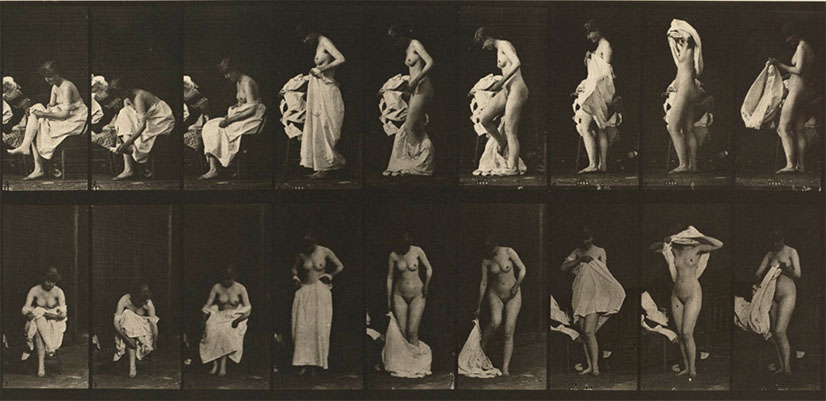

Detail, Animal Locomotion Vol 4, plate 498 – Miscellaneous phases of the toilet (model no. 7). From ref. 1

87

Animal Locomotion

Eadweard Muybridge

Eadweard James Muybridge (AKA Edward Muggeridge or Eduardo Santiago Muybridge, among others) was born in London on 9 Apr 1830. At 19 he emigrated to America and ended up as a bookseller in San Francisco. Around 22 Jul 1860 he was involved in stagecoach accident north of Fort Worth and suffered severe (and permanent) head injuries.2 He returned home to England to recuperate and, during what has been called his lost years, learned the art of wet-plate photography.

Muybridge resurfaced in San Francisco around July 1866 and soon made a name for himself (under the pseudonym Helios) as a landscape photographer:

Valley of the Yosemite. From Mosquito Camp, 1872. From the Corcoran Gallery

His work caught the attention of Leland Stanford, former governor of California, rail magnate and thoroughbred breeder. In 1872 Stanford commissioned Muybridge to scientifically settle a longstanding bet that all four hooves of a horse are off the ground at the same time – a concept known as “unsupported transit.” Although Muybridge was skeptical he began photographic experiments.

Muybridge’s work on the horse problem, however, was interrupted by a small domestic matter. In 1874 He murdered his wife’s lover, stood trial, and after being acquitted spent several years in Central America.3

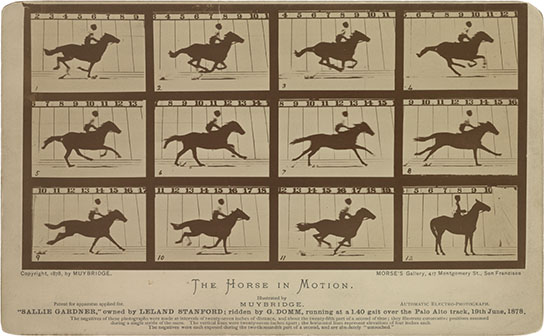

When Muybridge returned to California he again took up the horse problem and in 1877 he successfully captured Stanfords’s horse Occident mid-stride and settled the question of unsupported transit. With Stanford’s support he continued to work on the process of capturing motion and developed a system of electrical trip wires connected to shutter boxes and stereo cameras. When the trip wire was depressed it completed a circuit that activated the shutter and exposed the wet plates. He would eventually patent the system as the “Automatic Electro-Photograph.”4

On 19 Jun 1878 he tested this setup with Sallie Gardiner. The resulting 24 frames were a watershed in photography. Muybridge had managed to stop the arrow of time and forever changed the way we perceive the world.

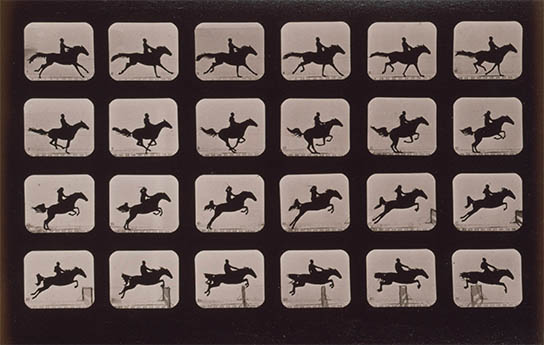

Muybridge continued to refine his technique and within a year or two was using a system with 24 wet-plate cameras. He published many of these studies in The Attitudes of Animals in Motion:5

Plate 45. Horses. Leaping a 3 ft. 6 hurdle. LOC LC-USZC4-13746

Plate 201. Skeleton of horse. Leaping. Leaving the ground. LOC LC-USZC4-13863

The photos had brought Muybridge fame and he turned his attention from stopping time to reassembling time. In 1882 he invented the zoopraxiscope (or phenakistiscope) - a glass disc with outlined images that when viewed through his machine would appear to move. It was for all practical purposes the first motion picture.6 He lectured and wrote extensively about the process and even set up a theater, the Zoopraxigraphical Hall, at the 1893 Chicago Columbian Exposition.

A Couple Waltzing. LOC LC-DIG-ppmsca-05949

After a falling out with Stanford in 1879 Muybridge spent several years travelling and lecturing before the University of Pennsylvania promised to underwrite a “scientific” study of animal and human motion. He began photography, with a 24–48 camera setup, in the spring of 1884 and over the next year and a half he took more than 100,000 4×5 dry plate negatives.

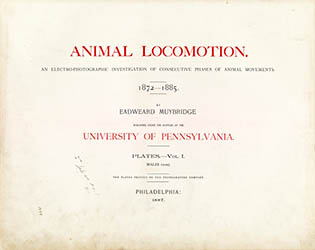

It would take Muybridge more than a year to select and prepare plates for publication. The result – the landmark and monumental Animal Locomotion included 11 volumes, 781 plates and 19,347 individual photographs. It included, according to the prospectus, “Men, Women and Children, Animals and Birds, all actively engaged in walking, galloping, flying, working, jumping, fighting, dancing, playing at base-ball, cricket and other athletic games, or other actions incidental to every-day life, which illustrate motion or the play of muscles.”7

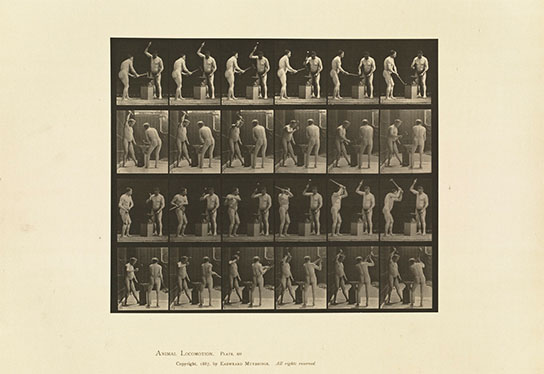

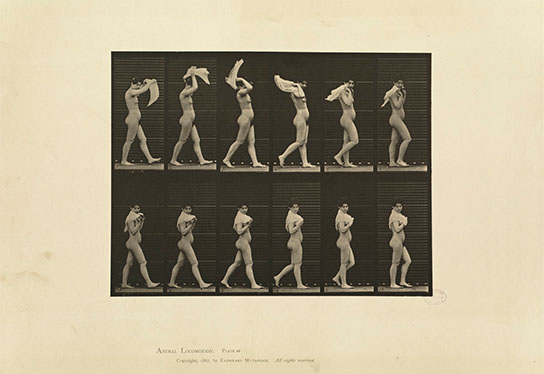

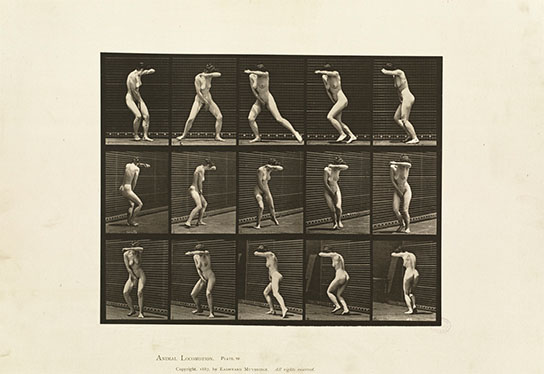

Muybridge photographed men engaged their typical activities: walking, running, performing athletics or at their occupations. Most of the models were students or faculty of the University, although there were a few surprises. Model no. 51 (described as a “well-known art instructor”) was Thomas Eakins and no. 95 (“an ex-athlete, aged about 60”) was Muybridge himself. He also recruited some of the models himself, such as nos. 44–45, the blacksmiths Redinger and Breen (and where he found blacksmiths willing to pose nude is another question altogether).

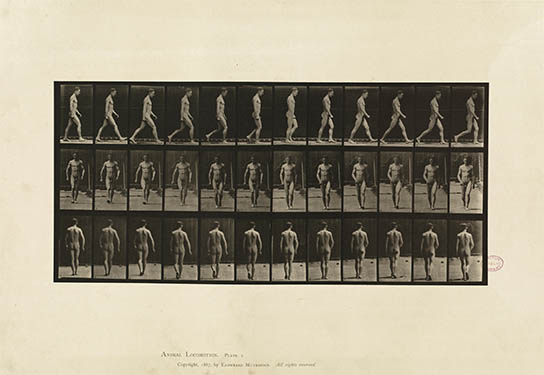

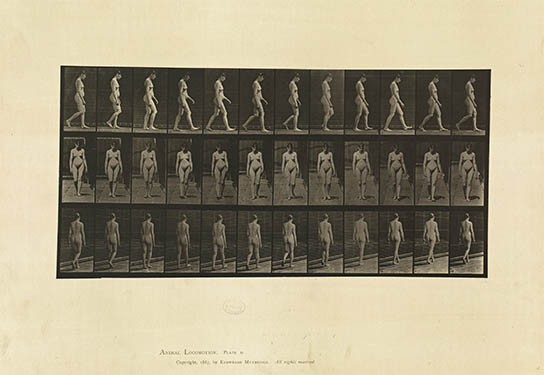

Plate 1 – Walking (model no. 36)

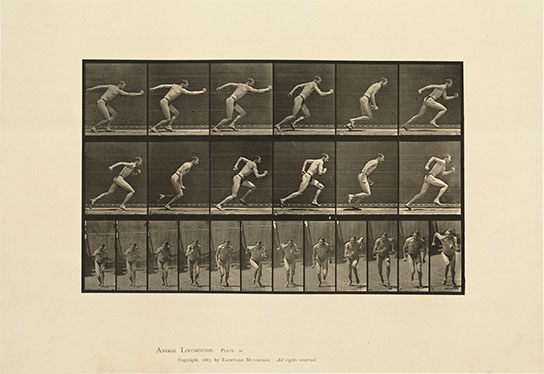

Plate 59 – Starting for a run (shoes) (no. 37)

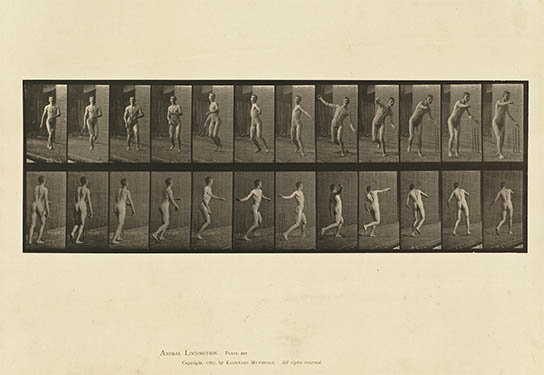

Plate 289 – Cricket; round arm bowling (no. 69)

Plate 377 – Blacksmiths, two models, hammering on anvil (nos. 44, 45)

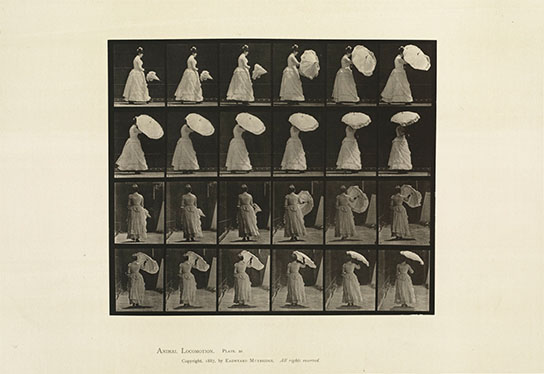

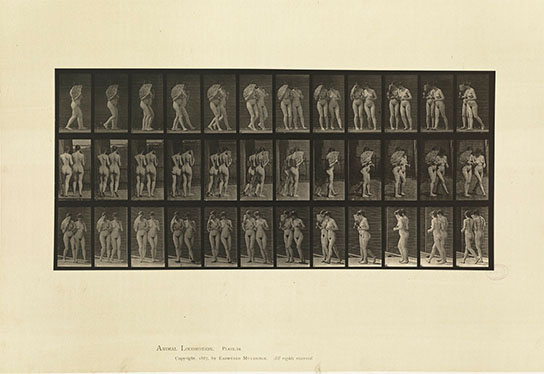

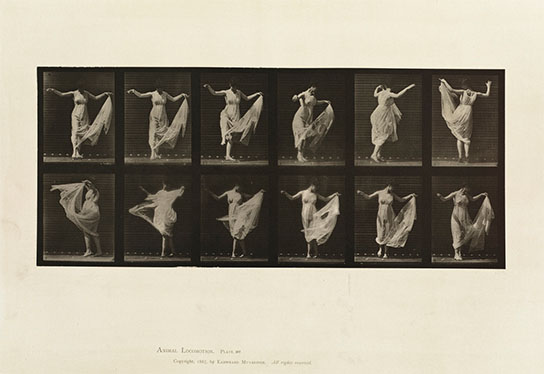

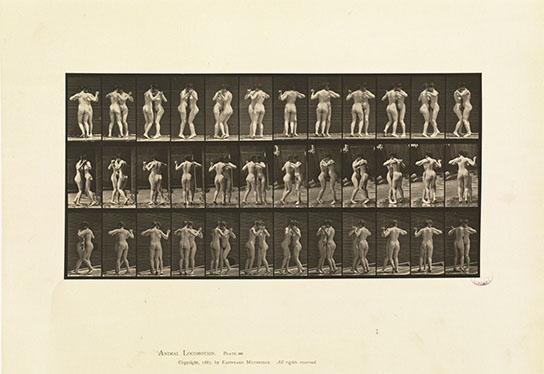

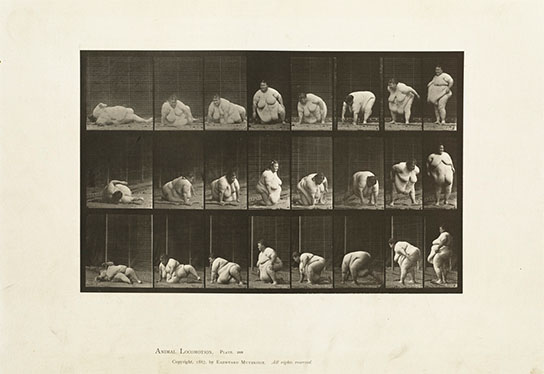

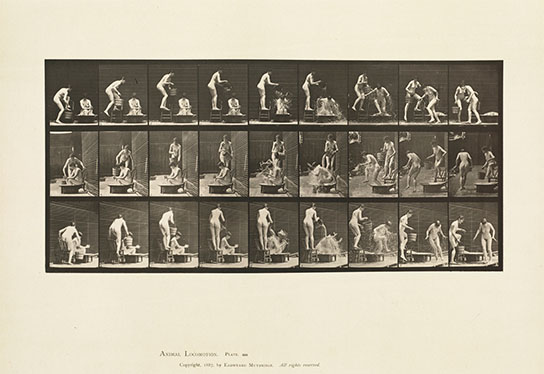

He photographed the women engaged in walking, dancing and a progression of increasingly contrived and bizarre movements and situations. Most of the women were artist’s models (i.e., prostitutes) supplied by Eakins.8 Muybridge’s favorites (or at least the most willing) were no. 1, Blanche Epler (“widow, aged 35, somewhat slender and above medium height”) and no. 8, Catherine Aimer (“single, between the ages of 17-24”). Also notable is Miss Cox, no. 20 (“unmarried and weighs three hundred and forty pounds”).

It’s difficult to know exactly what Muybridge was thinking (since he was an insane genius) but 120 years later many of these studies still look like Victorian porn under a thin guise of science.

Plate 13 – Walking (no. 1)

Plate 38 – Walking, opening parasol (no. 3)

Plate 40 – Walking, throwing handkerchief over shoulder (no. 13)

Plate 54 – Walking, two models (one flirting with a fan), arm in arm, turning around (nos. 1,8)

Plate 73 – Turning around in surprise and running away (no. 8)

Plate 187 – Dancing (fancy) (no. 12, Miss Larrigan)

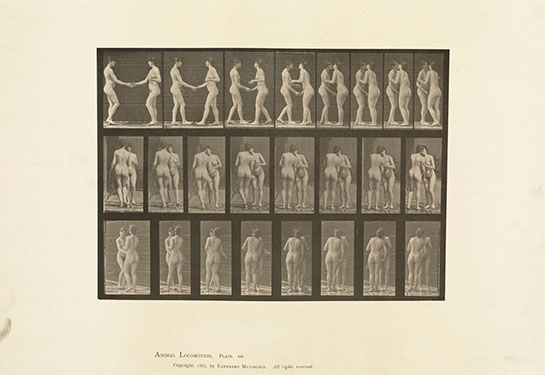

Plate 196 – Dancing, waltz, two models (nos. 1,8)

Plate 268 – Arising from the ground (no. 20)

Plate 408 – Two models, 1 pouring bucket of water over 8

Plate 444 – Two models shaking hands and kissing each other (nos. 1,8)

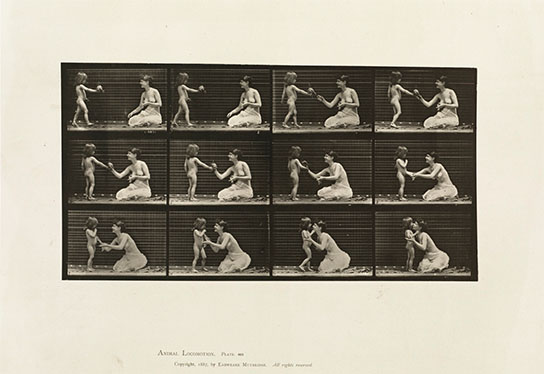

Plate 465 – Two models, child N70, bringing bouquet to 12

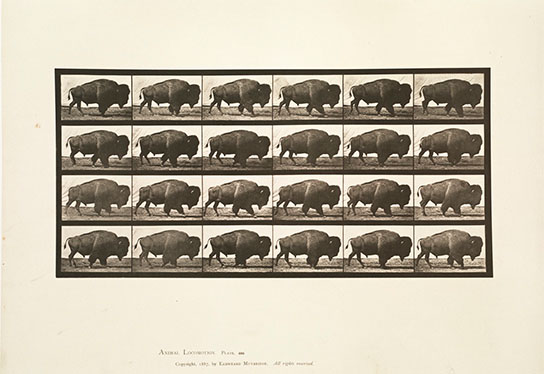

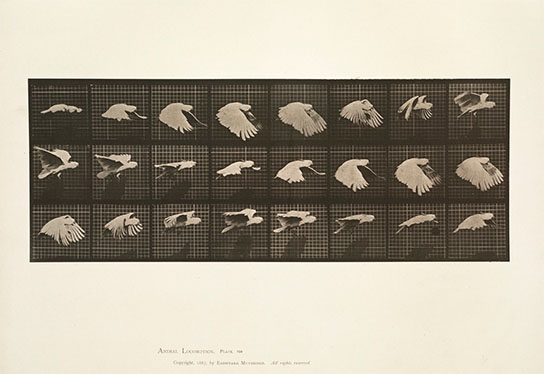

His brilliant animal studies, often overlooked in Animal Locomotion, were done using specimens from the nearby Philadelphia Zoological Gardens:

Plate 699 – Buffalo; walking

Plate 759 – Cockatoo; flying

In 1894 Muybridge retired to the home of his cousin in England. He died of a heart attack on 8 May 1904 while constructing (reportedly in the nude) a perfect scale replica of the Great Lakes in his garden. A fitting end indeed for one of the 19th century’s most eccentric geniuses.

1. The Animal Locomotion images are all from the Boston Public Library’s nearly complete copy; either the Boston Public Library’s Flickr collection or from Dave Gordon’s stunning Muybridge.org.

2. The accident killed one person and injured everyone else in the coach. Eadweard spent three days in a coma and for the next several months had double vision and a complete loss of smell and taste. After he had “recovered” his friends noticed a remarkable change in personality. He went from “genial, pleasant and quick businessman” to “eccentric, peculiar and subject to emotional outbursts.” These are now known as classic symptoms of traumatic orbitofrontal brain injury. See Shimamura, A. P. (2002). Muybridge in motion: Travels in art, psychology, and neurology. History of Photography, 26, 341-350, which is available online as a pdf.

3. This part of the story is completely awesome, so pay attention. Muybridge met the 21-yo Flora Shallcross Stone (née Downs), who was half his age, while she was working as a retoucher. After a brief affair she divorced her husband and they were married on 20 May 1871. Of course if Flora could cheat on her first husband she could certainly cheat on her second. While Muybridge was away photographing the West she began an affair with the ersatz drama critic Major Harry Larkyns.

Flora, ca.1872

Flora had a son, Floredo Helios Muybridge, on 15 Apr 1874 and later that same year Eadweard found out about the affair through her letters - the most damning of which was one with a photo of Floredo captioned “little Harry” in Flora’s handwriting. Enraged, Eadweard tracked down Larkyns at the Yellow Jacket Mine and reportedly said “I have brought a message from my wife, take it!” He shot Larkyns (with a Smith & Wesson No. 2 revolver) through the heart and killed him instantly. Muybridge offered no resistance and was immediately arrested and jailed. Flora sued for divorce on the grounds of “extreme cruelty.”

At the sensational murder trial (are there any other kind) of 2–5 Feb 1875 Eadweard’s lawyers pleaded insanity based on his stagecoach injuries. The jury, against the judge’s instructions, rejected even that defense and found him not guilty, citing “justifiable homicide.” A case of frontier justice.

To avoid the publicity, the divorce and, especially, the alimony suit, Eadweard left for Panama and Guatamela. Flora mysteriously died of Typhus on 18 Jul 1875 and Eadward, still convinced that Floredo not his son, sent him to an orphanage.

4. Muybridge, Edward J. “Improvement in the Method and Apparatus for Photographing Objects in Motion.” US patent 212864. 4 Mar 1879.

5. Muybridge, Eadweard. The Attitudes of Animals in Motion: a series of photographs illustrating the consecutive positions assumed by animals in performing various movements; executed at Palo Alto, California, in 1878 and 1879. 1881. The book, self-published by Muybridge, included 170 tipped-in albumen plates.

6. For a wonderful review of the zoopraxiscope see the Kingstons Museum’s short film Setting Time in Motion..

7. Muybridge, Eadweard. Animal Locomotion. An Electro-Photographic Investigation of Consecutive Phases of Animal Movements. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania, 1887. The work consisted of 11 volumes: Vols. 1–2: Males (nude), Vols. 3–4: Females (nude), Vol. 5: Males (pelvis cloth), Vol 6: Females & Children (semi-nude and transparent drapery), Vol. 7: Males & Females (draped) & Miscellaneous Subjects, Vol 8: Abnormal Movements Males & Females (nude and semi-nude), Vol. 9: Horses, Vol. 10: Domestic Animals and Vol. 11: Wild Animals & Birds. The copper collotype plates were prepared by the Photo-Gravure Co. of New York City and the books were printed by J.B. Lippincott of Philadelphia. Complete copies were sold for USD 500 (unbound) and USD 550 (leather).

Muybridge also offered a 100-plate subscription version where the buyer could choose plates from a list (here is the prospectus). This attenuated version, bound in “full Russia leather” was priced at USD 100 (+ 1 USD per additional plate).

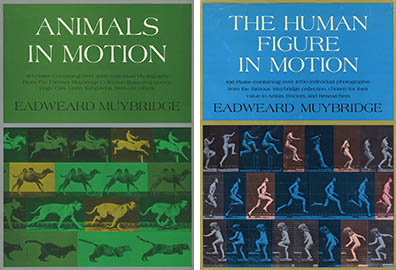

Later Muybridge reissued some of the plates in smaller, inexpensive lithographed books: Animals in Motion (London: Chapman & Hall, 1899) and The Human Figure in Motion (London: Chapman & Hall, 1901). Both titles were reissued in altered form by Dover in 1955:

8. Although Muybridge had to use artist’s models, the only women who would consent to being photographed nude, he was not especially happy about it. He said to a Philadelphia Times reporter on 2 Aug 1885; “I have experienced a great deal of difficulty in securing proper models. In the first place, artists’ models, as a rule, are ignorant and not well-bred. As a consequence, their movements are not graceful and it is essential for the thorough execution of my work to have my [female] models of a graceful bearing.”

27 Feb 2011 ‧ Photography