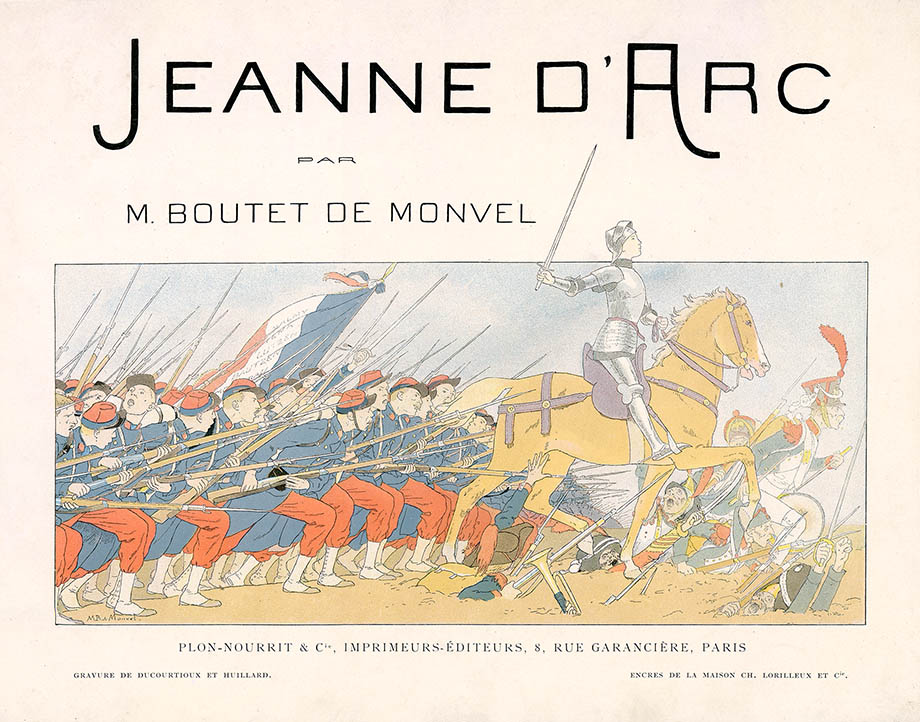

Joan of Arc leading the 19th century Armée de la Loire into battle against the Prussians

Jeanne d’Arc

Maurice Boutet de Monvel

Louis-Maurice Boutet de Monvel (18 Oct 1850 – 16 Mar 1913) was born in Orléans, France into a “family of gilt-edged artists.” In 1869 he enrolled in the De Rudder School and the following year in the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris, where he studied under Alexandre Cabanel. After serving in the Armée de la Loire during the Franco-Prussian War he enrolled at the Julian Academy under Jules Lefebvre and later studied watercolor with Carolus-Duran. His early paintings Le bon samaritain (The Good Samaritan) and La leçon avant le sabbat (The Lesson Before the Sabbath) even won awards at the Salon de Paris:

Le bon samaritain, 1878

La leçon avant le sabbat, 1880

Boutet married Jeanne Lebaigue in 1876 and they had a son in 1879. It soon became apparent that his academic oil paintings weren’t going to pay the family’s bills so he tried to find commercial work. “I went,” he said, “from publisher to publisher in search of orders for illustration – in vain.” He finally received a commission for the children’s books Les pourquoi de Mademoiselle Suzanne (Miss Suzanne’s Questions) 1 and La France en zigzag (Zig-zagging Across France).2 His work so impressed the publisher Charles Delagrave that Delagrave offered him the opportunity to contribute illustrations to his children’s periodical St. Nicolas.

His illustrations of nursery rhymes and children’s songs for St. Nicolas lead to the books Vieilles chansons et danses pour les petits enfants (Old Songs and Dances for Young Children) in 1883 and Chansons de France pour les petits Français (Songs of France for French Children) 3 in 1884.

BnF/Gallica

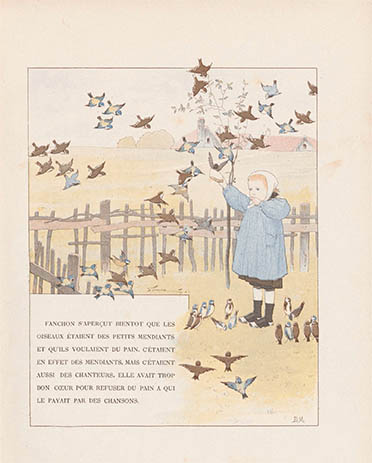

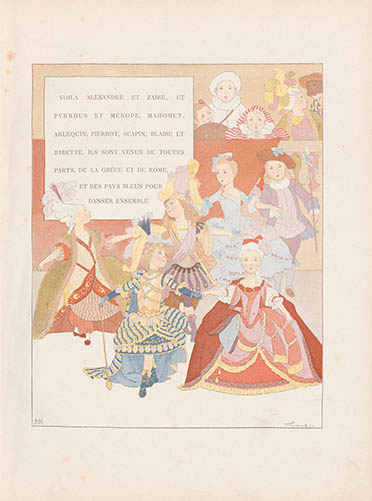

In 1887 he illustrated the future Nobel Laureate Anatole France’s Nos enfants (Our Children).4 It was this book that showed his genius for portraying the spirit of childhood and cemented his reputation as an illustrator:

Fanchon and the birds

The Costume Ball. BnF/Gallica

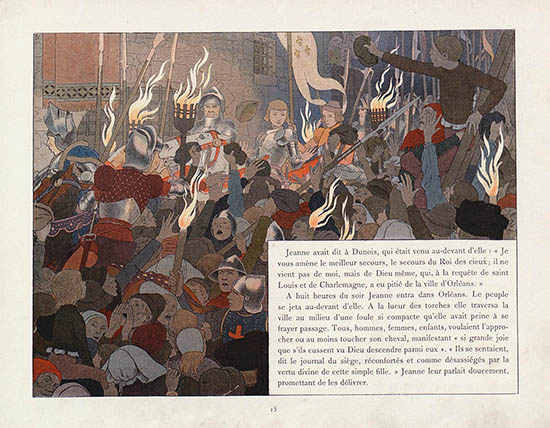

By this time Boutet had developed a spare illustration style that owed more to Japanese prints and the emerging Art Nouveau aesthetic than to his academic training. As he wrote:

“Of course, I found out directly that I could not put in the mass of little things which I had elaborated on my canvasses. Gradually, through a process of elimination and selection, I came to put in only what was necessary to give the character. I sought in every little figure, every group, the essence, and worked for that alone... This is the lesson taught me by the necessity of expressing much with the thin, encircling line of the pen.”

Discussing his muted watercolor palette he simply said: “[it’s] not color, really, it is the impression, the suggestion of color.”

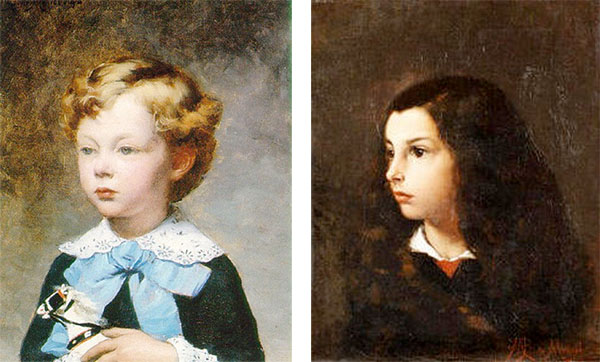

He tried to continue with his academic art, which he felt was his true calling, and after the success of Nos enfants was besieged by portrait work from wealthy Parisian families:

Nevertheless – aristocratic Third Republic parents aside – Boutet realized that his livelihood was now commercial illustration. Over the next ten years he did advertising posters, magazine articles and covers, opera and theater programs and, of course, more books.

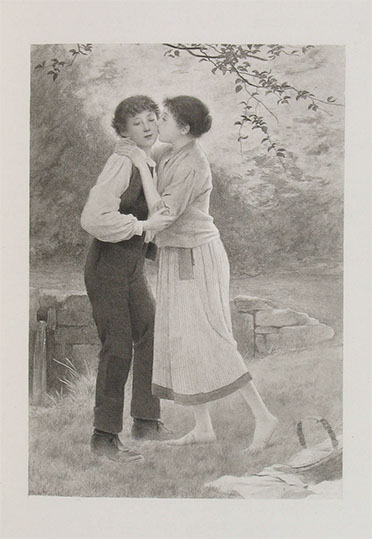

In 1890 the French art publisher Boussod, Valadon et Cie. commissioned Boutet to illustrate Ferdinand Fabre’s Xavière and printed his watercolors as photogravures:

Xavière et Landry, Iskandar Books

In the mid-1890s he began his next major book project. As he told Century magazine in 1899:

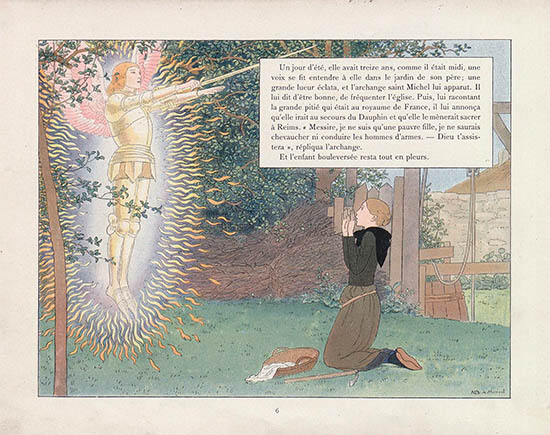

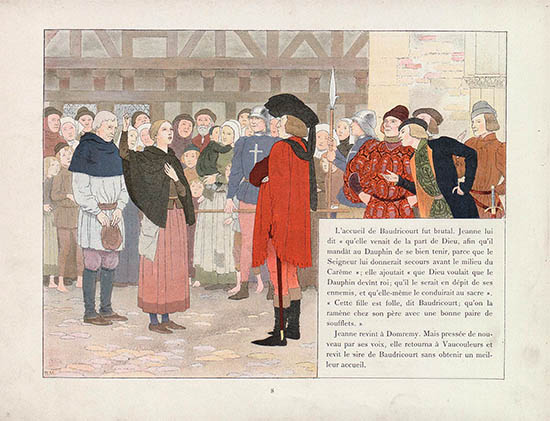

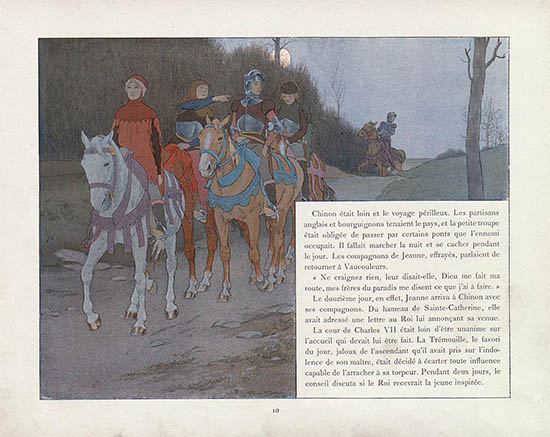

“The idea came to me like a flash, like an inspiration. My publishers asked me for another book for children; I had nothing in mind. One day as I was crossing the Tuileries I came suddenly upon the little statue by Frémiet, at the entrance of the Rue des Pyramides and when I looked up at Jeanne d’Arc I had my subject.6 Strange, isn’t it, that no one had ever thought of making a book of this kind before?”

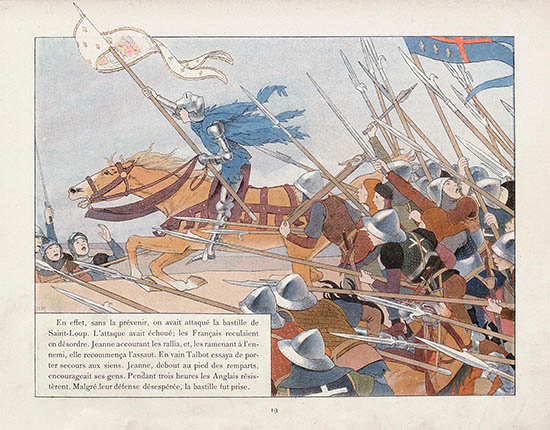

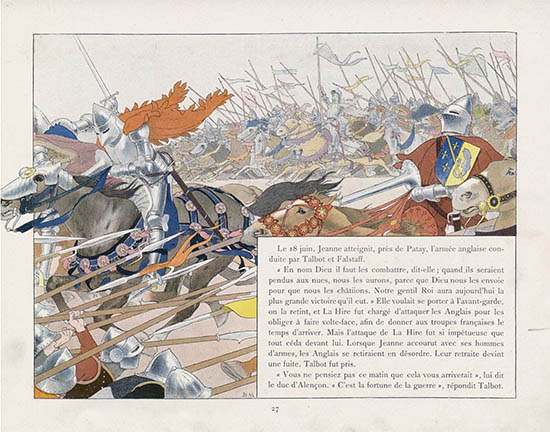

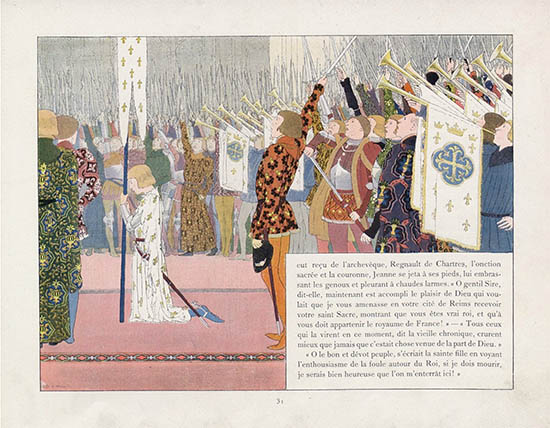

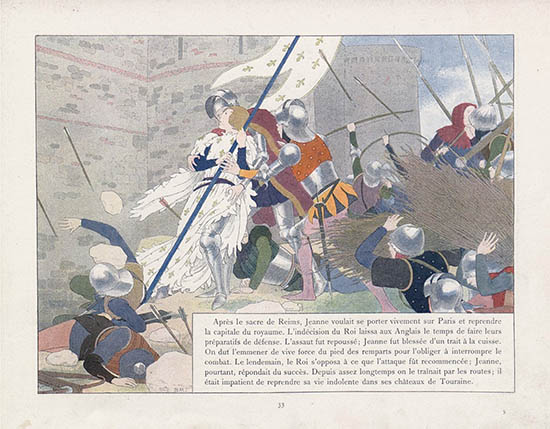

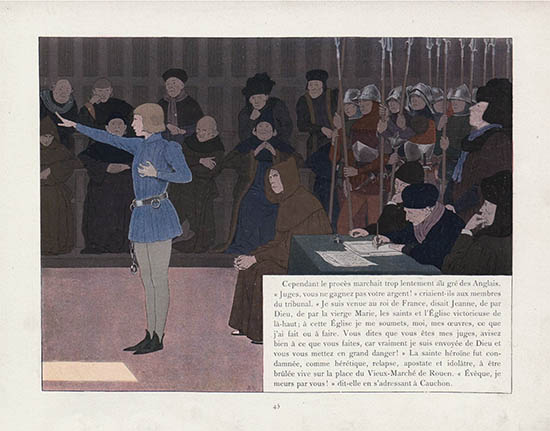

Boutet had spent his early years in Orléans, the childhood home of Joan of Arc and to him bringing the one true heroine of France to the page was an antidote to the national malaise following the disastrous Franco-Prussian War. The result – Jeanne d’Arc – was written, designed and illustrated by Boutet and published in 1896.7

For the book his watercolor paintings were engraved onto zinc plates (the zincotype or zincograph – a new process at the time) by the prolific Parisian firm of Ducourtioux and Huillard but the results ultimately disappointed Boutet, who felt that the softness of his original watercolors and “much of the finesse of the outline [was] lost.” Despite his objections, however, they remain the best lithographic reproductions in any of his books:

BnF/Gallica

Although his critics derided Boutet as “neither an historian or an author,” Jeanne d’Arc brought him international acclaim and is now widely seen as his magnum illustratus. It placed him among the premiere illustrators of children’s books – in the same category as Caldecott or Greenaway.

1. Desbeaux, Émile. Les pourquoi de Mademoiselle Suzanne. Paris: P. Ducrocq, 1881 (online).

2. Dupuis, Eudoxie. La France en zigzag: livre de lecture courante. Paris: Ch. Delagrave, 1882 (online).

3. Weckerlin, Jean-Baptiste. Chansons de France pour les petits Français. Paris: E. Plon, Nourrit et Cie, 1886 (online).

4. France, Anatole. Nos enfants: Scènes de la Ville et des Champs. Paris: Hatchette et Cie, 1887 (WorldCat, online). France was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1921 “in recognition of his brilliant literary achievements, characterized as they are by a nobility of style, a profound human sympathy, grace, and a true Gallic temperament.”

5. Fabre, Ferdinand. Xavière. Paris: Boussod, Valadon et Cie, 1890 (WorldCat).

6. Emmanuel Frémiet’s gilded bronze statue, Jeanne d’Arc, was commissioned by the French government in 1874 and 140 years later is still standing in the Place des Pyramides.

7. Boutet de Monvel, Louis-Maurice. Jeanne d’Arc. Paris: Plon-Nourrit et Cie, 1896 (WorldCat, online, online). The original French edition was published as a trade edition (above) and a deluxe portfolio of loose China-paper plates in an edition of 200. The first English translation was: Joan of Arc. Philadelphia: David McKay, 1918 (online). There have been dozens of other editions over the years and the bibliographic details are left an exercise to the reader.

22 Feb 2009, updated 17 Aug 2015 ‧ Illustration