90

The Rhinoceros

When the spice ship Nossa Senhora da Ajuda set sail from India for Lisbon in Jan 1515, it included a unusual gift from Sultan Muzafar II to King Manuel I of Portugal – an Indian rhinoceros.1

The rhinoceros, the first seen in Europe since the ancient Roman menageries, arrived in Lisbon on 20 May and created great scientific and public interest. King Manuel eventually decided to give the rhinoceros to Pope Leo X and it set sail for Rome in Dec 1515. The ship, however, capsized in a storm and the rhino, chained to the deck, drowned. The carcass was recovered, stuffed, and exhibited impagliato at the Vatican in 1516.2

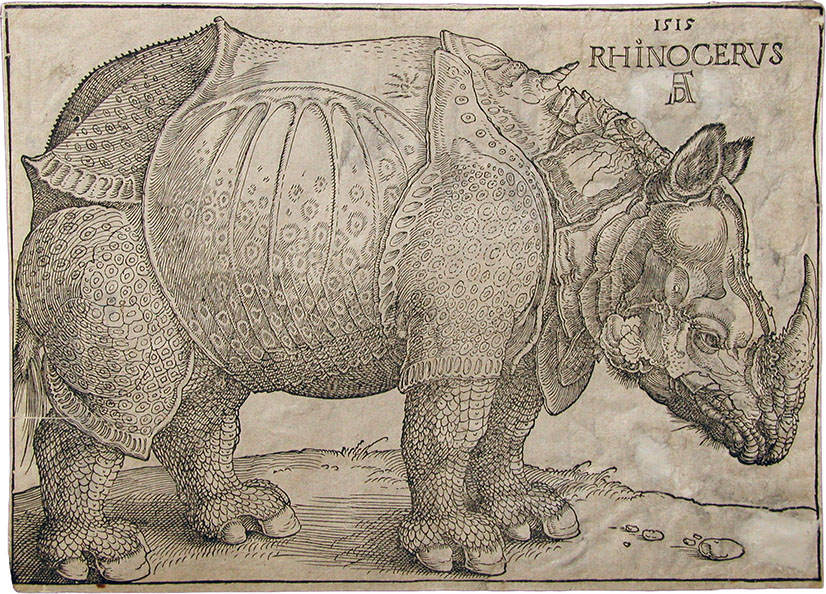

Although few saw the animal in person the news spread across Europe. Albrecht Dürer, in Nuremburg, received a sketch and a description from Valentin Ferdinand and from this he created several ink sketches and his famous woodcut (above).

Dürer, Rhinoceron, 1515

Dürer’s image was, to be kind, rather inaccurate. He interpreted the rhino’s plicae as scaly armored plates and he added several gratuitous additions such as a gorget and an augur-shaped second horn. Nevertheless, it was widely copied in Renaissance handbooks and encyclopedias and would serve as the prevailing European version of the rhinoceros for the next 250 years.

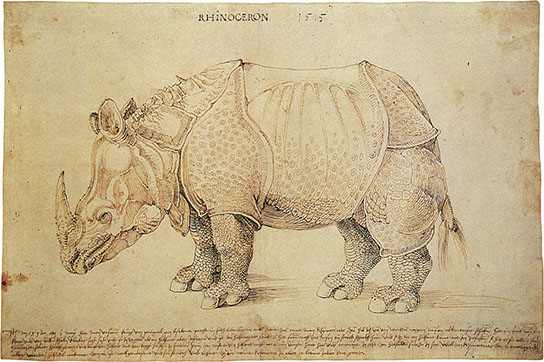

Here, e.g., is David Kandel’s copy after Dürer that appeared in Münster’s widely influential Cosmographia:

Kandel, in Cosmographia, 1598. Wikipedia

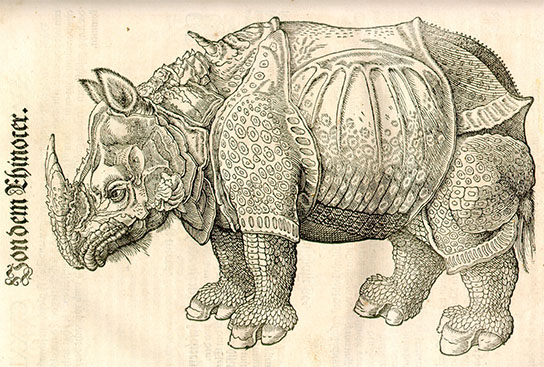

And here is a copy after Kandel after Dürer which appeared in Gesner’s Thierbuch (Historiae animalium):

Anonymous, in Thierbuch, 1565. Poemas del río Wang

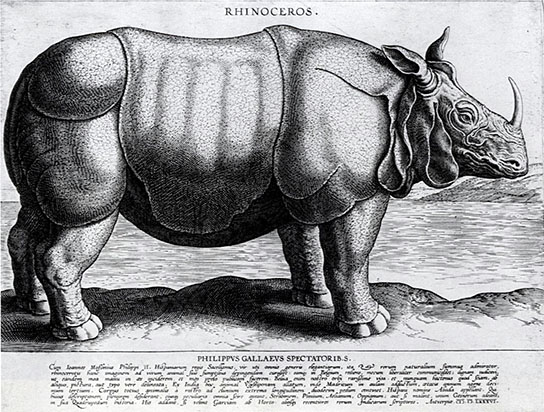

The second rhinoceros in Europe came to Lisbon in 1579 as a gift to King Phillip II, ruler of Spain and Portugal. Although it achieved only local fame, Phillippe Galle produced this engraving in Antwerp in 1586:

Galle, Rhinoceros, 1586. Fulltable

The next rhino appeared in London in 1684. In his diary John Evelyn described it as a “set of most dreadful teeth” and skin “loose like so much Coach leather...loricated like Armour...and of a mouse grey colour.” Unfortunately there is no known drawing.

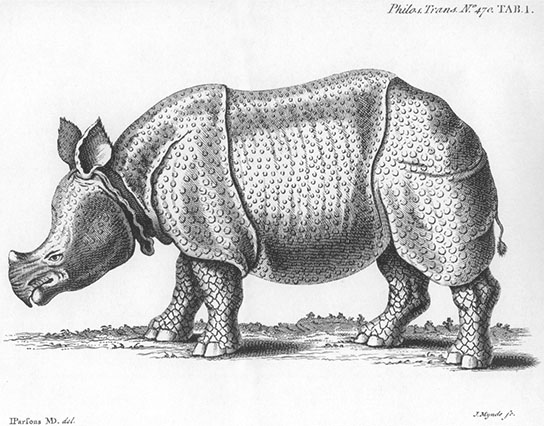

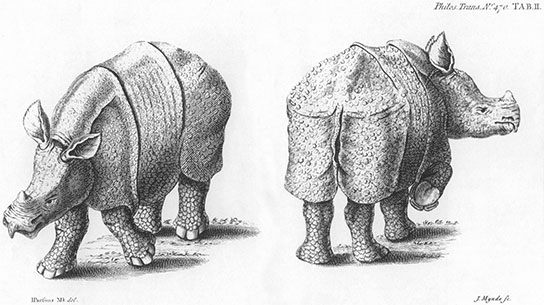

The fourth rhino in Europe arrived in London from Bengal via the ship Lyel in Jun 1739. Observing this animal Dr. James Parsons provided the first scientific description of the rhinoceros in 1743. His letter to the president of the Royal Society included three plates:3

Parsons, plate I, 1743. From ref. 3

Parsons, plate II, 1743. From ref 3

Although the plates were more accurate than earlier examples, Parsons still took Dürer-like liberties, such as the scales on the legs. A true representaion of the rhinoceros would take one more European specimen – but it would be the most famous rhino of all.

Clara, a 2-yo domesticated female rhinoceros was sold (or maybe gifted) by Jan Albert Sichterman, director of the VOC,4 to captain Douwe Mout van der Meer. The good captain transported Clara on his ship the Knappenhof from Assam to Rotterdam, where it arrived on 22 Jul 1741. After a brief rest in Leyden, the captain’s home, he intended to display Clara throughout Europe.

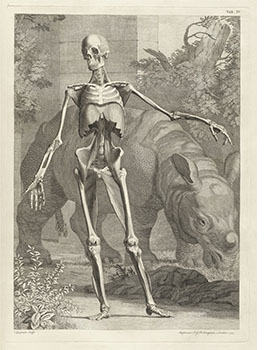

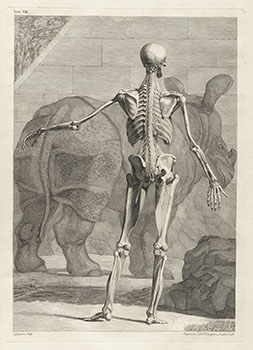

In a wonderful historical happenstance, at that very same place and time, Bernhard Siegfried Albinus was working on his seminal anatomy text Tabulae sceleti et musculorum corporis humani. His artist, Jan Wandelaar, decided to spruce up the background of the plates and in two of them decided to include images of the local attraction, the then 3-yo Clara:

Wandelaar, plates IV and VIII, 1749. NLM

The copperplate engravings were the first images of Clara, but more importantly, were a watershed in anatomical illustration and the first true and accurate depiction of a rhinoceros.

Van der Meer turned out to be a brilliant impessario. Using a specially built cart pulled by eight horses, he toured Clara throughout Europe and she was a sensation. Rhinomania soon swept through Europe. She was received by royalty and fed beer by commoners.5 Poems and songs were written about her. She was sketched, engraved and painted and her likeness appeared on everything from porcelain to snuff boxes to mantle clocks. French women ever wore their hair à la rhinocéros.

Souvenir engraving, 1747. Rijksmuseum

Jean-Baptiste Oudry, Clara the rhinoceros in Paris, 1749. Wikipedia

Pietro Longhi, Exhibition of a rhinoceros at Venice, 1751. Wikipedia

Van der Meer toured Clara for 17 years and became rich “beyond the dreams of avarice.” She died 14 Apr 1758 at the Horse and Groom in London.

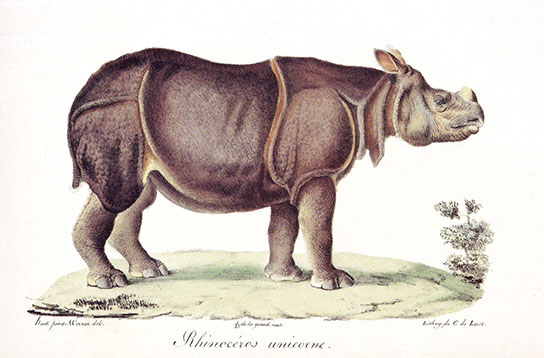

After Clara there really wasn’t any excuse to get your rhinoceros anatomy wrong. Here, as an example, is Étienne Geoffroy Saint-Hilaire’s engraving in Cuvier’s Histoire Naturelle de Mammiferes:

Saint-Hilaire. Rhinoceros unicorne, 1819

1. The Indian rhinoceros (Rhinoceros unicornis) is one of five surviving species in the family Rhinocerotidae of the order Perissodactyla. All rhino species are under pressure from a destruction of their habitat as well as poaching, mostly for their keratin horns which are used in Yemen as جنبية (jambīya or curved dagger) handles and in China as an aphrodisiac. CITES lists the Indian rhinoceros as ‘endangered.’

To get an idea of the value of a rhino to poachers, the smaller (and supposedly more ‘concentrated’) horns of Indian rhinos are, according to CITES, currently worth USD 59,000/kg.

2. For more information about the image of the rhinoceros in Renaissance Europe see: Clarke, T. H. “The Iconography of the Rhinoceros from Dürer to Stubbs. Pt I: Dürers Ganda.” The Connoisseur. Sep 1973. pp 2–13, and Clarke., T.H. “The Iconography of the Rhinoceros. Pt II - the Leyden Rhinoceros.” The Connoisseur, Feb 1974 pp. 113–122. Both of these are available online at the comprehensive, reference-level Rhino Resource Center.

3. Parsons, J. “A Letter from Dr. Parsons to Martin Folkes, Esq; President of the Royal Society, Containing the Natural History of the Rhinoceros.” Philosophical Transactions. 1743: (42), 523–541. The images are via the Jstor copy.

4. The VOC = the Vereenigde Oostindische Compagnie, or the Dutch East India Company.

5. Among other facts, The London Evening Post of 26 Jun 1755 described Clara’s diet thusly: “This Beast consumes daily 80lb of Hay and 30lb of Bread, besides a good Quantity of Wine and spirituous Liquors.” She also reportedly had an unnatural fondness for oranges, beer and having tobacco smoke blown up her nose.

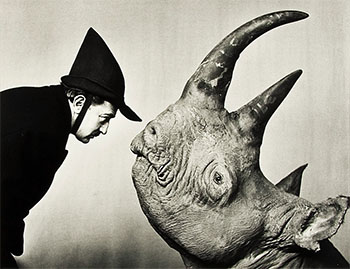

Phillippe Halsman. Dali and Rhinoceros, 1956

24 Mar 2011 ‧ Illustration