because of human failure to determine the truth,” he wrote. He had given permission for Michael’s initial polygraph questioning but soon began to worry that they were coerced and Roney was gaslighting the 15-year old in order to extract a confession, like he had done with Lyons seven years earlier. He eventually became convinced that Roney’s “intense interrogation and lie detector tests would be illegal and contrary to law.”

On September 1st—the third week after Patty’s murder—Schwartz held a highly unusual Sunday evening court session where Michaels’s parents petitioned to make him a dependent of the court and allow Schwartz to act in parens patriae as his guardian. They cited the tremendous strain he was under and told reporters “We have complete confidence in our son, but under the existing circumstances we feel we are acting in his best interest and the best interest of all concerned.” In the middle of the night, under a shroud of secrecy, Michael was sent to the juvenile detention center. Although Schwartz was quick to point out to the press that Michael was received as dependent, not a delinquent, his only other public comment was that “further proceedings will be in accordance with the confidentiality required of a juvenile court.”

Two weeks later Michael, with judge Schwartz’s blessing, was put on a flight to North Carolina to become a cadet at the Carolina Military Academy, whose motto was Dieu Defendit Le Droit—God Defends the Righteous. Why this particular school was chosen—a school the Wehrung’s likely had never heard of and were no doubt hard-pressed to afford—is unclear (one rumor was that judge Schwartz and Col. Leslie Blankinship, the school’s founder and president, were somehow related and Schwartz received a kickback for sending boys there; another was Michael’s father and Blankinship, who were both Masons, worked out an arrangement). Whatever the reason, however, Michael began his new school year several hundred miles away from home as one of 28 sophomore cadets. He wasn’t the first or last troubled boy from Ohio sent to the Academy.

This turn of events stunned the investigators. As a ward of the court they were now prohibited from nearly any contact with Michael. Schwartz, hoping to insulate Michael from what he considered the heavy-handed tactics of the investigators and the relentless media coverage, had, for all intents and purposes, effectively shut down the investigation.

By this time the Rebholz’s had become certain of Michael’s guilt and Schwartz’s actions left the family bewildered. “After we put two and two together and started thinking about exactly what had happened, there was no doubt in our mind who had done it,” Mel, Jr. said. “We were never given any explanation why he wasn’t charged at the time, and basically it was kept pretty much a secret where he went. [Schwartz] really obstructed justice by doing something like that. I can’t explain or understand why he made that kind of decision. But we’ve all had to live with it.”

III.

The first week in September—the fourth week after Patty’s murder—another school year began in a brand new, modern building. There was no such thing as grief counseling at the time, so her classmates were left to try to make sense of Patty’s murder by themselves, but no one had any idea what happened to Michael and didn’t know what to think. Craig, who was in the news all summer, told me he was worried about being back with all his classmates, “I thought I would be in for it—but I wasn’t. Nothing was said or asked.” Then, at the end of November, the shock of Patty’s death was replaced by the shock of the Kennedy assassination.

Patty’s murder devastated both families. Art Wehrung died suddenly of pneumonia in early October. He was only 41. His doctor told the press that his death “was not in the least mysterious. He just picked up the germ somewhere and it got hold of him fast.” However, classmate Ken Faig, Jr. wrote, “My mother was one of many parents who told their children that, whatever his diagnosis, [he] died of a broken heart.” The Rebholz’s were devout Christian Scientists and could never reconcile their daughter’s death with their beliefs. They left Greenhills for Columbus, had another daughter and later divorced. “They basically lost their religion,” Mel Jr. said. “It was the saddest thing to see. Neither one ever fully recovered from that night.”

The man in the background was a minder from the sheriff’s department making sure Michael

didn't “accidentally” wander off.

Parents in Greenhills never had a reason to worry about their children’s safety before—the city didn’t even have a teen curfew—but after the murder that all changed. Mothers wouldn’t let their daughters out after dark or let their sons play in the woods. There was even talk of moving trick-or-treat to the afternoon that October. It was the day “people realized there’s evil out in the world,” said Mel Jr. “Nothing was ever the same after that morning. It took away my innocence and I never felt young or safe again,” said Carolyn Udry. The murder had subtly, but permanently, changed the community.

Michael spent two years at the Carolina Military Academy and was even a tight end on their junior varsity football team. After he was released from juvenile custody in 1965, he, against former mayor Lindner's wishes, decided to return to Greenhills High School for his senior year. While some of his classmates don't remember him returning, others, including a few of Patty's friends, said he poisoned their senior year.

That senior class—the Greenhills Class of ‘66—graduated and went on with their lives. They started jobs. They went to college and began careers. They fought in Vietnam. They married, divorced and remarried. They had children then grandchildren. In the years, then decades that followed, however, they never forgot about Patty; she was the topic when they met at the local post office or the grocery store or the class reunion. The death of their pretty, popular friend was tragic, but never bringing Patty’s killer to justice—never having closure—was the thing that stuck with them all those years.

After judge Schwartz declared Michael off-limits in 1963 the prosecutor returned the case to the Greenhills Police. The typewritten interviews, the police reports, the crime scene photographs, and the blood-stained clothing all sat languishing in cardboard bankers’ boxes in a basement property cage with an open lock that no one could remember the combination to. Although the GHPD were rather lax in their care and control of the evidence, the idea that they couldn’t close the case always bothered them. Larry Zettler, who graduated from Greenhills High School in 1961 and knew many of the kids involved in the original investigation, returned to the community as a patrolman in 1972. He looked through the files and wondered why Michael wasn’t charged in 1963. “They weren’t Sherlock Holmes, but there was certainly enough evidence even then,” he said. However, the small department never had the resources to continue the investigation and no other agency was interested. Over the next 30 years, as new police chiefs came and went, the case grew colder and colder. But then, in the 1990s, came a new forensic tool—DNA.

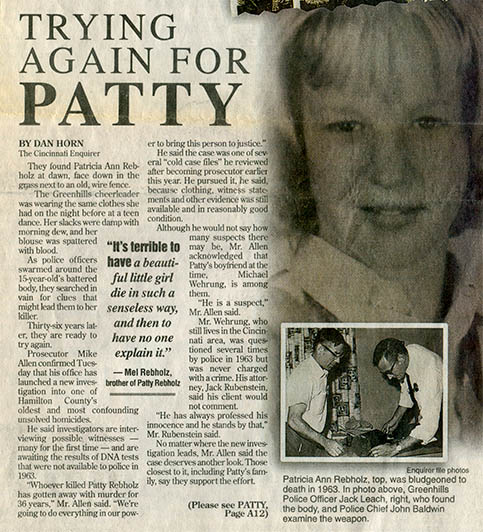

Initially DNA analysis of the physical evidence simply out of the reach of the department. “It cost something like three thousand dollars plus the cost of a technician from Maryland,” Zettler told me. But, in 1999, the Ohio Bureau of Criminal Investigation began offering free DNA testing to local police departments, so chief John Sellman sent some of the clothing to their state-of-the-art lab in London, Ohio. This caught the attention of Mike Allen, the new Hamilton County prosecutor.

Allen was a police officer, an assistant prosecutor, then a municipal court judge before he became Hamilton County’s Republican party chairman. After the county prosecutor Kenneth Blackwell was promoted to Ohio secretary of state in early 1999, Allen was appointed to replace him. Like his predecessor, he saw the position as a stepping-stone to a state office (“Governor,” said his wife unhesitatingly when asked). He hoped, at least in part, that the successful prosecution of Patty’s murder—one of the oldest unsolved murders in the county—would bring him statewide, perhaps even national attention, and in May 2000, the case did receive a national audience when CBS profiled Patty’s murder on 48 Hours.

The results from the BCI lab were inconclusive. The 35-year old evidence, deteriorated and water damaged by a flood, yielded nothing more than a fingerprint on Patty’s handbag (and that was traced back to one of the original investigators). Allen then sent the evidence to the Hamilton County Crime Lab, but they too couldn’t find any DNA. Despite the lack of any modern forensic evidence, Allen continued with his investigation. He assigned a lawyer and two investigators to the case and they spent months poring over the files, soon focusing on Michael as the only likely suspect. They had a service transcribe his recorded statements. They re-interviewed witnesses who were still alive and sent letters to Patty’s former classmates. They even sent a letter to the Roberson county newspaper in North Carolina, asking if any one remembered Michael when he attended school there.

By this time Michael was aware of Allen’s new investigation and tried, unlike in 1963, to retain council, but most local defense lawyers thought he had no chance against Allen and what they assumed was DNA evidence. They suggested that he strike a deal, but Michael was adamant—he was innocent and would not accept any kind of plea bargain. During the 1999 Christmas holidays he ended up hiring Earle Maiman, a lawyer from Thompson, Hine and Flory, the firm that represented Ray St. Clair Roofing, where Michael had worked for his childhood best friend for the last 16 years. Maiman was an accomplished civil litigator but had no previous criminal defense experience so long-time local defense attorney Jim Perry was added to the team. The pair turned out to be surprisingly effective advocates.

On May 2nd, 2000, a grand jury indicted Michael on second-degree murder charges and the case was assigned to the Hamilton County Common Pleas judge Patrick Dinkelacker. Maiman argued that it was unconstitutional to charge Michael as an adult because he was a juvenile at the time of the murder, but Dinkelacker invoked a relatively new state law that allowed for the adult prosecution of crimes unadjucated as a juvenile. Maiman appealed Dinklacker’s ruling all the way to the Ohio Supreme Court, but in a 5–2 decision they upheld the lower court. After 37 years, Michael Wehrung, now a 54-year old father of two and grandfather of four, would finally be tried for the murder of Patty Rebholz. Had he been convicted as a juvenile in 1963 he would have been remanded to the state until he was 21, but now he was facing the possibility of life in prison.

Allen was clear that he didn’t like how the case was originally handled, especially the actions of judge Schwartz. “He ordered the investigators to shut down. They had no choice,” said Allen. “Obviously, in the year 2000, I’m not bound by that.” Many, however, saw his prosecution as a personal vendetta. “I know what revenge is, but what would justice be now?” asked Richard Kuhlman, who studied the case in the 1990s and even wrote a play about it. It was “an attempt to rewrite history,” wrote David Wells in the Enquirer. Allen responded that there is no statute of limitations on murder for a reason. “The person who stole her life so many years ago has been able to proceed with his life, raising a family of his own and spending precious time with his loved ones. Patty never got that chance.”

On the Monday after Thanksgiving in 2001 the State v. Michael Wehrung began in judge Dinkelacker’s third-floor courtroom. Addressing the jury, Allen laid out his theory that on the night of Thursday, August 8th, 1963, Michael left his house, walked across the street and cut through the Udry’s side yard where he waited for Patty to show up after leaving the dance. When she finally arrived, he whistled and lured her into the yard. After she asked to break up with him, he went into a rage and bludgeoned her to death. Jealousy, suggested Allen, was the motive. The price she paid for trying to switch boyfriends was her life.

Michael couldn’t have killed Patty, countered Maiman. He was in his living room watching TV with his mother at the time and there has never been any physical evidence to suggest otherwise. His so-called “other-self” confession was nothing more than “psychobabble”—the words of a naive and foolish teenage boy. “If he had [actually] confessed they would have arrested him. They never did,” Maiman told the jury. “Justice needs proof of guilt and the prosecution hasn’t had it in 40 years. He was innocent in 1963, ladies and gentleman, and he’s innocent today.”

Former coroner Frank Cleveland presented a horrifically detailed account of the murder. According to his autopsy, Patty, sometime between 9:30–10:15 pm, was beaten in the face hard enough to break a tooth then choked into unconsciousness. She was then dragged by her heels some 25 feet to the property line where she was bludgeoned with the fence post so violently that it broke her ribs and drove her head into the ground, shattering her skull. She never had a chance to scream for help or defend herself. The graphic crime scene and autopsy photos left the jury visibly shaken. “I spent most of the time we were reviewing the photos and film trying to focus on a point between two clouds outside the window behind the television screen,” wrote one juror. “Every time the 60-something coroner we were watching in the films referred to Patty’s ‘panties,’ I felt like I wanted to scream.”

Allen and chief assistant prosecutor Mark Piepmeier next turned their attention to the timeline of that night. They contended that the case hinged on an 8 to 10-minute period between 9:30–10 pm where no one could verify Michael’s whereabouts. In a videotaped deposition Craig Smith, now an art professor in Denver, recalled walking down Jennings and seeing the two people in the Udry’s side yard, then the car full of teenagers at the corner, but like he stated in 1963, he couldn’t identify either of the figures. “I’ve often thought I could have just said what everyone wanted me to say and convicted a 15-year-old boy of murder, but I couldn’t lie,” he told me. Steve Tillett, testifying via videotape from Florida, was with Michael that night and later went with Cheryl and Ray to get hamburgers. He said as they were leaving, he saw Craig Smith at the corner of Jennings. When asked if he had seen Michael as they left, he said no, but Maiman produced one of his 1963 police interviews where he stated that he saw Michael in the house through the picture window as he was getting into the car. “Would you agree that what you said back in 1963 is probably more accurate than what you’re remembering today?” Maiman asked.

This point was critical: If Tillett had seen Michael in the house then saw Smith at the corner, who had just walked past the two figures in the yard, then Michael could have not been in the yard at the time. He could not have been the murderer. Allen, however, suggested that Tillett’s timeline was open to interpretation.

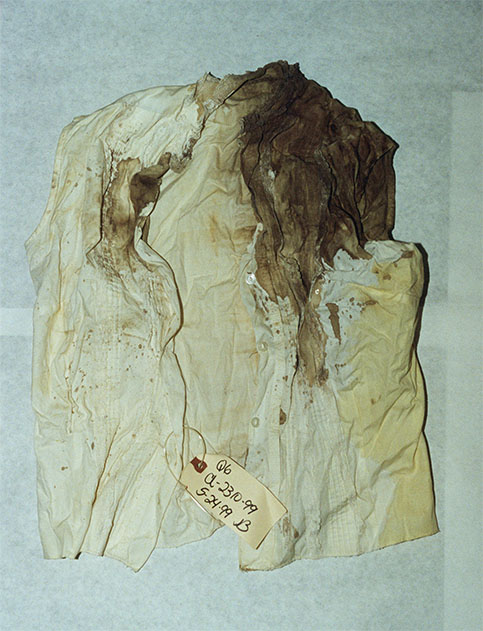

Joan Burke, a serologist from the coroner’s office, testified that there was no recoverable blood, either Michael’s or Patty’s, left on his pants and only Patty’s blood type left on her blouse and purse. Although the papers in 1963 widely reported that Patty’s blood was found on his pants, there was no official record of it the case file, and the judge ruled the old newspaper accounts inadmissible. As Maiman said in his opening, “There was no blood on Mike’s pants. There was no blood on Mike’s shirt. There was no blood on Mike’s shoes. None. Zero.” “But could there have been blood that had deteriorated over time?” Piepmeier asked over Maiman’s objections.

The original property tag reads “Was wearing pants when stated had wrist injury — Stated must

have wiped injury on pants”

In the shoe is the original property checklist

Despite the lack of physical evidence tying Michael to the murder, Allen and Piepmeier had established motive and opportunity. They now needed to introduce Michael’s confession—the so-called “other self” statement—and that came from their last witness, TV reporter Tom Schell.

Schell, who due to poor health was deposed in California a year before the trial began, was the lead reporter on the story in 1963 for Al Schottlekotte's Channel 9 News. He had befriended the Wehrungs and became a constant presence in their home, playing ping-pong and shooting hoops with Michael, and even shaving in their bathroom before going on air. “He was always around the neighborhood,” recalled Carolyn Udry. At one point Michael’s father asked Schell to talk to his son about his possible involvement in the murder. “He won’t talk to me. He won’t talk to his mother. He’s not going to tell his sister. He won’t talk to the cops. He likes you and if he’s going to tell anybody, he’ll tell you. Can you please do anything you can to get it out of him?” Schell then went downstairs and asked Michael about that night. Michael told him that he walked across the street and waited for Patty to show up. “Did you hit her?” Schell asked. “I slapped her,” Michael answered. “At that point I realized I was into this a heck of a lot deeper than I ought to be,” said Schell. He immediately notified the police and recalled that Michael told officer Waldeck he didn’t remember killing Patty but “It might have been another self.”

The prosecution called nearly 20 witnesses but in the end their case was almost entirely circumstantial; middle-age men and women trying to remember the specific events of a night nearly four decades ago.

Maiman’s defense was rather straightforward. Michael’s sister Cheryl, now Cheryl St. Clair, testified that the original investigators had questioned Michael for hours on end. She said that officer Leach “told me over and over that Mike had killed Patty and he’d buried the memory and I had to help him.” She even said that Leach had asked her to take Michael on a drive through the woods, rile him up and see if she could get him to confess. “What the police and media did [in 1963] was way out of control,” said Maiman. “They conspired to ruin his life.”

Maiman then presented his theory that there were other possible suspects the police never investigated. Barry Hatfield, then an 11-year old boy out playing hide-and-seek, testified that he saw a strange boy follow Patty down Ingram. “He wore taps on his shoes, had slick-backed hair and wore Buddy Holly glasses with chrome earpieces,” he said. “He never made eye contact with me and he seemed to be focused only on her.” Maiman argued that he could have been the killer but Piepmeier said it was simply the fevered imagination of young boy. Bonnie Davis, now Bonnie Armstrong, testified that she was walking down Ingram that night and 16-year old Robert Goodballet snuck up on her, frightening her so much she ran home. Maiman suggested this was another possible suspect. “He’s goofy, I agree,” countered Piepmeier. “But he’s a nice guy. He wouldn’t harm a mouse.”

Michael never took the stand in his own defense. Maiman hoped the lack of physical evidence and the alternate suspect testimony would be enough plant reasonable doubt into the minds of the jurors.

“I’m sure if the defense could have found other people who saw other individuals walking down the street that night, we would have had suspect 4, 5, and 6,” Piepmeier told the jury in his closing arguments. But the motive of Patty’s killer wasn’t rape or robbery: “Whoever killed Patty did so for no other reason than to end her life. Who would do this? Someone who snuck across the street to meet his sweetheart. Someone who instead of a kiss got a rejection. Someone who was told by his girlfriend, I don’t want to go out with you anymore.” “It was the person with the blood of Patty Rebholz on his pants. It was the person with the unexplainable fresh cut on his arm. It was the person who ultimately confessed to Tom Schell. [It was] Michael Wehrung.” In a final dramatic flourish, Piepmeier put on latex gloves, picked up the murder weapon—the fence post—and started pounding it on the courtroom floor, showing the jury exactly how it could have cut Michael’s wrist on that night in August 1963.

After seven days of testimony the case was turned over to the jury—seven women and five men—most in their 20s and 30s. In his instructions Dinkelacker said they had to follow 1963 sentencing guidelines; they could find Michael guilty or innocent of second-degree murder, but they couldn’t consider any lesser charge. It was either 20 years to life or nothing. The jury deliberated for 14 hours over two days, asking only to rehear the timeline testimony of Craig Smith and Steve Tillett. “If they had come to us and said you get to pick a couple of things you want to make sure the jury understands, those would have been the two I brought up,” Michael told a Cincinnati Magazine reporter. Initially the vote was split 9–3 innocent, but they all eventually agreed that too much time had passed and there was simply too much reasonable doubt. “It was the ‘CSI Effect,’” Zettler told me. “Juries just don’t want to convict without tangible scientific evidence.”

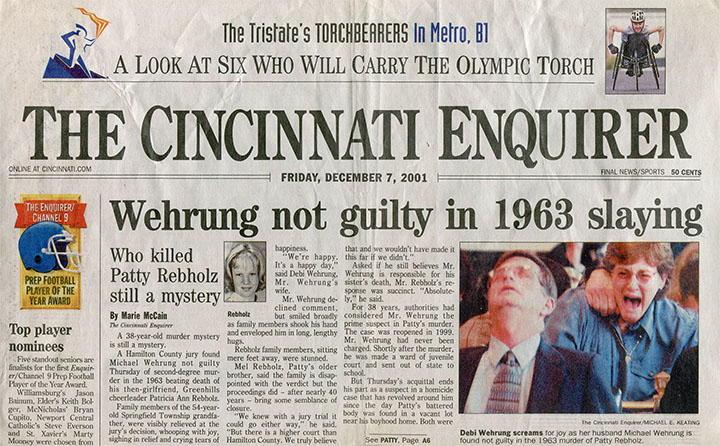

On the afternoon of December 6th, 2001, they returned their verdict. Michael Wehrung was not guilty of second degree murder.

While the Wehrung family erupted in a celebration of joy and relief, Mel Jr., who had flown in from his home in Florida to finally seek justice for his sister, slumped in his chair. After the verdict many of the jurors were openly weeping. “I feel for both families, but the evidence wasn’t there,” said one juror. “The sadness of it all was crushing,” said another. “Obviously, the ones who were crying were struggling with their decision,” a disappointed Allen told reporters.

Michael Keating’s photo was submitted for a Pulitzer Prize that year.

“We knew with a jury trial it could go either way,” Mel Jr. said after the verdict. “But there is a higher court than Hamilton County. We truly believe that, and we wouldn’t have made it this far if we didn’t.”

IV.

I was born eight months after the murder and spent my childhood growing up just two crosswalks away from the Udry’s corner lot. I followed Patty’s final route down Ingram every day for years; it was on my way home from grade school and the candy counter at the Variety Store or high school and the soda cooler at the Pony Keg. I walked past that yard hundreds, perhaps thousands of times. I don’t remember who first told me about the pretty cheerleader who was killed there—maybe it was my older brother or one of his friends—but as far back as I can recall I knew about Patty. To me and my friends—indeed, to several generations of Cincinnatians—she became a ghost story. “You know,” Greenhills Police chief Ferdelman told me when I visited the station, “some here think that Patty still haunts our basement.” Others are sure they have seen her haunting the auditorium of her old school.

But to the generation of kids in Greenhills before me—the first of the post-war Baby Boomers—Patty was never a ghost story at all. She was a daughter and sister, or a friend and classmate. She was the girl who went to cheer camp, band concerts, pool parties and drive-in movies, and her death was one of the defining moments of their childhoods; as Craig said, “The triangle of Patty’s murder, the Kennedy assassination, then the Beatles on Ed Sullivan are the profound memories of my teenage years.” Even today Patty’s friends thoughts on her death and the guilt or innocence of Michael still run surprisingly deep and personal.

It now seems unlikely that there will ever be a definitive answer to what happened to Patty in that yard that night more than a half-century ago and in another decade or so there will be few left to even ask the question: All of the original investigators are long since dead, Mel Jr. died of cancer several years after the trial, Michael is now a retired widower and Patty’s friends and classmates are now collecting Social Security. But Patty will never age. She’s forever frozen in time and space. She’s forever the teenage cheerleader in that dew-covered lawn at the corner of Jennings and Ilona.

—June 28th, 2016. Updated November 19th, 2019. Unclassified