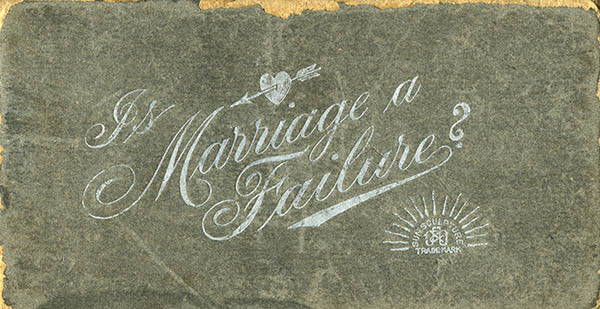

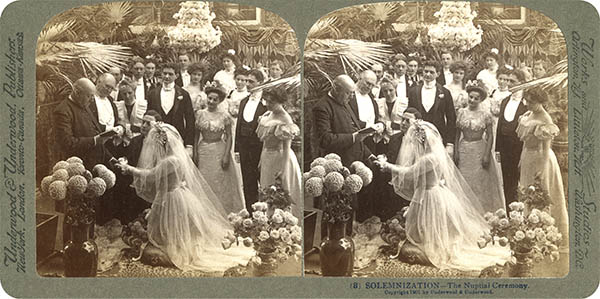

This stereo card, with the caption “Adoration – Alone at last” is no. 10 of 18 from the series Is Marriage a Failure? published by Underwood and Underwood in 1901. The stereographs consisted of two silver gelatin prints mounted, with a focal point 2.5" apart, on heavy, curved card stock designed to help with the 3D effect.1 Here is the box in all its edge-worn glory:

As previously discussed, Stereoscopic photographs (stereographs, stereo views or stereo cards), in the form of daguerrotypes, debuted at the 1851 Crystal Palace Exhibition in London. In America, Dr. Oliver Wendell Holmes, the famed physician and Fireside poet, designed a simple hand-held stereoscope in 1859 and became an early proponent of stereo photography:

“The stereograph, as we have called the double picture designed for the stereoscope, is to be the card of introduction to make all mankind acquaintances. The first effect of looking at a good photograph through the stereoscope is a surprise such as no painting ever produced. The mind feels its way into the very depths of the picture.” 2

Inspired by Holmes’ descriptions, Benjamin W. Kilburn, a photographer from Littleton, New Hampshire, began experimenting with stereo photography as early as 1865. Initially he photographed views of the nearby White Mountains, and later, scenic views throughout the US, Europe and Asia. The Kilburn Brothers and, later, B. W. Kilburn Co., were largely responsible for the popularization of the stereo view in 19th century America. Their inexpensive cards (and inexpensive Holmes viewers) allowed the growing middle and working classes to experience world travel.

In 1882, Elmer Underwood of Ottawa, Kansas, a subscription book salesman, and his brother Bert, a bookkeeper, decided to try selling Kilburn line of stereographs in the West. The venture was immediately successful, and soon the brothers added images from a number of photographers. Within a few years they established Underwood and Underwood Publishers and began to produce their own negatives. They moved the business to New York in 1891, and by the early 1900s were producing more than 25,000 cards per day.

At their height of popularity, between 1900―1920, it has been estimated that almost half the households in the US had a viewer and a collection of images.

Ultimately the stereograph became a victim of its own success. By the 1920s halftone stereo chromolithographs flooded the market, priced at less than a penny a piece. This, combined with the rising popularity of halftone-illustrated media (Time and Life magazines, e.g.), the emergence of the motion picture, and finally the Great Depression resulted in their decline. Eventually most of the publishers sold their negative libraries to Keystone, which continued to produced stereographs (mostly educational or technical views) until at least 1955.

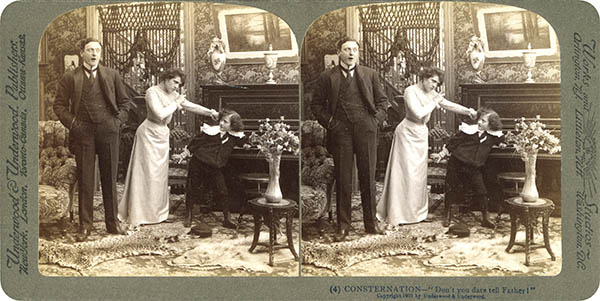

This card, missing from my set, was kindly supplied by Michael Deane of Gurnsey

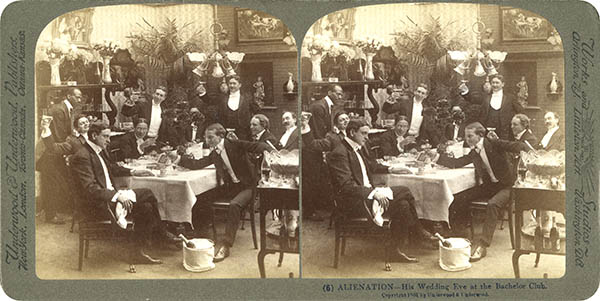

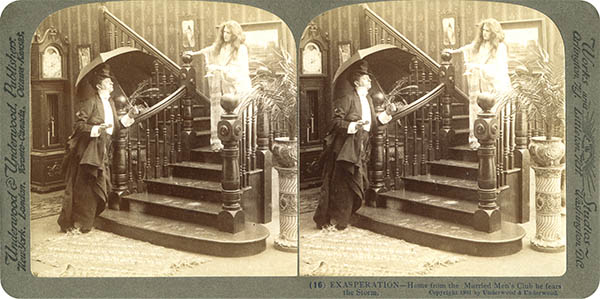

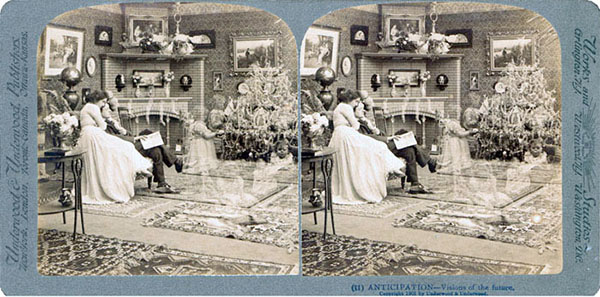

Between 1860 and 1930 the six major publishers – Underwood and Underwood, Keystone, B.W. Kilburn, H.C. White, Griffith and Griffith and Universal Photo Art – produced almost seven million different images and more than 300 million cards. Travel scenes were, by far, the most common, but other genres, including humorous or satirical courtship, marriage and children’s series were also popular. The Wedding set (usually 12 cards, but in our case 18), produced by all of the major publishers, included views of the courtship, the wedding march and ceremony, the wedding breakfast, and often a scene from the bridal suite, where the bride was dressed only in a petticoat. This last card, no doubt, was responsible for many a door-to-door sale.3

1. True Fact: Stereo views are largely wasted on your humble narrator. Any method for 3D images: including red-blue anaglyphs, polarized glasses, even a pair of Evans and Sutherland LCD shutter goggles I used at a pharmaceutical research lab in the late 1980s don’t work for me.

Later my all-time favorite GP (he smoked a pipe during office visits) told me that I simply don’t see in three dimensions. This explains why, if you throw something at me, I am very likely not to catch it.

2. Oliver Wendell Holmes. “The Stereoscope and The Stereograph” The Atlantic Monthly 3:20. June 1859. 738–48 (online). For more information about Holmes and the American stereograph see: Hamilton, George. Oliver Wendell Holmes―His pioneer Stereoscope and the later Industry. New York: The Newcomen Society, 1949 (online).

3. Although, honestly, the French were much better at this sort of thing.

15 Feb 2009, updated 14 Jan 2015 ‧ Photography