Charles B. Harper, the youngest child of Cecil and Ulma Harper, was born on 4 Aug 1922 in Frenchton, West Virginia and grew up on the 100-acre family farm. Roaming the Appalachian foothills as a child he gained a love of nature and an intense dislike of farm chores, so early on he decided to become an artist. After a year at nearby West Virginia Wesleyan College he realized he needed to attend a proper art school and enrolled at the Cincinnati Art Academy.

In his typical self-depreciating tone, he claimed that he picked the Art Academy based solely on the picture of the women upperclassmen on the cover of the brochure. After he arrived he found that these upperclassmen paid no attention to him. He did, however, meet another incoming freshmen – Edith McKee.

Edith Riley McKee was born 29 Mar 1922 in Kansas City and relocated to Cincinnati with her parents in the 1930s. An only child, she was a dreamer with a sharp artistic talent. After graduating from Wyoming High School, she, too, was accepted into the Art Academy. The two earnest teenagers soon realized they shared a common interest in, among other things, Miro and Klee. As Edie recalled many years later “We sat next to each other and liked each other pretty well.” Pretty well indeed – they would remain together for more than 60 years.1

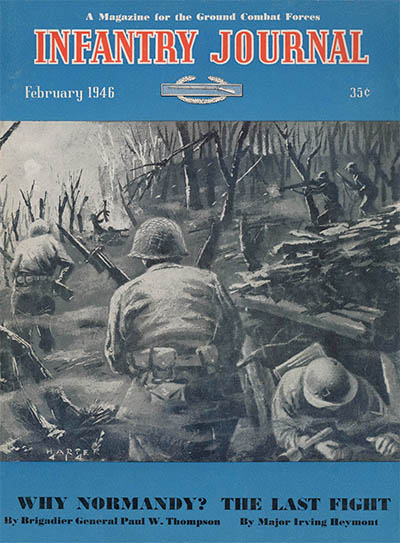

In Dec 1942 Charley was drafted and spent the rest of the war in Europe as a scout with the 104th Infantry. As he recalled in 1968:

“I see now that this was a fruitful training period for me as an artist (though I don’t recommend it as a substitute for art school) because it taught me to grasp the important elements of a scene quickly and put them down with a minimum of detail.” 2

Meanwhile, back home, Edie put her studies on hold to photograph for the Army Corp of Engineers. Although she described the assignment as “Dullsville,” her large-format work was good enough to win awards.

Attack on Eschweiler, Nov 1944, by the 414th Infantry. Charley’s first commission, Feb 1946

After the war Charley enrolled in the Art Students League and lasted one semester in New York. Licking his wounds, he returned to the Art Academy where he and Edie studied print-making with Maybelle Stamper and color theory with none other than the visiting Josef Albers. They both graduated in 1947 and he was awarded the first Stephen H. Wilder Traveling Scholarship.

Newlyweds, ca.1947

With Charley’s scholarship and Edie’s car, the newly-married couple spent six months on an extended honeymoon. They painted, sketched and photographed throughout the West and South. They even met Edward Weston and his cats in California.3 The trip inspired both of them throughout their careers.

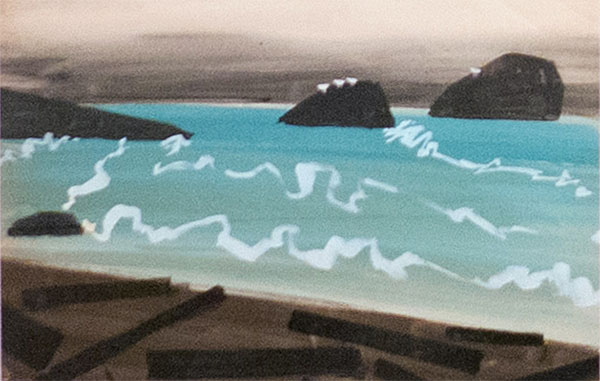

Honeymoon watercolors, 1947. Chris Glass

Returning home, they set up a joint studio in Edie’s father’s basement in Roselawn.4 Charley accepted a teaching position at the Art Academy as well as a job with the commercial studio C.H. Shaten.

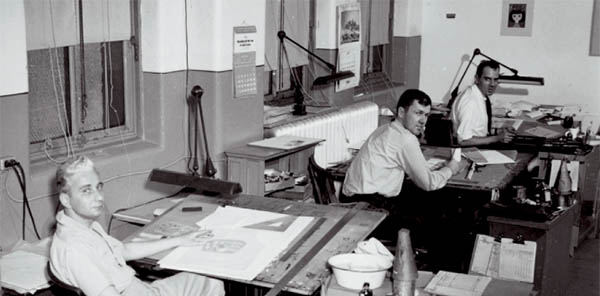

Charley (center) toiling away at C. H. Shaten, ca.1949. LPK

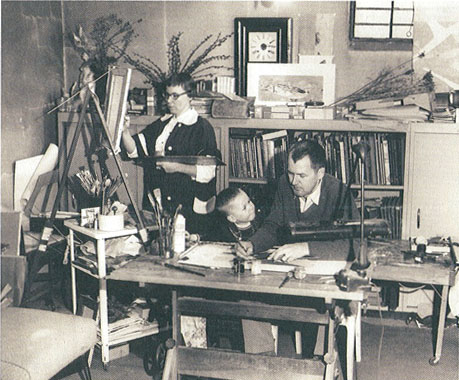

Edie, Charley and their son Brett in their Roselawn basement, ca.1956.

Commercial ad work proved difficult for Charley. He was frustrated illustrating the “happy housewife” and began to tire of realism altogether, stating that it “revealed nothing new about the subject, never challenged viewers to expand their awareness [and] denied me the freedom of editorializing.”

He began to experiment with a new style where perspective was replaced with hard-edged two-dimensional shapes reduced to only straight lines and curves and where shading and depth were replaced by overlapping color. To caricature and simplify at the same time. The idea was “...to push simplification as far as possible without losing identification.” He would eventually call it “minimal realism.” It was a style that would take him 30 years to perfect.

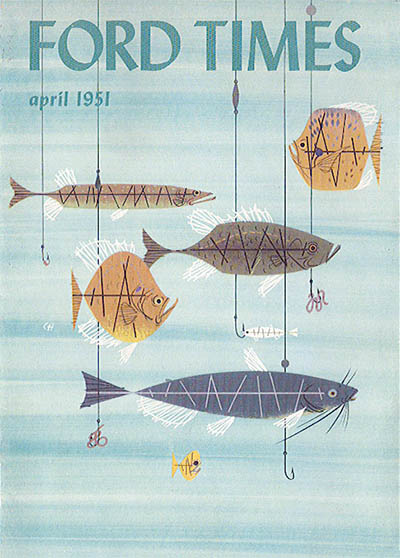

Cincinnati Pay Lakes, Charley’s first FT cover

The beginnings of Charley’s new style first appeared in the Dec 1948 recipe section of Ford Times magazine.5 This led to feature articles and finally cover illustrations. Over the years Arthur Lougee, the Ford Times art director and as close to a mentor as Charley ever had, gave him an extremely wide range of assignments – perhaps wider than any other Ford Times artist. Between 1948–1982 he contributed to more than 120 articles and illustrated more than 30 covers. Here are a few early examples:

Beating the Strings, Jun 1953. Glen Mullaly

Queen of Ramps, Apr 1955. Glen Mullaly

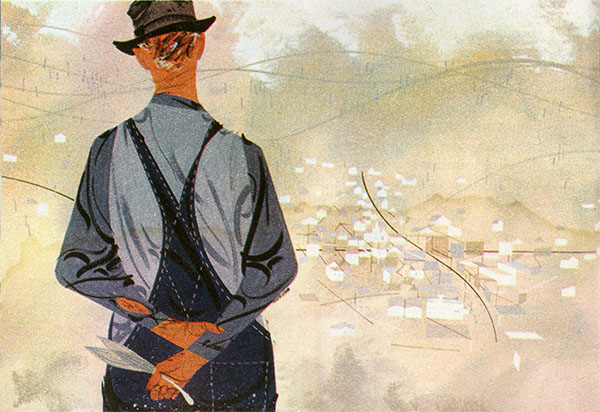

Hinton, Sep 1956. Glen Mullaly

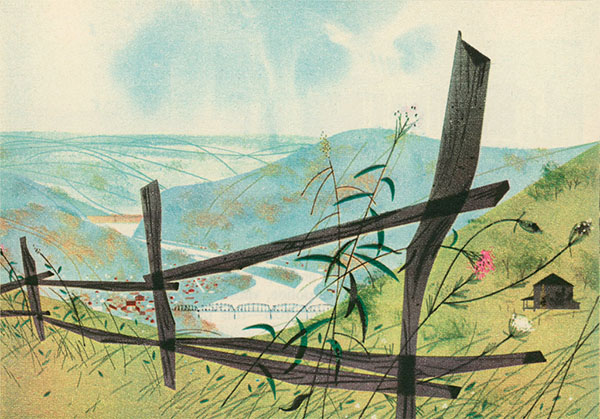

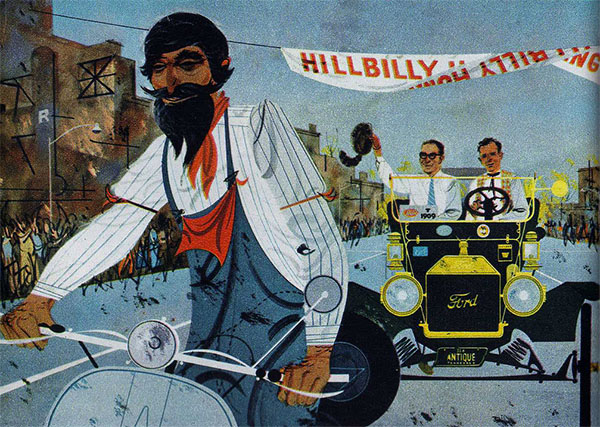

Hillbilly Homecoming, Jul 1958. DotDotCo

Fly a Kite with the Champion, Mar 1962. DotDotCo

Although less prolific than her husband, Edie also contributed illustrations to Ford Times:

Corner Cupboard, Nashville, Indiana, Apr 1953. Glen Mullaly

Tl;dr? Trust me, were just getting started...

1. For more about Edie see the studio’s official memorial statement: Edie Harper In Memoriam, or Horstman, Barry. “Edie Harper, artist, had whimsical, abstract style.” Cincinnati Enquirer. 25 Jan 2010 (online).

For more about Charley and Edie see: Bauer, Marilyn. “Cincinnati modernists reunited; An exhibit brings together visionaries, 50 years after their climb to the art world's summit.” Cincinnati Enquirer. 4 Aug 2002 (online), or Petit, Zachary. “Love Bugs.” A Line Magazine. 2011 Feb;1(10): 18–21. (online).

2. Quoted from: Harper, Charley. Letter to Hannah Wood, 1968 (online). The text of the letter became the artist bio that accompanied his Frame House Gallery serigraphs. We will certainly crib from this letter in later posts.

3. Edie, the photographer in the family, was so influenced by the Westons that she named her only son after Brett Weston.

4. 1403 Corvallis Ave.

5. Ford Times began in 1908 as a magazine for Ford’s dealer network and suspended publication in 1917. After WWII Henry Ford II restarted it as a consumer publication. Under the editors William Kennedy, Edmund Ware Smith and Nancy Kennedy (no relation), the magazine connected auto travel and sightseeing, outdoor sports, cooking, and a heavy dose of historical Americana to Ford cars. It was, by design, a combination of Reader’s Digest and Holiday, or as Ford stated, a “view of America through the windshield.”

In it’s heyday during the 1950s and 60s the small 64-page monthly reached a circulation of nearly two million – comparable to Time magazine. Ford outsourced the magazine in 1987 and ceased it’s publication in 1993. For a comprehensive scholarly overview of the magazine see: Swenson, Rebecca Dean. “Brand Journalism: A Cultural History of Consumers, Citizens, and Community in Ford Times.” (Diss. University of Minnesota, Mar 2012) (online).

For an analysis and checklist of Charley's contributions to Ford Times and Lincoln-Mercury Times see Terry Wright’s Ford Times Retrospective and Ford Times Finder.

Unless otherwise noted all images are copyright 2013 Estate of Charley Harper and are used here by permission.

11 Feb 2013, updated 27 Jul 2015 ‧ Illustration

A Charley Harper Retrospective:

I – Charley and Edie

II – The Birds

III – Tin Lizzie/Dinner for Two

IV – The Golden Book of Biology

V – Bambi and Childcraft

VI – The Animal Kingdom

VII – Frame House