89

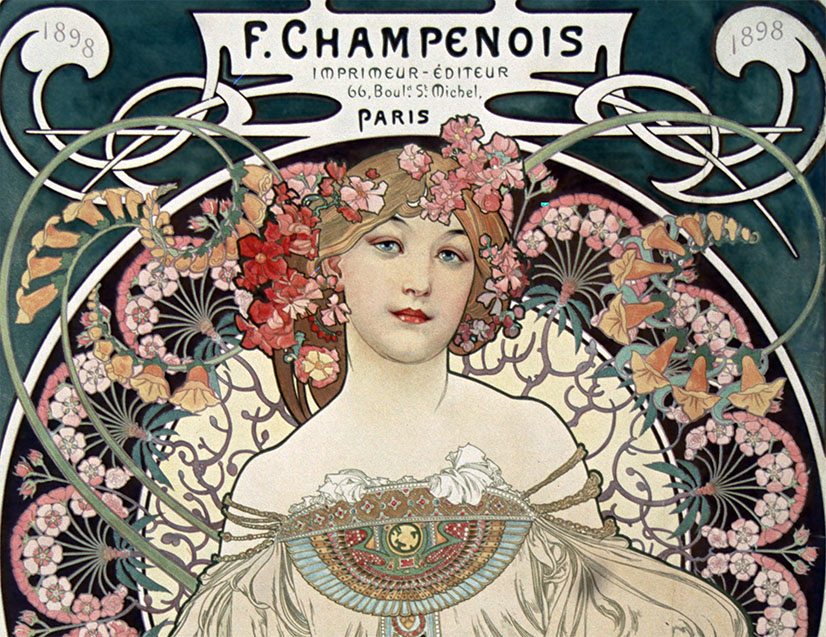

F. Champenois

Alphonse Mucha, part II

Here is a detail from a photo of an 1898 poster advertising Mucha’s primary printer and lithographer Ferdinand Champenois, of 66 Boulvd. St. Michel, Paris. The beautiful peasant woman in a neoclassical gown, the floral motif (especially in the hair) and the classical design of the gown (in this case Egyptian) are typical Mucha design elements. It may very well the most beautiful ad for a lithographer ever. Here is another version:

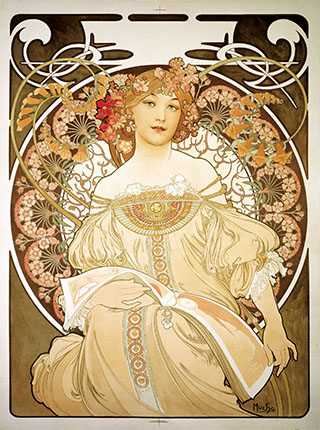

Poster. Reverie, 1898.

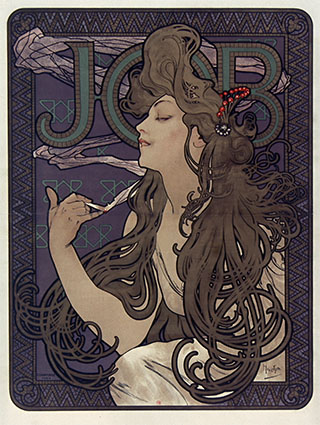

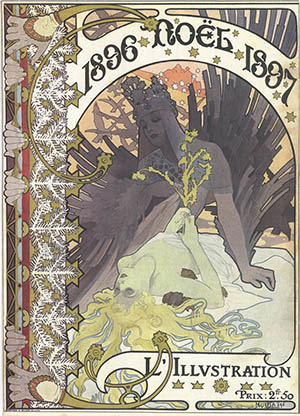

After Mucha was “discovered” by Sarah Bernhardt (see pt. I) he became an overnight sensation and soon was one of the most demanded commercial artists in Paris.1 He began to produce a steady stream of work including these early classics:

Poster. Job, 1896. BNF Gallica

Panel. Les Saisons, 1896.2 BNF Gallica

Cover, L’Illustration, Dec 1896

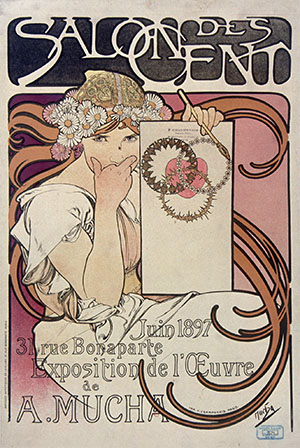

Over the next decade Mucha illustrated posters and decorative panels, book and magazine covers, advertisements, theater programs, menu cards, calendars and postcards. He even designed jewelry, theater sets and store interiors. At the height of his fame he was receiving as much as 2500 fr. for a commission and Champenois was selling his large works for as much as 25 fr. To get an idea of his prolific output his May 1897 solo exhibition at Leon Deshairs’ Salon des Cent included 448 works:

Poster. Salon des Cent, 1897. BNF Gallica

Posters. Têtes byzantines, 1897

Posters. Moët & Chandon, 1899. BNF Gallica

Panel (at least 3/4ths of it). La lune et les étoiles, 1900

Mucha was commissioned to decorate the Bosnia and Herzegovina Pavilion for the Exposition universelle internationale de 1900. The exposition, one of the first to feature the Art Nouveau aesthetic, made Mucha an international star. Soon his designs were being licensed throughout Europe and North America.

Panel, Bosnia and Herzegovina Pavilion, 1900

Madonna of the Lilies, 1905

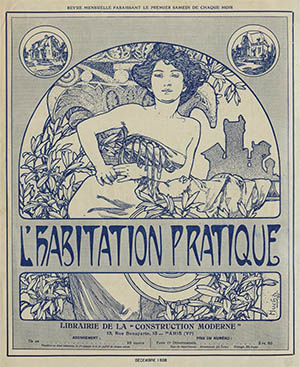

Cover. L’Habitation Pratique, 19083

Mucha never identified with the Art Nouveau movement, arguing that art was eternal and therefore could never be merely “nouveau.” As he stated in a 1904 letter to his fiancée Maruška: “You’ve no idea how often I am crushed almost to blood by the cogwheels of this life, by this torrent which has got hold of me, robbing me of my time and forcing me to do things that are so alien to those I dream about.” What Mucha was dreaming about about was a cycle of paintings detailing the history of the Slavs.

Convinced he would find his fortunes elsewhere, he left for America in Feb 1904. Over the course of several trips to America he painted oil portraits of the wealthy, produced commercial designs, taught art classes and finally, in 1909, found a new patron - Charles R. Crane, heir to the Crane Brass and Bell Foundry fortune.

With Crane’s patronage Mucha returned to his altier at the castle Zbiroh and began work on the Slovanská epopej (the Slav Epic). The twenty mammouth tempera canvases detailing the history of the Czechs and Slavs took him 18 years to complete.

Po bitvě u Grunwaldu, 1924. Bezgest.cz

Mont Athos (Svatá Hora), 1926. Bezgest.cz

Apotheosa z dějin Slovanstva, 1926. Bezgest.cz

Poster. Slovanská Epopej, 1930.

Mucha considered the Slav Epic to be the defining work of his career but the critical reception was unfavorable. They considered the work too academic, too spiritual, too nationalistic and argued that the work was hopelessly behind the times and “antimodern.”

Mucha died in Prague of pneumonia on 14 Jul 1939 shortly after being questioned by the Gestapo and his work faded into obscurity. It was only through the biographical efforts of his son Jiří and a renewed interest in Art Nouveau in the late 1960s that his achievements were properly recognized.

1. For a biography see: Mucha, Jiří, Geraldine Thompson, trans. The Master of Art Nouveau: Alphonse Mucha. Prague: Knihtsk, 1966. For a catalog of his vast oeuvre you’ll need more than one reference, here are a few: Rennert, Jack; Weill, Alain. Alphonse Mucha: The Complete Posters and Panels. Boston: G. K. Hall, 1984, or Bowers, David; Marin, Mary. The Postcards of Alphonse Mucha. Vestal, NY: Vestal Press, 1980, or Christian Richet’s Alphonse Maria Mucha: Catalogue des Livres.

2. Mucha’s panneaux décoratifs proved so popular that Champenois commissioned new versions in 1897 and 1900.

3. For a complete review of Mucha’s American trips see: Daley, Anna. “Alphonse Mucha in Gilded Age America, 1904-1921.” Diss. New School for Design, 2007, which is available online.

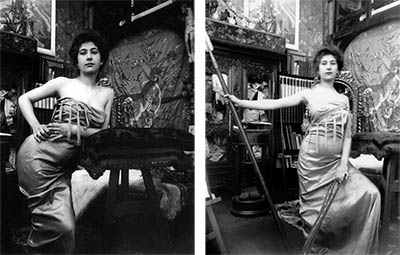

4. Mucha had long been a photographer and to save time and money he typically photographed his models. Here are some examples from the L’Habitation Pratique photo sessions:

5. For more information on the Slav Epic, including a description of each of the canvases, see John Price’s appropriately named The Slav Epic.

17 Mar 2011 ‧ Design