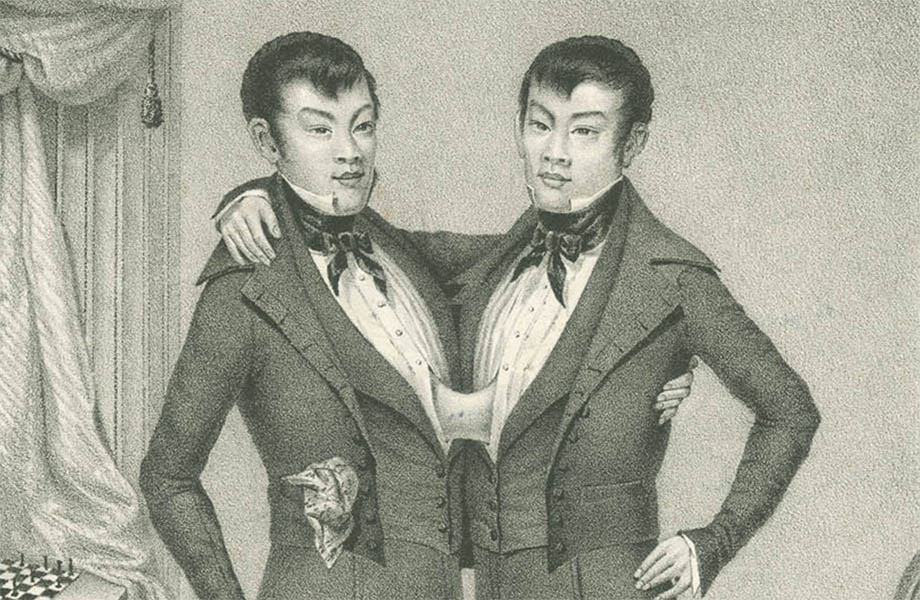

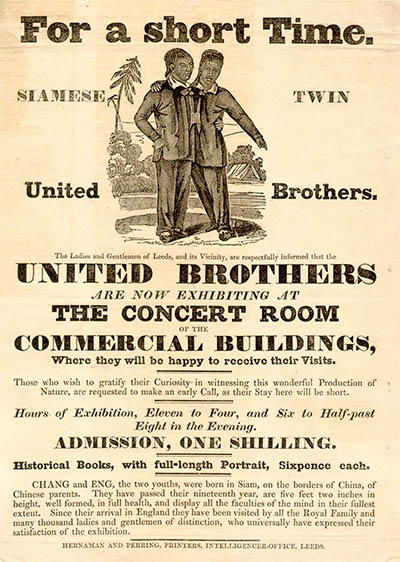

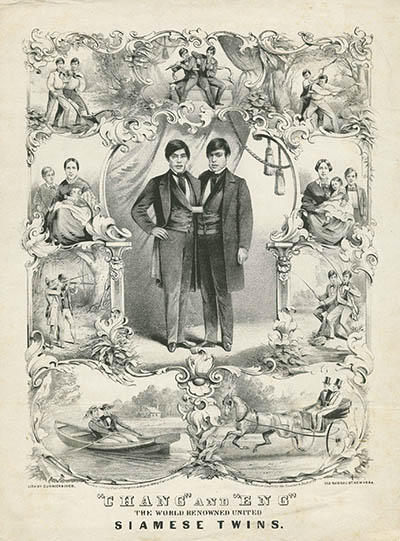

Eng–Chang, lithograph, P.A. Mesier & Co., 1839. UNC 1

Chang and Eng

Nineteenth-Century Broadsides and Engravings

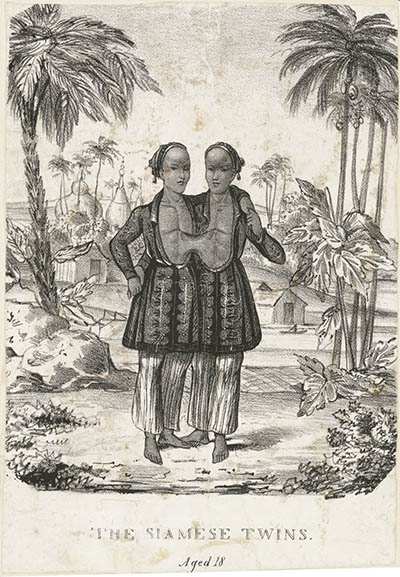

Chang and Eng were born 11 May 1811 on a houseboat on the Mekong River in Siam – the 5th and 6th of nine children of the Chinese fisherman Ti-eye and his Chinese/Malay wife, Nok. The twins, connected by a band of abdominal “cartilaginous substance” were considered an ominous sign and upon hearing the news of their birth Rama II, the King of Siam, condemned “the monsters” to death. Fortunately the King never carried through on his threat and the twins grew up living relatively ordinary lives, becoming known as simply the “Chinese Twins.” By the time they were teenagers they even found favor with the next king, Rama III, who showered them with gifts and sent them on diplomatic missions.

The British merchant Robert Hunter noticed the twins and convinced them their fortunes lay in the New World. After several years of negotiations Hunter and the American sea captain Robert Coffin took the twins, at age 18, to America. Upon their arrival in Boston the Daily National Intelligencer reported that “It was one of the greatest living curiosities that we ever saw...”

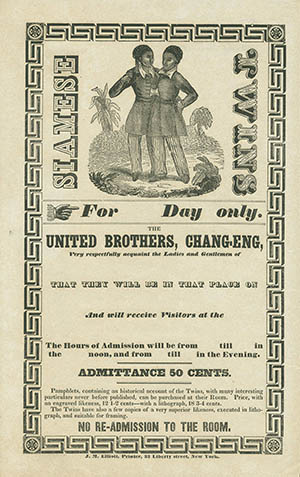

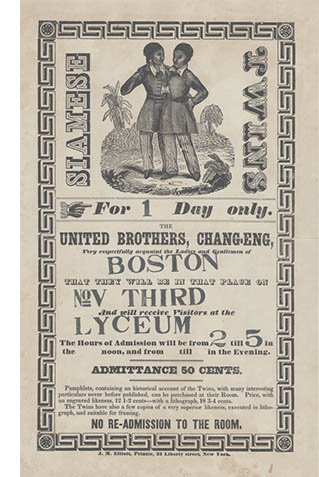

Coffin immediately began exhibiting the twins; first in the northeast, then a year in England and finally throughout the US and Canada.

To publicize their appearences Coffin had bills printed. The first broadside, left entirely to the local printer advertised the twins as “the Monster.” Horrified, Coffin quickly changed the billing to “The United Brothers.” These early American and British broadsides included a woodcut and various display faces and are typical not only of “freak show” advertising, but of Victorian advertising in general:

Right, UNC; left, North Carolina State Archives

Of course there were souvenirs available including a biographical pamphlet and this engraving, advertised as “a very superior likeness, executed in lithograph, and suitable for framing.”

By all accounts the twins’ schedule was gruelling and they became increasingly unhappy with Coffin, feeling that he was swindling them out of the receipts. In Jun 1832 – at age of 21 – they ended their relationship with Coffin and became, as they later wrote “their own men.” Over the next seven years they extensively toured on their own, including most of the Eastern United States as well as Cuba, France,3 Belgium and Holland. Of course, with these appearences came new pamphlets, books and lithographs (including the one above).

The twins became naturalized US citizens, adopting the last name Bunker and settled down in rural North Carolina. Comfortable, but unable to retire, they became gentleman farmers.

In a remarkable turn of events the the twins met the Wilksboro sisters Adelaide (Addy) and Sarah Ann (Sally) Yates. Against local opposition to the “unholy alliance” the twins married the sisters on 13 Apr 1843. Within a year both Addy and Sally had a child and eventually the twins would father no less than 21 children.

Of course, if two’s company and three’s a crowd than four is something else altogether. As their families grew the sisters started quarreling and eventually the twins set up seperate housholds. They would alternate between them – three days at a time – for the rest of their lives.

Gleason’s Pictorial Drawing Room Companion, 1853. Houghton Library

To provide for their growing families and multiple households the twins returned to touring and in 1860 they began a six-week engagement at P. T. Barnum’s American Museum. Barnum, perhaps more than any impresario of the day, understood advertising and he commissioned this lithograph illustrating their lives:

Chang and Eng, Currier & Ives, 1860

The War nearly wiped out the twins’ fortunes and accompanied by their daughters Katherine and Nannie, they left in 1868 for a European tour, including England, Scotland, Ireland, Germany and Russia. On the trip home Chang, who had become a heavy drinker, suffered a stroke leaving him partially paralyzed. The twins would never tour again. On the night of 17 Jan 1874 Chang suffered another – this time fatal – stroke. Eng immediately recognized his own fate and died three hours later of what was variously described as “shock” or “fright.” He was quite literally scared to death.

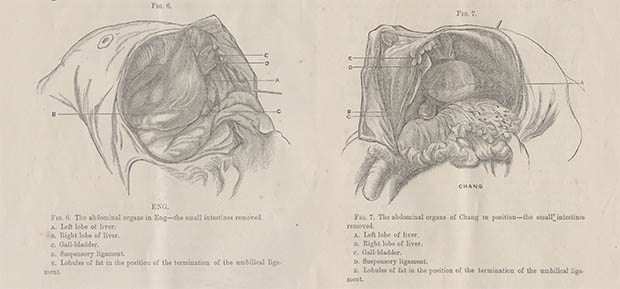

The widows allowed the College of Physicians of Philadelphia to perform an autopsy. They found that the band connecting the twins included a connected liver and detemined that they likely wouldn’t have survived separation as children, but would probably have survived surgery in the in 1870s.

Mosaic, 1874 autoposy report. North Carolina State Archives

Chang and Eng were the original Siamese twins, but they certainly weren’t the last. By the end of the 19th century, however, other famous cojoined twins, like Millie-Christine McCoy (the Two-Headed Nightingale) became part of the circus and the wood-type broadsides and lithographs became the glorious chromolithographic circus poster:

Millie Christine, the Two-Headed Lady, Strobridge Lithographic Co., 1882. From ref. 5

1. Unless otherwise noted the images here are from the University of North Carolina Wilson Library’s Eng & Chang Bunker: The Siamese Twins exhibit.

2. For more on the twins’ lives see: Daniels, Jonathan. “Never Alone at Last.” American Heritage. 1962 Aug 13(5) (online), or, Chickchester, Page. “Eng & Chang Bunker: A Hyphenated Life.” Blue Ridge Country. 1 Dec 1995. (online). The best biography is Wallace, Irving and Wallace, Amy. The Two. New York; Simon and Schuster, 1979. (WorldCat). The Wallace’s will forver have a special place in my heart for co-authoring one of my favorite books as a kid – The Book of Lists.

3. The first time the twins attempted to visit France in 1831 they were denied a visa because authorities thought that they “might deprave the minds of children” and “maternal impressions” would cause deformities in pregnant women. It was the noted naturalist Etienne Geoffroy Saint-Hilaire who finally convinced the authorities that the twins would not, in fact, cause any of these consequences. Ultimately the twins’ stay in Paris was less successful then they had hoped but, according to their letters, they quite enjoyed the city.

4. The twins formalin-preserved double liver is still on display at the Mütter Museum in Philadelphia.

5. Spangenberg, Kristin (ed). The Amazing American Circus Poster. Cincinnati: Cincinnati Art Museum, 2011 (WorldCat).

21 May 2013 ‧ Design