Detail, Isometrical Drawing of the Gettysburg Battle-Field, 1863. LOC

Gettysburg

John Bachelder

After Lee’s unlikely victory at Chancellorsville in May 1863 he led his Confederate Army of Northern Virginia through the Shenandoah Valley and across the Potomac River with the intention of bringing the war to the North.

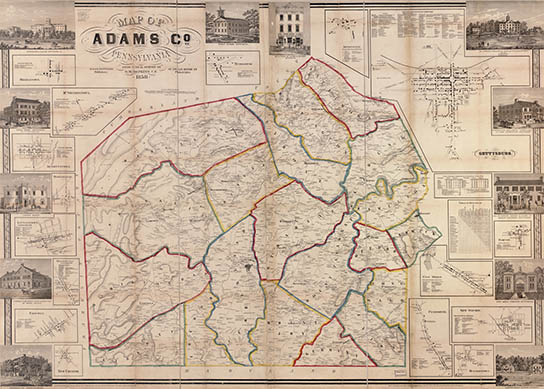

Lee didn’t have particularly accurate maps of enemy territory so his advance scouts, under the guise of map peddlers, went door-to-door confiscating every Pennsylvania county map they could find.1 This landowners map published by Griffin Hopkins in 1858 was the most detailed map of Adams county available at the time and would turn out the be especially useful to the Confederate command:

Map of Adams Co., Pennsylvania, 1858. LOC

Meade’s Union Army of the Potomac followed Lee into Pennsylvania and on the morning of Wednesday, 1 Jul 1863 elements of both armies converged on the town of Gettysburg. Although neither commander wanted an engagement here circumstances would dictate otherwise.

As the battle escalated both generals urgently concentrated their armies on the town – nearly 170,000 troops by Thursday afternoon. Over the three days between 1 Jul – 3 Jul fierce fighting would occur over an otherwise insignificant geography now etched into American history: Culp’s Hill, McPherson Ridge, Devil’s Den, Little Round Top, the Wheatfield, the Peach Orchard and Cemetery Ridge.

Despite heavy losses over the first two days Meade’s line had held. On Friday afternoon Lee tried one last desperate gambit, a massive cannonade and Napoleonic assault against the Union center – Pickett’s Charge. Although at one point the Rebels breached the Union line (“the high water-mark of the Confederacy”) the charge was driven back. Lee had been defeated and the next day he began the retreat back to Virginia.

It was the bloodiest battle in American history – more than 51,000 casualties including some 7000 killed. Lee had lost a third of his army and the Confederacy would never recover.

Timothy O’Sullivan, A Harvest of Death, ca.5 Jul 1863. LOC

John Badger Bachelder (29 Sep 1825 – 22 Dec 1894) was an artist, lithographer and amateur military historian in Boston. His interest in painting accurate renditions of battles led him, through family connections, to accompany the Army of the Potomac observing and sketching what he hoped would be “decisive battles.” Although he missed the battle, he arrived at Gettysburg within the week and spent nearly three months on the site researching every aspect the engagement, including surveying the battlefield, visiting field hospitals and interviewing both Confederate and Union officers and soldiers.

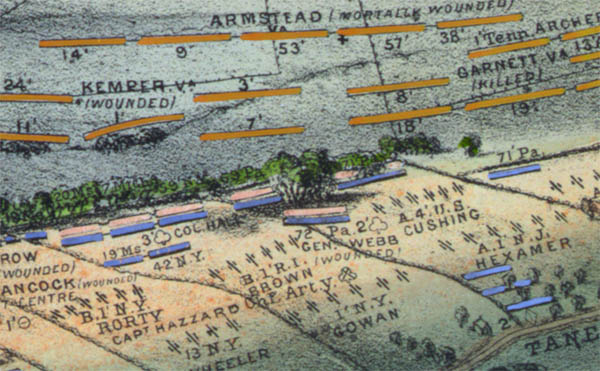

He compiled this research into a spectacular bird’s-eye map which showed the troop positions on all three days of the battle.2 Here is a detail from Pickett’s Charge centered around “The Angle:”

The map was endorsed by a number of Union commanders, including General Meade himself. Winfield Scott Hancock, who was seriously wounded during Pickett’s Charge, was so impressed that he sent Bachelder and his map to meet President Lincoln. Soon Bachelder was deluged with unsolicited first-hand accounts of the battle. He became, perhaps inadvertently, the first Gettysburg historian.

Meanwhile the War Department began its own mapping of the battlefield.

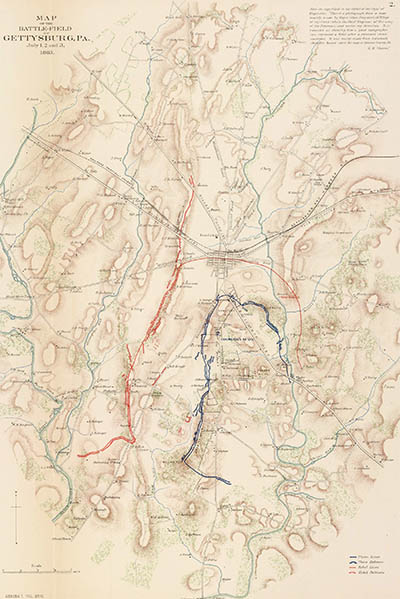

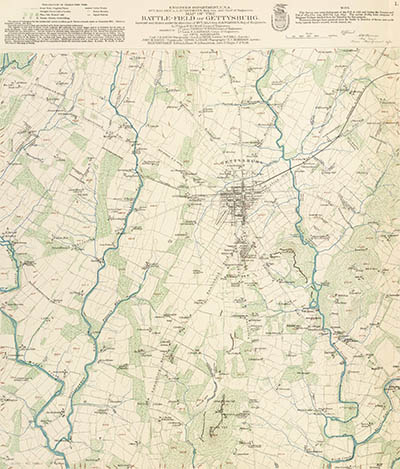

In Oct 1863 Emmor Cope, a sergeant with Brev. Maj. Gen. Gouverneur K. Warren’s Topographical Engineers made a “cursory reconnaissance sketch” of the battlefield on horseback and prepared this map which was reprinted in the Atlas to Accompany the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies: 3

Map of the Battle-field of Gettysburg, Pa. Rumsey Collection

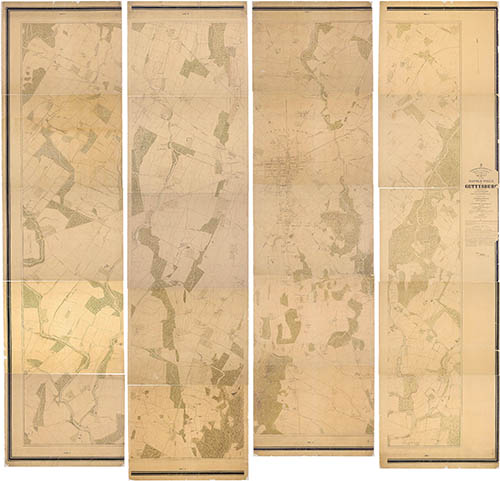

After the war Gen. Warren returned to Gettysburg with more time and resources. Between Oct 1868 – Oct 1869 his battalion, under 1st Lt. William Chase, performed the first proper survey of the battlefield. The resulting ink on linen map, at a scale of 1:2400, was large enough to include 4 foot contours and even what types of buildings and trees were present. Although historians consider it to be a better map of 1868 Gettysburg than of 1863 Gettysburg, it was still the most important historical survey done and is still the primary source for topographical research of the battlefield.

Map of the Battle-field of Gettysburg, 1868–06/1873. National Archives 305571

A field checked, 1:12,000 scale version of the Warren survey was published in the OR Atlas:

Map of the Battle-field of Gettysburg. Rumsey Collection

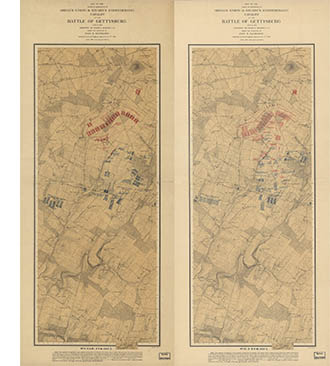

Bachelder spent the rest of his life researching the battle. He hosted veteran reunions, gathered correspondance from all ranks of both armies, commissioned a massive painting of Pickett’s Charge, wrote an “official” eight-volume history (which was never published) and eventually became responsable for overseeing the placement of markers and memorials on the battlefield.

In 1873 he created a new series of maps. Using Warren’s 1:12,000 scale survey as a base map, Bachelder overlaid troop positions based on information “…from the official reports, consultations on the field, private letters and oral explanations of the officers of both armies.” Eventually the series, which was updated several times, included 28 maps of not only the daily troop positions but in some cases hourly positions as well. Here are the daily maps:

Map of the Battle Field of Gettysburg. Big Map Blog

Here are a few of the hourly maps:

Gregg’s & Stuart’s Calvary at the Battle of Gettysburg. LOC

Some 140 years later Bachelder’s maps are still the most authoritative maps on the battle and are stiil yielding valuable insights. The geographer Anne Kelly Knowles asked the question “What could Lee actually see from his vantage point?” Using Bachelder’s map and modern GIS tools she and her team created a viewshed map and found that although Lee could see more of the battlefield than previously thought, he could see less of the Union position. She wrote: “Lee never had a clear view of enemy forces; the terrain itself hid portions of the Union Army throughout the battle. In addition, Lee did not grasp – or acknowledge – just how advantageous the Union’s position was.” This map shows Lee's view from the Lutheran Seminary cupola on the second day of the battle: 5

Viewshed map, second day. Courtesy Kelly Anne Knowles

There has been no other Civil War engagement – perhaps no other event in American history – that has been analyzed and written about as much as the Battle of Gettysburg, yet 150 years later there are still as many questions as there are answers. Batchelder’s maps undoubtedly have more answers awaiting for the clever historian to unlock.

1. For a general overview of Civil War mapping see: Stephenson, Richard, Civil War Maps: An Annotated List of Maps and Atlases in the Library of Congress, 2nd ed. Washington: Library of Congress, 1989 (online). For more about surveying the Gettysburg battlefield see: Musselman, Curt. “In the Footsteps of the Topographic Engineers at Gettysburg.” Professional Surveyor. 2011 Dec 31(12) (online).

2. See: Batchelder, John. Key to Bachelder’s Isometrical Drawing of the Gettysburg Battle-field, with a Brief Description of the Battle. Boston, 1864 (online).

3. The War of the Rebellion: a Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies (or just the OR) was published in 128 volumes between 1880-1894 (online). The 175-plate Atlas to Accompany the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies was published in 1895 (online).

4. If you were interested in the maps at the time Bachelder had a business proposition for you. This ad appeared in his popular guide Gettysburg: What to See, and How to See It (Boston, 1873):

5. The map is from “What Could Lee See at Gettysburg?” in Knowles, Anne Kelly (ed). Placing History: How Maps, Spatial Data, and GIS Are Changing Historical Scholarship. Redlands, CA: ESRI Press, 2008 (WorldCat).

A greatly expanded interactive map, covering the entire three days of the battle, was prepared by Knowles and her team for Smithsonian Magazine (online).

1 Jul 2012, updated 1 Jul 2013 ‧ Cartography