93

Topographische Anatomie des Menschen

Eduard Pernkopf

Eduard Pernkopf was born 24 Nov 1888 in Rappottenstein, Austria. As a child he showed an interest in music but eventually followed in his late father’s footsteps and enrolled in the Medizinische Universität Wien where he was mentored by the noted anatomist Ferdinand Hochstetter.

After his graduation in 1912 he taught anatomy at several schools and in 1920 he rejoined Hochstetter in Vienna as an assistant and quickly rose through the academic ranks. It was while teaching gross anatomy that Pernkopf began to prepare dissection manuals which eventually attracted the attention of the medical publisher Urban & Schwarzenberg. In 1933 he signed a contract with U & S and began work on the monumental Topographische Anatomie des Menschen. The project would occupy him for the rest of his life.1

The superficial lymph nodes and veins of the face, lower head and neck

Right tympanic cavity viewed from above

Pernkopf worked tirelessly and maintained ridiculously rigorous standards for the project, He insisted that the artwork resemble living tissue and the 791 watercolor plates, mostly done by the Viennese artists Erich Leiper, Ludwig Schrott, Karl Endtresser and Franz Batke, are among the high points in the history of medical illustration. Beyond the artwork, however, the Anatomie’s presentation of regional stratigraphic anatomy is still unequalled. This was no introductory dissector for a first-year medical student but a reference for an experienced surgeon to study the night before a difficult case. It was perhaps the most complete, detailed and beautiful anatomy altas ever published.2

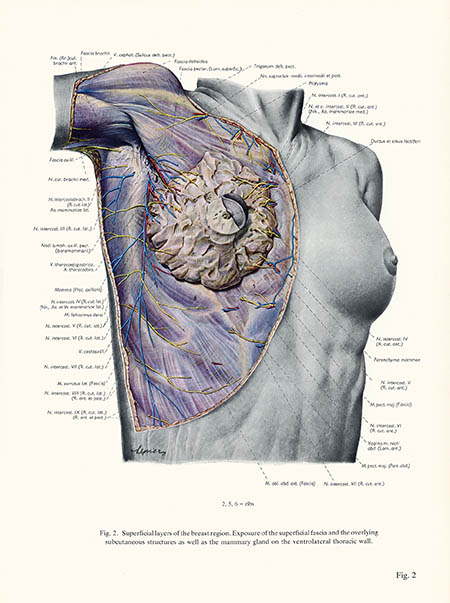

Superficial layers of the breast region

Blood vessels, nerves and muscles of the scapular region from behind

Of course there’s more to the story than this. Pernkopf was an avowed German Nationalist. In 1933 he joined the Nazi Party and the next year joined the Sturmabteilung. Shortly after Germany invaded Austria, Pernkopf was promoted to Dean of the Medical School and his first address was to support the ideas of Nazi racial hygiene by “furthering the propagation of the fit” and “eliminating the unfit and defective.” Within weeks he purged his faculty of Jews and other undesirables.3 In 1943 he became rektor magnificus of the University.

Although not specifically charged with war crimes, Pernkopf was imprisoned by the Allies in 1945. When he was released in 1948, stripped of all his titles and appointments, he returned to the Neurologie Institut where he spent the rest of his life working 18-hour days on the atlas. He died suddenly of a stroke on 17 Apr 1955. The final volume of Anatomie was completed by Werner Platzer.

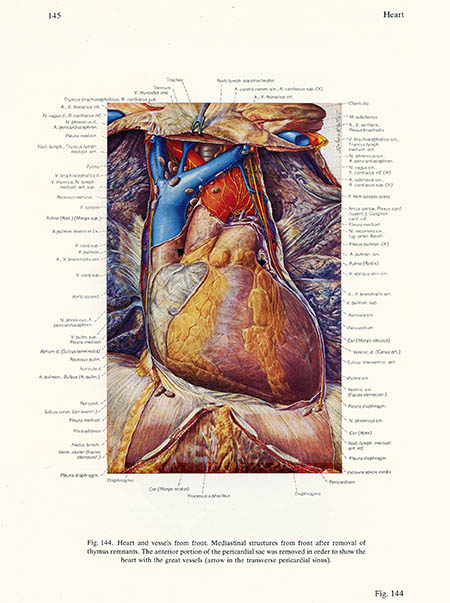

The heart and vessels from the front

In 1963 Helmut Ferner, director of the Anatomy Institute, University of Heidelberg, reorganized Pernkopf’s work into a two-volume atlas, Eduard Pernkopf, Atlas der topographischen und angewandten Anatomie des Menschen. It was translated into several languages and updated in 1980 and 1988.4

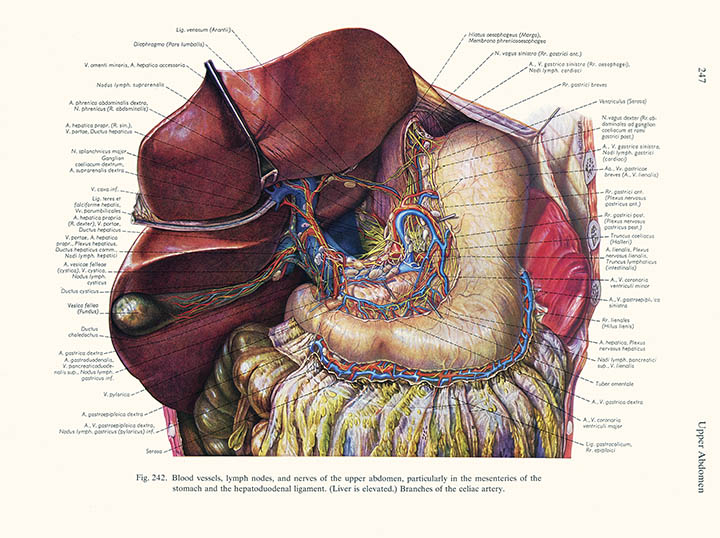

Blood vessels, lymph nodes and nerves of the upper abdomen

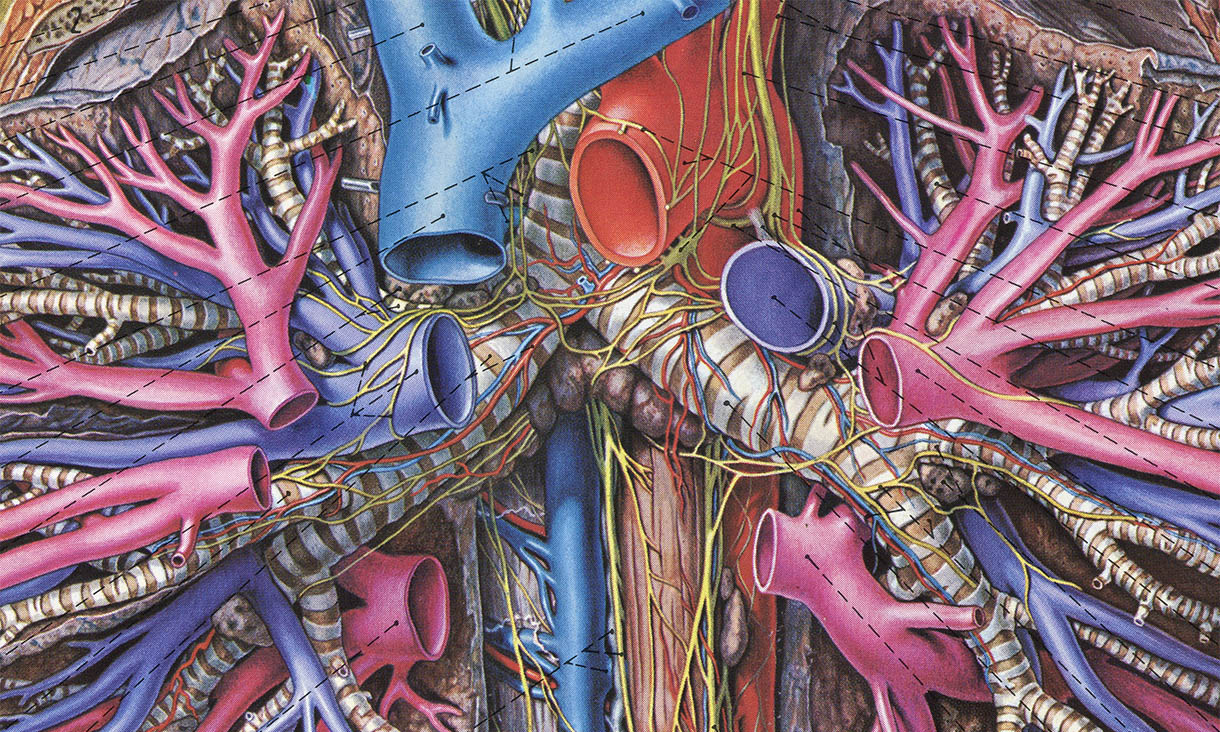

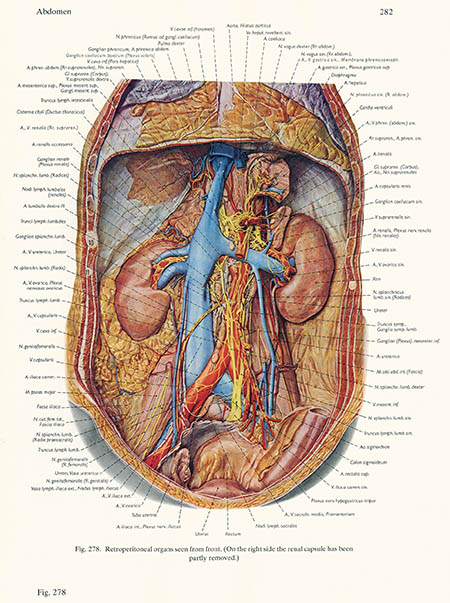

Retropertioneal organs seen from front

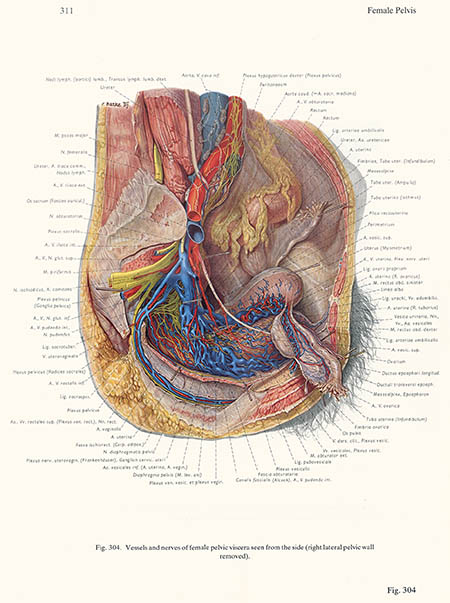

Vessels and nerves of the female pelvis viscera seen from the side

The Nazi origins of the text were always apparent. In early editions the artists even incorporated swastikas and SS symbols into their signatures. But this evidence was largely ignored by the medical community until Howard Israel and William Seidelman published a letter in JAMA calling into question the origin of Pernkopf’s plates, suggesting that “they may have been the victims of political terror.”5

Reluctantly, the University of Vienna agreed to investigate the matter and their senatorial review of “The Anatomical Sciences 1938–1945.” determined that “1377 bodies of executed persons, including eight of Jewish origin (although none from the Mauthausen camp complex) were transferred to the Vienna Department of Anatomy.” It is certain that at least some of these victims were used as preparations for Pernkopf’s work.

Hip joint with articular capsule, ligament and muscle origins

The University’s report raised a considerable debate in the medical ethics community. It’s easy to dismiss the brutal and fundamentally flawed Nazi science of Mengele or Fisher, but what do you do with exemplary science such as Pernkopf? There were letters and articles which argued both sides of the point.7 Citing the controversial nature of the work U&S withdrew publication of the atlas in the early 1990s but many of Pernkopf’s plates are still available in Clemente’s Anatomy.8

1. For more background on Pernkopf’s work see: Williams DJ. The history of Eduard Pernkopf’s Topographische Anatomie des Menschen. J Biocommun. 1988. Spring; 15(0):2–12. Which is online here.

2. The Topographische Anatomie des Menschen included Vol 1 (in two parts): Allgemeines, Brust und Brustgliedmasse (General Matters, Chest and Pectoral Limb), 1937. Vol 2 (in two parts): Bauch, Becken und Beckengliedmasse (Abdomen, Pelvis and Pelvic Limb), 1941. Vol 3: Der Hals (The Neck), 1952. Vol 4: Topographische und stratigraphische Anatomie des Kopfes (Topographical and Stratigraphical Anatomy of the Head), 1960

3. In all 153 of the 197 members of the faculty of medicine, including three Nobel laureates, were dismissed.

4. Ferner, Helmut (ed), Monsen, Harry (trans). Eduard Pernkopf. Altas of Topographical and Applied Human Anatomy, (2 vols). Baltimore: Urban & Schwarzenberg, 1980. All of the images here are scans from the second volume of the 1988 edition (which your narrator purchased at a thrift store) or from Clemente’s Anatomy.

5. Israel HA, Seidelman WE. Nazi origins of an anatomy text: the Pernkopf atlas. JAMA. 1996. Nov 27; 276:1633.

6. Senatsprojekt der Universität Wien. Untersuchen zur anatamischen wissenschaft in Wien 1938–1945. Vienna: Universität Wien, 1998. The report concluded that Pernkopf received at least 1,377 bodies, mostly political prisoners guillotined at the Vienna Landesgericht or shot by the Gestapo. The bodies were used for anatomical preparations, student dissections and for the Atlas.

7. For a review of the ethical controversy see: Hildebrandt S. How the Pernkopf Controversy Facilitated a Historical and Ethical Analysis of the Anatomical Sciences in Austria and Germany: A Recommendation for the Continued Use of the Pernkopf Atlas. Clinical Anatomy 2006. 19:91–100, which is online, or Atlas MC. Ethics and access to teaching materials in the medical library: the case of the Pernkopf atlas. Bull Med Libr Assoc 2001 Jan; 89(1): 51–58 (here).

8. Clemente, Carmine. Anatomy: A Regional Atlas of the Human Body. (3rd ed.), Philadelphia: Lea & Febiger, 1986. This edition included 89 of Pernkopf’s plates.

6 May 2011 ‧ Anatomicae

Next→