132

A Cross-Section Anatomy

Eycleshymer, Schoemaker and Longacre

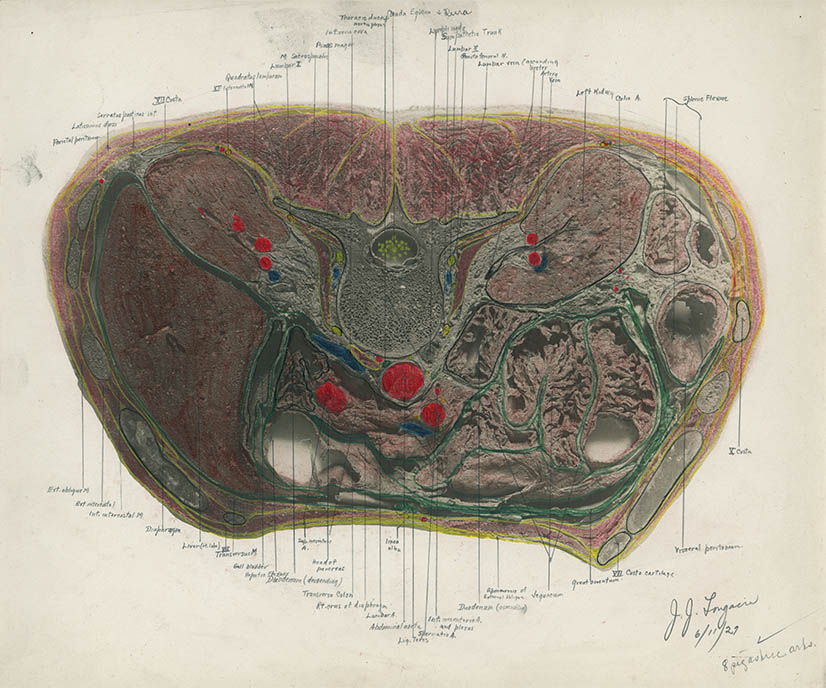

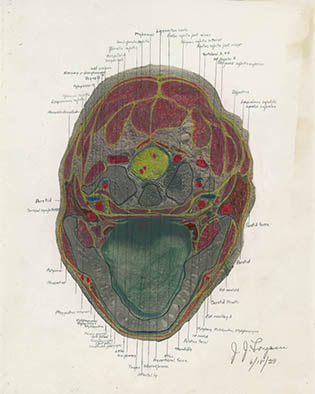

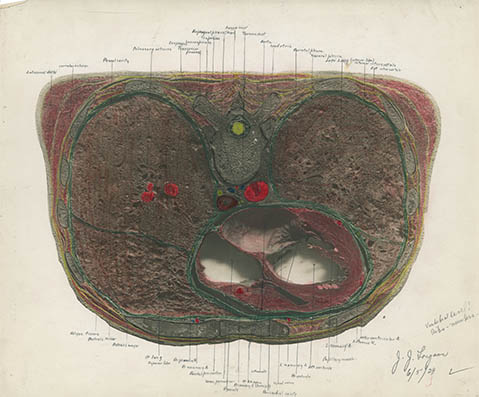

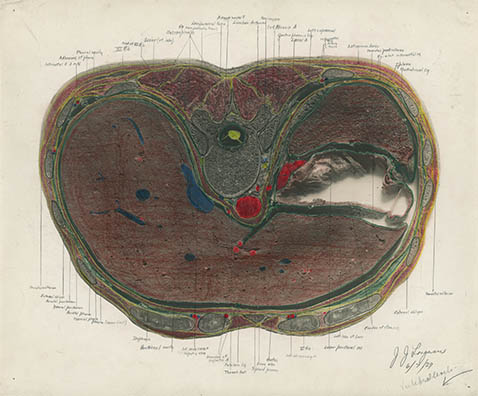

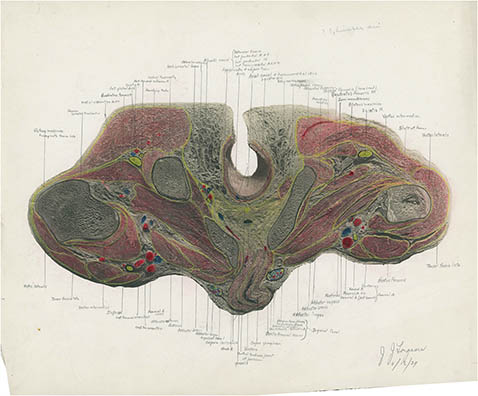

This hand-colored photographic print – labeled C25 on the verso – of a transverse section located at the L2 vertebra (roughly at the very bottom of the rib cage) was prepared by Jacob James Longacre on 11 Jun 1929 during his second year of Harvard Medical School for his Anatomy lab group. It was found among the papers tucked into his copy of Eycleshymer and Schoemaker’s seminal A Cross-Section Anatomy.

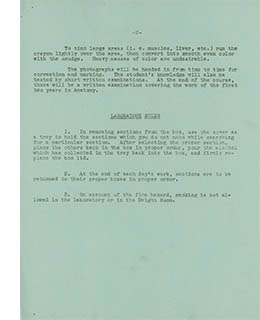

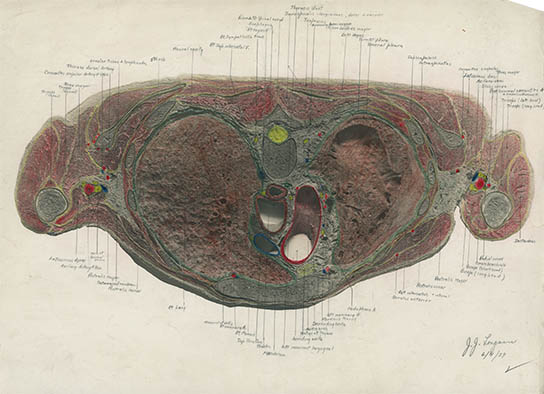

According to the 1930–31 syllabus, the Second Year Anatomy lab consisted of groups of four men studying a series of frozen sections.1 Each student was then responsable for coloring and labeling a blank B&W photograph of the section for the rest of the group. These annotated photographs were periodically checked and then presumably used by the group as a study aid for the written examination (which, it should be noted, covered both 1st and 2nd year anatomy). All-in-all not a bad way to teach a non-trivial subject:

“Preserve this copy, another cannot be obtained.” Indeed.

R3, uncompleted

Cross-sectional illustration dates back to the works of Leonardo and Vesalius, however, unlike typical anatomical specimens, the transverse cross-section required special preparation – initially this was by freezing.

As early as 1803, the anatomist Pieter de Riemer published specimens from bodies frozen in the Dutch winter.2 Forty years later the legendary Russian surgeon Nicholas Ivanovitch Pirogoff, with the advantage of presumably even more severe winters, developed a method “by which the human body could be so solidified by freezing and that it could cut like wood into thin sections,” and published the first great cross sectional anatomy – the five-volume Anatomie Topographica.3

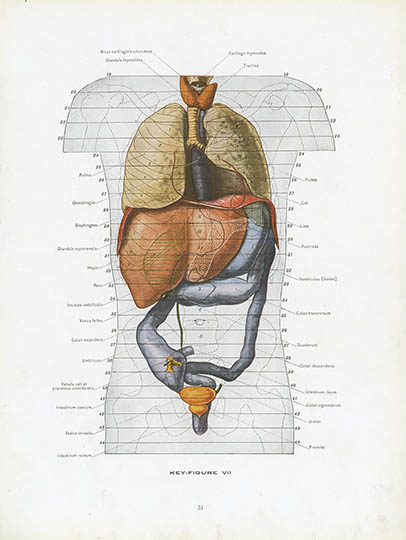

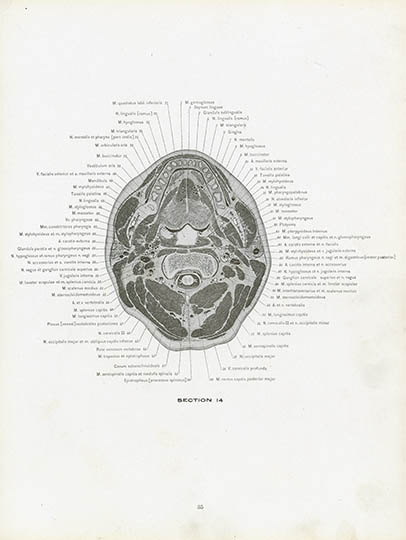

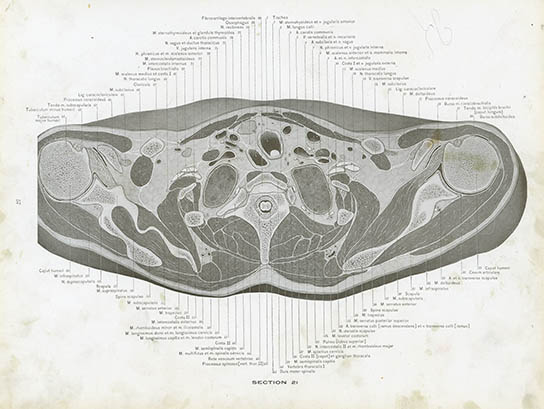

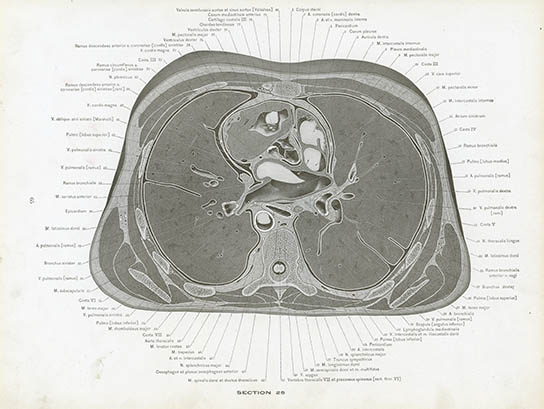

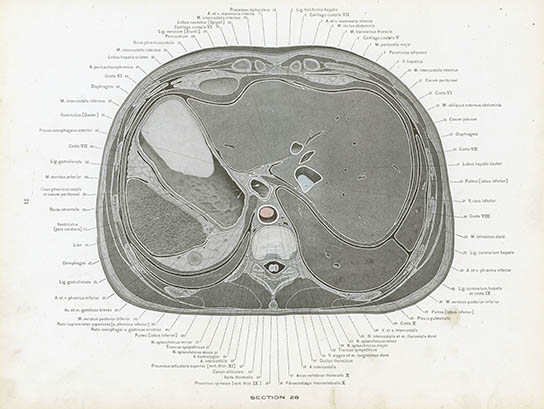

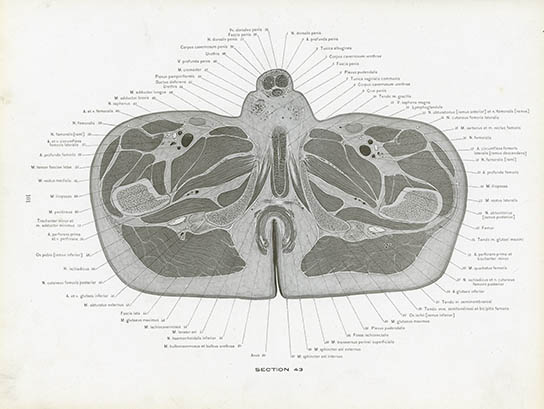

The next advance in tissue fixation was the use of formlin by Dimitrie Gerota in 1895.4 Using this method the St. Louis University anatomy professors Albert Chuancey Eycleshymer and Daniel Martin Schoemaker began to section subjects for classroom demonstration and research purposes. Eventually this lead to the idea of a comprehensive cross-sectional anatomy “to show the essential step between dissection and visualization; to suggest to the anatomist a basis for exact anatomy and to furninsh the clinician a gross anatomy in practical form.” It took the pair nearly six years – and sections from fifty cadavers – to publish A Cross-Section Anatomy.5

The key figures and illustrations – 113 in total – were done by the St. Louis University drawing instructor Tom Jones from glass-plate tracings. The quality of the meticulously labeled illustrations set a standard that no other cross-sectional atlas has matched, before or since. A century later, despite major advances in imaging and sectioning, Eycleshymer and Schoemaker ’s plates are still routinely referenced.

Here are a few of Longacre’s colored and annotated photographs and the corresponding E&S plates:

So what became of Jacob, our earnest med student? It turns out – thanks to some forensic Googling – quite a lot. He was born in Pennsylvania in 1907, graduated from Lehigh in 1928 and Harvard Medical School in 1932, then completed a general surgery residency at Cincinnati General Hospital. It was during this time that he met and married Margaret Suzanne Gruen, artist and heiress to the Gruen Watch fortune.

In 1942, while stationed in England as part of the 3d Auxiliary Surgical Group, he received further training in plastic surgery. After the War he returned to Cincinnati and built a sizable plastic and reconstructive surgery practice at the Christ, Childrens’ and Bethesda hospitals. Over the next 30 years he became a widely published, internationally recognized expert in, among other things, cleft-palate repair and bone grafts. He and Margaret both died in 1976.6

Bessie Hoover. Jacob Longacre, Margaret Gruen Longacre, ca.mid-1950s 7

1. Longacre’s class, HMS ’32, was entirely male. The first woman to apply to HMS was Harriot Hunt in 1847 and her application was, of course, summarily denied. The first woman accepted to HMS was Fe del Mundo in 1933 (and she had to live in an all-male dorm) but it wasn't until 1945 that an official class of women were admitted:

2003 was the first year that women applicants outnumbered men and, according to the HMS site, the most recent incoming class (HMS ’16) is 52% female. This timeline is rather representative of all US med schools.

2. De Riemer, Pieter. Exposition de la position exacte des parties internes du corps humain, tant par rapport à leur position mutuelle, que par leur contact aux parole des cavitiés ou eiles se trovent placées; avec une description explicative y relative. The Hague, 1818. No idea on the publisher, sorry.

3. Pirogoff, Nicholas. Anatomie Topographica, Sectionibus per corpus humanum congelatum, triplicl directione ductus illustrata. St. Petersburg: J. Trey, 1852–1859.

4. Gerota D. Ueber die anwendung die formois in der topographischen anatomie. Anatomischer Anzeiger, 1895;11: 417–420. If you are so inclined the entire volume is available at the Biodiversity Heritage Library.

IYI, formalin is an aqueous solution of methanal (CAS 50-0-0, AKA formaldehyde) with, typically, methanol added as a stabilizer and phosphate as a buffer.

5. Eycleshymer, Albert and Schoemaker, Daniel. A Cross-Section Anatomy. New York: D. Appleton & Company, 1911. The book was republished (with the original plates) in at least ten editions, the most recent being 1991. The plates here are scanned from Longacre’s heavily-used 1923 edition.

6. For more about his life see: Stark RB. Obituary. Jacob James Longacre, M.D., Ph.D. 1907–1976. Plast Reconstr Surg 1976;58(5): 657–9.

7. I know that were kinda running off the rails here, but bear with me for a second. Here is yet another portrait of Margaret – this time in 1935 as a 25-yo new bride:

The point of this note is that this portrait was painted by Maybelle Stamper, who would eventually teach print-making to some of your humble narrator's favorite artists – Charley and Edie Harper.

25 Nov 2012 ‧ Anatomicae