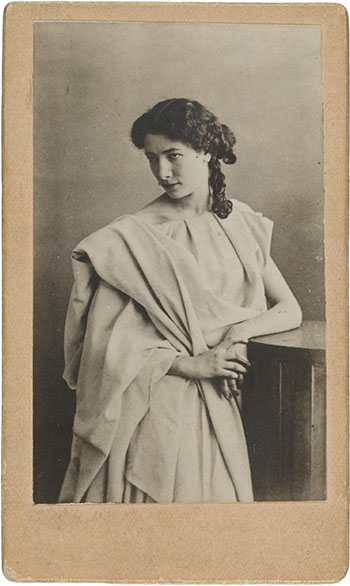

This photo of Sarah Bernhardt was taken by Nadar (Gaspard-Félix Tournachon) at his Boulevard des Capucines atelier in 1864. The sensual black drapery over her bare shoulder was – by design – rather suggestive. It also – again by design – conveniently concealed her illegitimate pregnancy. Even at the young age of 20 Bernhardt was already becoming the master génie de la réclame and was perfecting her greatest role – the role of Sarah Bernhardt.

Sarah Marie Henriette Rosine Bernhardt was born on 22 or 23 Oct 1844 to the Dutch Jewish courtesan Youle (Julie) Bernardt and an unknown father.1 Her mother had her raised by a series of nurses in Brittany then sent her off to the Augustine nuns at the Grandchamp school. In the ultimate act of rebellion she said she wanted to become a nun but the Duke of Morny, one of her mother's lovers, suggested acting and helped her gain admittance at age 16 to the Paris Conservatoire.

After two undistinguished years at the Conservatoire she began her career at the Comédie-Française. Her tenure there was brief – after only a few months she was summarily dismissed for slapping another actress across the face. She left Paris for Brussels and became a courtesan (just like mom taught her) and eventually became pregnant by her lover Henri, the Prince de Ligne. Maurice, her only child (whom she doted over for the rest of her life), was born on 22 Dec 1864.

In 1866 she returned to Paris and signed a contract with the Odéon Theatre. Her acting began to attract notice and after her command performance for Napoleon III as Zanetto in Coppée’s 1869 Le Passant she was on the verge of stardom.

Zanetto in Coppée’s Le Passant, 1869. BnF/Gallica

Her stardom, however, was put on hold by the Franco-Prussian War where she famously turned the Odéon into a military hospital. After the war she was welcomed back by the Comédie-Française and performed in plays by Hugo, Dumas fils, Voltaire and Racine.

Junie in Racine’s Britannicus, 1872. BnF/Gallica

Phèdre in Racine’s Phèdre, 1874. BnF/Gallica, Getty

Marguerite in Dumas fil’s La dame aux camélias, 1880. BnF/Gallica

Each of her dramatic roles increased her fame and by 1880 she was the most celebrated actress in Paris – she had become la devine Sarah.

Her stardom owed as much to her eccentric, flamboyant and scandalous personal life as it did to her acting. She had public affairs with playwrights, actors and artists.2 She travelled with a menagerie of exotic animals, including a boa and an aligator named Ali-Gaga.3 She dressed in Byzantine and Oriental gowns and perhaps most bizarrely, slept in a coffin and performed with a human skull. To her detractors she was completely unapologetic and said simply “Quand même” (So what). “My fame,” she wrote, “had become annoying for my enemies, and a little trying, I confess, for my friends.”

The bat hat, ca. 1882. Harvard

Her portrait was painted by the most celebrated artists in Paris, her advertising posters literally defined French Art Nouveau, but it was her photographs that turned her into an idol. She was the first to fully grasp the potential of the relatively new cabinet card and, unlike her contemporaries, had multiple images made of nearly every one of her roles. She didn’t just pose but performed for the camera. As Heather McPherson noted she used photography to “simulate and recreate the visual and emotional dynamics of her performance.” 4

Melandri, Nadar and Otto in Paris, Downey in London and Sarony in New York all photographed her and many others licensed these photographs. Of course these photos also served as the basis of lithographs, chromolithographs, photogravures or halftones. Sarah became perhaps the most photographed and illustrated person of the 19th century.

In 1880 Sarah formed her own company and left Paris to tour Europe and the US, performing Phèdre, Hernani, and Froufrou.5 Although she was ambivalent (to say the least) about America, the audience – most whom didn’t understand a word of French – loved her. This began a cycle of wildly successful world tours that provoked both jealously and anger followed by a triumphant return to the Paris stage. Her friend later commented that “You could never mention any place, however outlandish, to which she had not been.”

She returned from America in 1881 with enough money to buy the Théâtre de l’Ambigu and Victor Sardou began writing roles for her, including Fédora, Théodora and La Tosca.

Fedora in Sardou’s Fedora, 1882. BnF/Gallica

Empress Theodora in Sardou’s Theodora, 1884. BnF/Gallica

Cleopatra in Sardou’s Cléopâtre, 1890. BnF/Gallica

In 1891 she embarked on yet another world tour – two and a half years through Europe, North and South America and Australia. When she returned to Paris she bought the Théâtre de la Renaissance and as actor/director/producer performed in roles that many consider to be her most innovative.

Leah in Darmont’s Léah, Boston, 8 Jan 1892. BnF/Gallica

Gismonda in Sardou’s Gismonda, 1894. BnF/Gallica

Photine in Rostrand’s La samaritaine, 1897. BnF/Gallica

In 1905 Sarah left for her farewell tour of the Americas and while performing La Tosca in Rio de Janeiro she injured her knee. She continued to tour and perform but the knee never properly healed and she was in constant pain. At the age of 71, despite the objections of those around her, she had the leg amputated.6 Eight months later she was performing La dame aux camélias in a wheelchair. Her critics named her “Mère la chaise,” but she kept performing (because – Quand même). In 1916 she performed with the Théâtre aux Armées for the troops at the front and in 1918 began her third and last farewell tour of America.

Jeanne in Bernard’s Jeanne Doré, 1913. Her last new stage role. BnF/Gallica

Sarah died of kidney failure on 26 Mar 1923 and on Maundy Thursday tens of thousands of people lined the streets of Paris for her funeral cortège. The New York Times wrote in their obituary that “No temperament more histrionic than Mme Bernhardt’s has, perhaps, ever existed.” At her gravesite it was reported that a young actress, overcome with grief, yelled out “But immortals do not die!”

They say you die twice – once when you’re buried and again when your name is no longer mentioned. So that young actress turned out to be right – Sarah may very well be immortal. Her attention to her craft, her life lived without reservation or apology and her mastery of the media has been the template every celebrity has aspired to since, yet a century later there still has been no one who can equal her fame.

Dave Hughes, Père Lachaise, 7 Sep 2011

1. The best recent biography is: Gottlieb, Robert. The Life of Sarah Bernhardt. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2010 (WorldCat). Alternately, for her take-with-a-grain-of-salt autobiography see: Bernhardt, Sarah. My Double Life: The Memoirs of Sarah Bernhardt by Sarah Bernhardt. London: Heinemann, 1907 (French, English)

2. She reportedly had affairs with Napoleon III, Edward, Prince of Wales, Victor Hugo (who gave her a human skull after her 1877 performance in Hernani), Charles Haas, Jean Mounet-Sully, Gustave Dore, Jean Richepin and Louise Abbéma. She also had “lifelong habit of automatically sleeping with her leading men,” often in the dressing room after performances. She was even inexplicably, albeit briefly, married to Greek military officer/actor Aristides Damala (who died at age 34 from his morphine addiction).

Victor’s gift to Sarah. V&A

3. Her personal zoo, which she travelled with, included at various times Ali-Gaga, the alligator that died after too much milk and champagne, a boa constrictor that she shot herself after it swallowed a pillow, Cross-ci Cross-ça, the Chinese chameleon, a cheetah, a leopard, a pair of lion cubs, a lynx, Bizibouzou the monkey and Darwin the dog.

4. McPherson, Heather. “Sarah Bernhardt: Portrait of the Actress as Spectacle” in The Modern Portrait in 19th Century France. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2001 (WorldCat). For more about Sarah and the photograph see: Ockman, Carol and Silver, Kenneth, et. al. Sarah Bernhardt: The Art of High Drama. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2005 (WorldCat).

5. For more on Sarah’s 1880 tour see: Marks, Patricia. Sarah Bernhardt’s First American Theatrical Tour, 1880–1881. Jefferson, NC: McFarland, 2003 (WorldCat).

6. She wrote to one of her former lovers, the surgeon Samuel Pozzi, asking him to amputate her leg above the knee. If he did not help her, she threatened to shoot herself in the leg and then it would have to be cut off. “I want to live what life remains to me,” she wrote, “or die at once.” He had no choice, obviously, and authorized the surgeon Maurice Denucé to perform the operation.

30 Aug 2015 ‧ Photography